moons of Mars

Fig 1. Phobos (top) and Deimos (bottom).

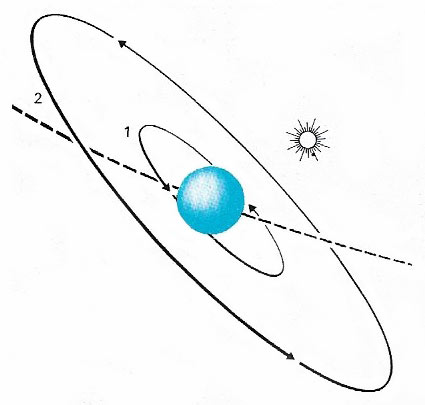

Fig 2. Both the satellites of Mars move in orbits that are practically circular and in the plane of the planet's equator. Phobos (1) is remarkably close to Mars and may approach to within 5,800 kilometers (3,600 miles). It is the only known natural satellite with a revolution period shorter than the rotation of its primary, and as seen from the planet it rises in the west and sets in the east. Deimos (2) is much further out, with a period of 30 hours 14 minutes.

There had been early (groundless) speculation about the existence of two martian satellites (see Swift, Jonathan and the moons of Mars) but it was not until 1877 that diminutive Phobos and Deimos were discovered by Asaph Hall at the US Naval Observatory.1 Working at the same site, Bevan Sharpless concluded in 1944, after analyzing measurements made since Hall's discovery, that the orbit of Phobos was decaying.2 Rapidly, his data suggested, the little moon was spiraling on a collision course with Mars.

For a number of years, this result remained a minor curiosity. Then, in 1959, Soviet astrophysicist Iosef Shklovskii took up the challenge to explain why the orbit of Phobos was shrinking. He looked at the possibility that the thin upper regions of the martian atmosphere might be gradually slowing Phobos down, but decided this effect would be too small to account for the results Sharpless had obtained. Among the alternatives he considered were the influence of the Sun, a tidal interaction with the gravity of Mars, and the effect of a hypothetical martian magnetic field. However, none of these seemed able to provide a satisfactory mechanism. So Shklovskii went back to the idea that atmospheric drag might somehow be involved and came up with an audacious suggestion. What, he asked, if Phobos were not an ordinary moon? What if its average density were only a thousandth that of water, so that the thin outer atmosphere of Mars could act as an effective brake and destabilize the little moon's orbit? What, in fact, if Phobos were hollow? A hollow object 24 kilometers (15 miles) across could not possibly be natural. It would have to be the product of a technology well in advance of our own, surpassing even that required to build the great network of waterways and pumping stations envisaged by Lowell. In Intelligent Life in the Universe, coauthored with Carl Sagan, Shklovskii writes:3

Since Mars does not have a large natural satellite such as our moon, the construction of large, artificial satellites would be of relatively greater importance to an advanced martian civilization in its expansion into space... The launching of massive satellites from Mars would be a somewhat easier task than from Earth, because of the lower martian gravity.

Shklovskii thought it unlikely that the creators of Phobos were still alive:

Perhaps Phobos was launched into orbit in the heyday of a technical civilization on Mars, some hundreds of millions of years ago.

But the idea of advanced extant martian life did not seem beyond belief to some others, including Frank Salisbury, Professor of Plant Physiology at Colorado State University. He pointed out that neither of the martian moons had been spotted in 1862, when Mars was closer than in Hall's discovery year of 1877 and when large instruments were trained upon it:

Should we attribute the failure of 1862 to imperfections in the existing telescopes, or may we imagine that the satellites were launched into orbit between 1862 and 1877?

Sadly, close-up photographs of Phobos taken by the Viking orbiters and other probes, have revealed a more prosaic truth. There is nothing suggestive of artifice about this rocky, pock-marked, potato-shaped moon. In all likelihood it was once, like Deimos, an asteroid which, during its solar peregrinations, strayed too far into the gravitational domain of Mars and became ensnared. Measurements made during the favorable opposition of Mars in 1988 confirmed that the orbit of Phobos is unstable. However, its rate of decay is only about half that claimed by Sharpless so that it can be accounted for in terms of frictional forces acting on a natural, solid body. Each year the little moon draws 2.5 centimeters closer to its parent planet. Phobos never came from the surface Mars. But it will eventually end up there, blasting a crater roughly 500 kilometers (300 miles) across some time within the next 40 million years.

References

1. Gingerich, O. "The Satellites of Mars: Prediction and Discovery," Journal of the History of Astronomy, 1, 109 (1970).

2. Sharpless, B. P. "Secular Accelerations in the Longitudes of the Satellites

of Mars," Astronomical Journal, 51, 185 (1945).

3. Shklovskii, I. S., and Sagan, Carl. Intelligent Life in the Universe.

New York: Dell (1966).