International Space Station

The International Space Station photographed from the space shuttle Endeavour during its mission to the orbiting outpost in July 2009. The combined shuttle and ISS crews set a new record of 13 people on the station.

The ISS photographed from the shuttle Discovery in 2006.

ISS configuration as of December 2007.

Current configuration of ISS.

Size comparison of the ISS and a Boeing 747.

Size comparison of the ISS and a football field.

Zarya (top) and Unity – the first two ISS modules.

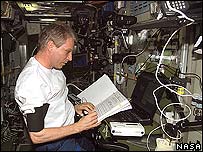

ESA astronaut Thomas Reiter performs cardiovascular and cognitive studies in Zvezda.

Inside the Destiny lab.

The International Space Station (ISS) is the largest space station ever built, the largest structure ever assembled in space, and one of the most complex international scientific projects in history. Now essentially complete, the ISS is more than four times larger than the old Soviet Mir space station and longer than an American football field (including the end-zones). It has a pressurized living and working space approximately equivalent to the volume of a 747 jumbo-jet or a conventional five-bedroom house, and can accommodate up to seven astronauts. It has a gymnasium, two bathrooms, and a bay window. The solar panels, spanning more than half an acre, supply 84 kilowatts – 60 times more electrical power than that available to Mir. The ISS has been continuously occupied since 2 November 2000, and is visible, at times, in the night sky to the naked eye. It will continue in operation until at least 2015, and possibly as late as 2020.

The orbit of ISS, with a perigee of 278 kilometers (173 miles), apogee of 460 kilometers (286 miles), and inclination of 51.6°, allows the station to be reached by the launch vehicles of all the international partners for delivery of crews, components, and supplies. The orbit also enables observations to be made of 85% of the globe and over-flight of 95% of Earth's population.

The ISS has 15 pressurized modules, including laboratories, living quarters,

docking compartments, airlocks, and nodes.

| ISS statistics | |

|---|---|

| mass | 390,908 kg (861,804 lb) |

| length (from PMA-2 to Zvezda) | 73 m (240 ft) |

| width (along truss, arrays extended) | 108.5 m (356 ft) |

| height (nadir–zenith, arrays forward–aft) | 20 m (66 ft) |

| habitable volume | 388 m3 (13,696 ft3) |

History

In 1984 President Ronald Reagan committed the United States to developing a permanently-occupied space station and, along with NASA, invited other countries to join the project. Within little more than a year, nine of ESA's 13 member countries had signed on, as had Canada and Japan.

In 1991 President George Bush (senior) and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to joint Space Shuttle-Mir missions that would lay the groundwork for cooperative space station efforts. From 1993 to the present, NASA has had to contend with numerous cost overruns and tight federal space budgets, plus the tragic loss in 2003 of the Space Shuttle Columbia that have eroded the station's capabilities and delayed its completion. Nevertheless, by streamlining the program, simplifying the station's design, and negotiating barter and cost-sharing agreements with other nations, NASA and its international partners have made the ISS a reality.

On-orbit assembly of the station began on 20 November 1998, with the launch of the Russian-built Zarya control module, and is due for completion in 2010.

International contributions

Although the United States, through NASA, leads the ISS project, 15 other countries are involved in building and operating various parts of the station – Russia, Canada, Japan, Brazil, and 11 member nations of ESA (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Contributions include:

United States

- truss structures that provide the ISS framework

- four pairs of large solar arrays

- three nodes with ports for spacecraft and for passage to other ISS

elements

- airlock that accommodates American

and Russian spacesuits

- the American laboratory (Destiny)

- habitation and centrifuge accommodation modules

- power, communications and data services

- thermal control, environmental control and life support health

Russia

- two research modules

- service module with its own life support and habitation systems

- science power platform that supplies about 20 kW of electrical

power

- logistics transport using Progress vehicles and Soyuz spacecraft crew

rotation

ESA

- Columbus Orbital Facility (pressurized laboratory and external payload

accommodations)

