extremophiles

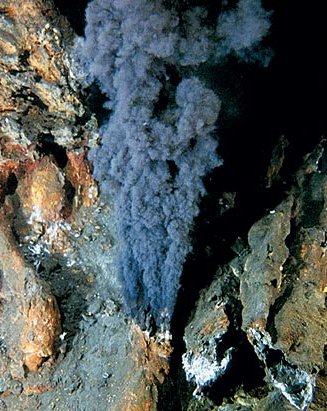

The first extremophile to have its genome sequenced was Methanococcus jannaschii, a microbe that lives near hydrothermal vents 2,600 meters below sea level, where temperatures approach the boiling point of water and the pressure is sufficient to crush an ordinary submarine. Image credit: NOAA.

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in what, for most terrestrial life-forms, are intolerably hostile environments.1 The majority of known extremophiles are varieties of archaea and bacteria. They are classified, according to the conditions in which they exist, as thermophiles, hyperthermophiles, psychrophiles, halophiles, acidophiles, alkaliphiles, barophiles, and endoliths. These categories are not mutually exclusive, so that, for example, some endoliths are also thermophiles. A polyextremophile is an organism that is tolerant to multiple extreme environments, such as high temperature and high acidity.

The discovery of extremophiles points out the extraordinary adaptability of primitive life-forms and further raises the prospect of finding at least microbial life elsewhere in the Solar System and beyond.2 There is also growing support for the idea that extremophiles were among the earliest living things on Earth (see life, origin)

Chemoautotrophs, which obtain their energy from the oxidation of inorganic chemicals, might be particularly suited to alien environments. Thiobacillus, for example, makes a living by oxidizing sulfur to sulfuric acid, while other types oxidize hydrogen to water or nitrites to nitrates. Ferrobacillus is especially interesting because the energy won from oxidizing ferrous iron to ferric is very small, so that this organism must have evolved some ingenious way of boosting its low-grade energy input to the high levels needed to make essential chemicals such as adenosine triphosphate.

Certain species can tolerate wide extremes of acidity and alkalinity. Thiobacillus will grow in solutions containing 3% sulfuric acid, while other types of bacteria have been found in the saturated brine of the Great Salt Lake in Utah and in an icy pool in Antarctica containing 33% calcium chloride.

Some bacteria have survived enormous pressures, up to 10 tons/cm2, while low pressures appear to pose no threat to them at all, providing that liquid water is present. However, although some species of bacteria, such as Deinococcus radiodurans have been found growing in the radioactive cooling ponds where fuel cans from nuclear reactors are stored, they are not tolerant of highly ionizing radiation. For this reason alone, the notion of panspermia is not easy to uphold.

| Classification and examples of extremophiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

environmental parameter |

type |

definition |

examples |

|

temperature |

hyperthermophile thermophile mesophile psychrophile |

growth >80°C growth 60-80°C 15-60°C <15°C |

Pyrolobus fumarii, 113°C Synechococcus lividis Homo sapiens Psychrobacter, some insects |

|

radiation |

Deinococcus radiodurans |

||

|

pressure |

barophile piezophile |

Weight loving Pressure loving |

unknown For microbe, 130 MPa |

|

gravity |

hypergravity hypogravity |

>1g <1g |

None known None known |

|

vacuum |

tolerates vacuum (space devoid of matter) |

tardigrades, insects, microbes, seeds |

|

|

desiccation |

xerophiles |

anhydrobiotic |

Artemia salina; nematodes, microbes, fungi, lichens |

|

salinity |

halophile |

Salt loving (2-5 M NaCl) |

Halobacteriacea, Dunaliella salina |

|

pH |

alkaliphile

acidophile |

pH >9

low pH loving |

Natronobacterium, Bacillus firmus OF4, Spirulina spp. (all pH 10.5) Cyanidium caldarium, Ferroplasma sp. (both pH 0) |

|

oxygen tension |

anaerobe microaerophil aerobe |

cannot tolerate O2 tolerates some O2 requires O2 |

Methanococcus jannaschii Clostridium Homo sapiens |

|

chemical extremes |

gases metals |

Can tolerate high concentrations of metal (metalotolerant) |

Cyanidium caldarium (pure CO2) Ferroplasma acidarmanus(Cu, As, Cd, Zn); Ralstonia sp. CH34 (Zn, Co, Cd, Hg, Pb) |

References

1. Gross, Michael. Life on the Edge: Amazing Creatures Thriving in

Extreme Environments. New YorK: Plenum (1998).

2. Seckbach, J. "Search for Life in the Universe with Terrestrial Microbes

Which Thrive Under Extreme Conditions." In Cristiano Batalli Cosmovici,

Stuart Bowyer, and Dan Wertheimer, eds., Astronomical and Biochemical

Origins and the Search for Life in the Universe, p. 511. Milan:

Editrice Compositori (1997).