Harvey, William (1578–1657)

The discovery of the circulation of the blood was published by Harvey in his book De Motu Cordis, in 1628. Harvey is shown in Hannah's painting demonstrating the principle to Charles I.

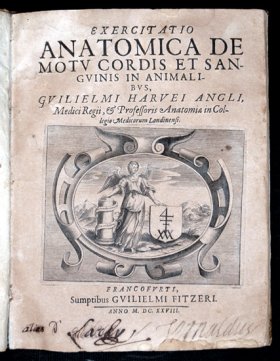

Title page of Harvey's Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus. Credit: Indiana University.

William Harvey was an English physician and anatomist who discovered the circulation of blood. This landmark in medical history marked the beginning of modern physiology. His findings, published in 1628, were ridiculed at first and only later generally accepted. Harvey also carried out important studies in embryology.

width="280">

|

His career

William Harvey was born in Folkestone, a town on the south coast of England. He was educated at Canterbury Grammar School and at Caius College, Cambridge, where he obtained his BA, then went to Padua, Italy, to study medicine. His coat of arms is still displayed in the entrance hall of the University of Padua, a tribute to one of that institution's greatest pupils. In 1607 he was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians in London, and two years later was appointed to the post of physician to St. Bartholomew's Hospital.

In 1616 Harvey began a course of lectures in which he first expressed his views on the movements of the heart and of the blood contained in it and in the arteries and veins. It was not until 1628, however, that he published the work which made him famous: the Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus. The whole was in Latin, as was custom at that time. Translated, the title is: "Anatomical treatise on the motion of the heart and blood in animals".

Harvey was a man of great energy and ability and the leading physician of his day. He was physician by royal appointment to two English kings, James I and Charles I, and he attended the ill-fated Charles at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642. In 1651, towards the end of his life, he published another work, Exercitationes de generatione (Studies on reproduction). Although longer than the treatise on circulation it is not regarded of equal importance as a contribution to science, though it is a record of an immense amount of detailed observation.

Harvey's ideas on blood circulation

Until the 16th century ideas about the movements of the blood in the living body were extremely vague. It was known that the blood was not stagnant, but it was supposed to ebb and flow in the veins and arteries, preserving no particular direction. The prevailing theories were based on those of the Greek physician Galen, who lived in the 2nd century AD. Some advance was made shortly before Harvey's time, mainly in Italy.

Harvey's teacher at Padua, Fabricius of Aquapendente, demonstrated the presence of valves in the veins, which seemed to indicate that the blood must flow in one direction. It was also recognized that blood must circulate in the body, but it remained for Harvey to explain fully the mechanism by which it does so.

The heart is divided into four chambers: a right and left atrium and a right and a left ventricle. The ventricles are thick-walled and muscular and each one is connected by an opening with the atrium on its own side but is divided from its fellow ventricle by a wall or septum; the two atria are similarly divided from each other. Blood enters the atria by veins and is pumped out of the ventricles through arteries. Having circulated in the body, blood enters the right atrium and then passes into the right ventricle, which contracts and forces it along an artery to the lungs. There it receives oxygen and returns by a vein to the left atrium, passes into the left ventricle and is pumped into a large artery from which it circulates in the body. Having lost its oxygen it comes back to the right atrium and goes all the way around again.

It was this mechanism which was expounded by Harvey in his treatise, and it was a thing wholly new to the science of medicine and anatomy. In his researches on the subject he carried out many dissections of dead and living animals, including dogs, pigs, and even such creatures as lobsters, shrimp, and slugs. Of course, he made human dissections as well.

In one respect his work was incomplete: he failed to show how the blood in the body passes from the arterial system back to the venous system. It was the Italian anatomist Marcello Malpighi who, by his discovery of the capillary blood vessels, cleared this point up only four years after Harvey's death.