- logistics transport vehicles to be launched by the Ariane V

Canada

- Mobile Servicing System (17-meter-long robotic arm and with a smaller

manipulator attachment

- a Mobile Remote Servicer Base to allow the robotic arm to travel along

the truss

Japan

- on-orbit Kibo facility (pressurized laboratory, Logistics Module,

and attached facility exposed to the vacuum of space serviced by a robotic

arm

- logistics resupply using the H-2 launch vehicle

Brazil

- a pallet to house external payloads, unpressurized logistics carriers,

and an Earth observation facility

ISS components (in order of assembly)

Zarya ("Dawn") Module

A 19,300-kilogram (42,250-pound), 12.6-meter (41-foot) long, 4.1-meter (13-foot) wide module, equipped with solar arrays and six nickel-cadmium batteries capable of generating an average of 3 kilowatts of power, that provided early propulsion, power, fuel storage, and communication, and served as the rendezvous and docking port for Zvezda.

Zarya's construction was funded by NASA and undertaken in Moscow by Boeing and the Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Center. Following its launch, it was put through a series of tests before being commanded to fire its two large engines to climb to a circular orbit 386 kilometers high. The module's engines and 36 steering jets had a six-ton reservoir of propellant to enable altitude and orientation changes. Its side docking ports are used by Russia's Soyuz piloted spacecraft and Progress remotely-controlled supply vehicles. As assembly progressed, Zarya's roles were assumed by other Station elements and it is now used primarily as a passageway, docking port and fuel storage site.

Unity Node 1

The Unity Node is a connecting passageway to living and work areas of the ISS. It was the first major US-built component of the station. Unity Node was delivered during STS-88 on Space Shuttle Endeavour in December 1998. The Pressurized Mating Adapter 1 was prefitted to its aft port. The crews conducted three space walks to attach Pressurized Mating Adapter 1 to the Zarya Control Module. This was the second International Space Station Assembly Flight and was designated 2A.

In addition to its connection to Zarya, Unity serves as a passageway to the U.S. Laboratory Module and an airlock. It has six hatches that serve as docking ports for the other modules.

Unity Node 1 is 5.5 meters (18 feet) long, 4.6 meters (15 feet) in diameter, and fabricated of aluminum. It contains more than 50,000 mechanical items, 216 lines to carry fluids and gases, and 121 internal and external electrical cables using 9.7 kilometers (6 miles) of wire.

Zvezda Service Module

The first fully Russian contribution to the ISS and the early cornerstone for human habitation of the station. The 19-ton, 13.1-meter-long Zvezda, provided the first living quarters aboard the station, together with electrical power distribution, data processing, flight control, and propulsion systems. It also has a communications system enabling remote command from ground controllers. Although many of its systems will eventually be supplemented or superceded by American components, Zvezda will remain the structural and functional center of the Russian segment of the ISS.

Integrated Truss Structure

An American-supplied framework that serves as the backbone of the ISS and the mounting platform for most of the station's solar arrays. The truss also supports a mobile transporter that can be positioned for robotic assembly and maintenance operations and is the site of the Canadian Mobile Servicing System, a 16.8-meter-long robot arm with 125-ton payload capability and mobile transporter which can be positioned along the truss for robotic assembly and maintenance operations.

Destiny Laboratory

America's main workstation for carrying out experiments aboard the ISS. The 16.7-meter-long, 4.3-meter-wide, 14.5-ton Destiny will support research in life sciences, microgravity, Earth resources, and space science. It consists of three cylindrical sections and two end-cones. Each end-cone contains a hatch through which crew members will enter and exit the lab. There are 24 racks inside the module, 13 dedicated to various experiments, including the Gravitational Biology Facility, and 11 used to supply power, cool water, and provide environmental control.

Multi-Purpose Logistics Modules

Effectively the ISS's moving van. Built by the Italian Space Agency it allows the Space Shuttle to ferry experiments, supplies, and cargo back and forth during missions to the station.

