active galactic nucleus

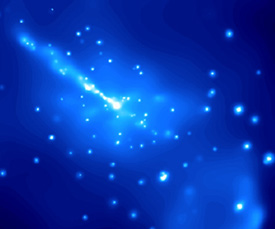

Chandra X-ray image of Centaurus A showing a bright central source: the active galactic nucleus suspected of harboring a supermassive black hole.

An active galactic nucleus (AGN) is one that gives off much more energy than can be explained purely in terms of its star content. AGN are found at the heart of active galaxies, including quasars, Seyfert galaxies, blazars, and radio galaxies. In addition to their great energy output, they can be highly variable. Some quasars vary in brightness over a few weeks or months, while some blazars show changes in X-ray output over as little as three hours. These fluctuations place strict limits on the maximum size of the energy source, because an object cannot vary in brightness faster than it takes light to travel from one side of its energy-producing region to the other. The rapid flickering of AGN means that they draw their energy from a small volume, in some cases less than one light day across. Furthermore, observations of the orbital motion of stars and other material around AGN show that a large mass, ranging up to several billion solar masses, is concentrated within its "engine room." This leads to the almost unavoidable conclusion that the central engine is a supermassive black hole. Since a black hole, by definition, emits nothing, the radiation from an AGN is believed to come from material heated to several million degrees in an accretion disk before tumbling into the black hole or, in some cases, being shot away in twin jets along the central engine's spin axis.

Unified model

Astronomers have identified a dozen or so types of AGN, each with a different overall pattern of emission. Some of these types differ only in appearance; for example, if a thick dust cloud lies between us and the center, it can block radiation at frequencies between visible light and X-rays, so that we see only the radio, infrared, and very high-energy radiation, plus the emission lines from outlying clouds.

In at least some cases, the dust in the nucleus forms a thick ring around the center. Then the appearance of the AGN depends crucially on whether it is seen side-on, so that the center is hidden, or face-on, so that the center is visible. If the line of sight is through the dust ring, the central source is obscured and the AGN would be seen as a radio galaxy. If the dust ring is tilted to our line of sight, the central source would be visible, corresponding to a quasar. If the observer is looking directly along, or close to the jet.

Radio-loud and radio-quiet

AGN fall into two major divisions: radio-loud and radio-quiet. Within each is a broad range of luminosity, from AGN so weak that they are barely detectable against the light from the central stars of their host galaxy to quasars that are more than 100 times brighter than all the stars in their hosts put together. Radio-loud AGN always produce jets in which the material may be flowing at close to the speed of light. The power of the jets (the kinetic energy flowing along them per second) roughly matches or exceeds the AGN's luminosity (total energy radiated per second). Radio-loud AGN are generally found in elliptical galaxies and almost never in spirals. Radio-quiet AGN may also have detectable jets, but these are thousands of times weaker than the AGN's total radiant energy. They usually occur in spiral galaxies, though some of the most luminous radio-quiet AGN have elliptical hosts. The obvious differences between spirals and ellipticals occur on scales many times larger than that of the AGN, and it remains uncertain how AGN "know" which type of galaxy they are in.

Low-energy AGN

In the 1980s, it became clear that nuclear activity can extend to lower levels and can appear in galaxies that superficially look normal. Many galaxies were found to show emission from their nuclei that could not be explained in detail by young stars, and these were dubbed LINERs (low-ionization nuclear emission-line regions). Debate continues as to how many kinds of objects fall into this category, but X-ray and ultraviolet observations show that some of these are indeed lower-power versions of Seyfert nuclei, complete with X-ray source and variability. The phenomenon of nuclear activity now appears to range in luminosity over six orders of magnitude and to show up in a significant fraction of bright galaxies – including our own.