Prelude to ISS: the Shuttle-Mir program

Between 1995 and 1998, nine Space Shuttle-Mir docking missions were flown and American astronauts stayed aboard Mir for lengthy periods. Nine Russian cosmonauts rode on the Shuttle and seven American astronauts spent a total of 32 months aboard Mir, with 28 months of continuous occupancy starting in March 1996. By contrast, it took the Shuttle fleet more than a dozen years and 60 flights to accumulate one year in orbit. Valuable experience was gained in training international crews, running an international space program, and meeting the challenges of long-duration spaceflight for mixed-nation astronauts and ground controllers. Dealing with the real-time challenges of the Shuttle-Mir missions also fostered in a new level of cooperation and trust between those working on the American and Russian space programs.

The ISS takes shape

Construction of the ISS began in late 1998 and was originally projected to involve a total of 45 assembly missions, including 36 by the Shuttle, and numerous re-supply missions by unmanned Progress craft and rotations of Soyuz crew-return vehicles.

| Early ISS missions | |

|---|---|

| Launch date | Description |

| Nov. 20, 1998 | A Proton rocket places the Zarya module in orbit |

| Dec. 4, 1998 | Shuttle mission STS-88 attaches the Unity module to Zarya |

| May 27, 1999 | STS-96 delivers tools and cranes to the two modules |

| May 19, 2000 | STS-101 conducts maintenance and delivers supplies in preparation for arrival of Zvezda and the station's first permanent crew |

| Jul. 12, 2000 | A Proton rocket delivers Zvezda |

| Sep. 8, 2000 | STS-106 delivers supplies and outfits Zvezda |

| Oct. 11, 2000 | STS-92 delivers the Z1 Truss, a pressurized mating adapter for Unity, and four gyros |

| Nov. 2000 | Arrival of Expedition One crew aboard a Soyuz spacecraft |

| Nov. 30, 2000 | STS-97 installs the first set of American solar arrays |

| Feb. 7, 2001 | STS-98 delivers the Destiny laboratory module and relocates a pressurized mating adapter from the end of Unity to the end of Destiny |

| Mar. 8, 2001 | STS-102 brings Expedition Two crew plus equipment for Destiny and returns with Expedition One crew |

| Apr. 19, 2001 | STS-100 delivers Remote Manipulator System and more laboratory equipment |

| Jul. 12, 2001 | STS-104 delivers the station's joint airlock |

| Aug. 2001 | Arrival of the Expedition Three crew and return of Expedition Two |

| Sep. 2001 | Delivery of the Russian docking compartment by a

Soyuz rocket |

| ISS expeditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expedition | Period (between undockings) | Commander | Flight engineers |

| 1 | Nov 2, 2000– Mar 18, 2001 |

William Shepherd | Yuri Gidzenko, Sergei Krikalev |

| 2 | Mar 18, 2001– Aug 20, 2001 |

Yuri Usachev | Susan Helms, Jim Voss |

| 3 | Aug 20, 2001– Dec 15, 2001 |

Frank Culbertson |

Vladimir Dezhurov, Mikhail Tyurin |

| 4 | Dec 15, 2001– Jun 15, 2002 |

Yury Onufrienko |

Dan Bursch, Carl Walz |

| 5 | Jun 15, 2002– Dec 2, 2002 |

Valery Korzun |

Sergei Treschev, Peggy Whitson |

| 6 | Dec 2, 2002– May 3, 2003 |

Ken Bowersox |

Nikolai Budarin, Don Petitt |

| 7 | May 3, 2003– Oct 23, 2003 |

Yuri Malenchenko |

Ed Lu |

| 8 | Oct 23, 2003– Apr 29, 2004 |

Michael Foale |

Alexander Kaleri |

| 9 | Apr 29, 2004– Oct 23, 2004 |

Gennady Padalka |

Mike Fincke |

| 10 | Oct 23, 2004– Apr 24, 2005 |

Leroy Chiao |

Salizhan Sharipov |

| 11 | Apr 24, 2005– Oct 10, 2005 |

Sergei Krikalev |

John Phillips |

| 12 | Oct 10, 2005– Apr 8, 2006 |

William McArthur |

Valery Tokarev |

| 13 | Apr 8, 2006– Sep 28, 2006 |

Pavel Vinogradov |

Thomas Reiter, Jeffrey Williams |

| 14 | Sep 28, 2006– Apr 21, 2007 |

Michael Lopez-Alegria |

Sunita Williams, Mikhail Tyurin |

| 15 | Apr 21, 2007– Oct 21, 2007 |

Fyodor Yurchikhin |

Clayton Anderson, Oleg Kotov |

| 16 | Oct 21, 2007– Apr 19, 2008 |

Peggy A. Whitson |

Yuri Malenchenko, Daniel M. Tani |

| 17 | Apr 19, 2008– Oct 23, 2008 |

Sergei Volkov |

Oleg Kononenko, Garrett Reisman, Gregory Chamitoff |

| 18 | Oct 23, 2008– Mar 28, 2009 |

Michael Fincke |

Gregory Chamitoff, Yury Lonchakov, Sandra Magnus, Koichi Wakata |

| 19 | Mar 28, 2009– May 29, 2009 |

Gennady Padalka |

Michael Barratt, Koichi Wakata |

| 20 | May 29, 2009– Oct 10, 2009 |

Gennady Padalka |

Frank De Winne, Roman Romanenko, Robert Thirsk, Michael Barratt, Nicole Stott, Tim Kopra, Koichi Wakata |

| 21 | Oct 10, 2009– Nov 30, 2009 |

Jeffrey Williams |

Frank De Winne, Roman Romanenko, Robert Thirsk, Nicole Stott, Maxim Suraev, Guy Laliberté |

| 22 | Nov 30, 2009– Mar 18, 2010 |

Jeffrey Williams |

Oleg Kotov, Timothy Creamer, Maxim Suraev, Soichi Noguchi |

| 23 | Mar 18, 2010– Jun 1, 2010 |

Oleg Kotov |

Timothy Creamer, Soichi Noguchi, Mikhail Kornienko, Tracy Caldwell Dyson, Alexander Skvortsov |

| 24 | Jun 1, 2010– Sep 25, 2010 |

Alexander Skvortsov |

Tracy Caldwell Dyson, Mikhail Kornienko, Shannon Walker, Douglas Wheelock, Fyodor Yurchikhin |

| 25 | Sep 25, 2010– Nov 26, 2010 |

Douglas Wheelock |

Fyodor Yurchikhin, Shannon Walker, Scott Kelly, Alexander Kaleri, Oleg Skripochka |

| 26 | Nov 26, 2010– Mar 16, 2010 |

Scott Kelly |

Alexander Kaleri, Oleg Skripochka, Catherine Coleman, Dmitry Kondratyev, Paolo Nespoli |

| 27 | Mar 16, 2011– May 23, 2011 |

Dmitri Kondratyev |

Catherine Coleman, Paolo Nespoli, Andrei Borisenko, Aleksandr Samokutyayev, Ron Garan |

| 28 | May 23, 2011– Sep 16, 2011 |

Andrey Borisenko |

Ron Garan, Alexander Samokutyaev, Sergei Volkov, Mike Fossum, Satoshi Furukawa |

| 29 | Sep 16, 2011– Nov 21, 2011 |

Mike Fossum |

Satoshi Furukawa, Sergei Volkov, Anton Shkaplerov, Anatoli Ivanishin, Dan Burbank |

| 30 | Nov 21, 2011– Apr 27, 2012 |

Dan Burbank |

Anton Shkaplerov, Anatoli Ivanishin, Oleg Kononenko, André Kuipers, Don Pettit |

| 31 | Apr 27, 2012– Jul 1, 2012 |

Oleg Kononenko |

André Kuipers, Don Pettit, Joseph M. Acaba, Gennady Padalka, Sergei Revin |

| 32 | Jul 1, 2012– |

Gennady Padalka |

Joseph M. Acaba, Sergei Revin, Sunita Williams, Yuri Malenchenko, Akihiko Hoshide |