Moon base

NASA 1993 LUNOX concept for a lunar habitat assembled out of components delivered by automated cargo flights. Pressurized rovers, logistics modules, and a spacesuit maintenance and storage module combine to provide the living and working quarters for the crew.

Shackleton Crater - a possible future Moon base location.

NASA announced in December 2006 its intention to begin building a permanent base on the Moon by 2020. Crews and materials would have been launched from Earth by Ares V rockets and traveled to the Moon aboard Orion spacecraft and automated transport vehicles.

The base would probably have been set up near to one of the Moon's poles because such a location would afford moderate temperatures, a high percentage of sunlight for supplying solar power, and more opportunities for launches. There is also the possibility that some deep craters in the polar regions may harbor ice, which could be tapped as a water supply.

In the event, NASA's ambitious plans were not matched by the greatly increased government funding needed to make them become a reality. Many schemes for human outposts on our closest celestial neighbor have been aired over the past few decades but have failed to progress beyond the printed word. It remains to be seen if a lunar base will ever actually be built.

History

The idea of a colony on the Moon has long been a favorite of science fiction writers and space visionaries. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky described such a base, as did others as long ago as the late 19th and early twentieth centuries. From the 1950s onward, a number of quite detailed concepts and designs have been suggested by scientists, engineers, and science writers.

|

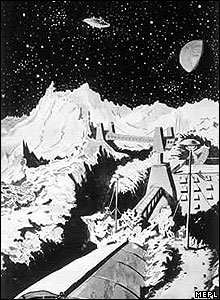

| Sketch from 1895 of a gold mine in operation on the

Moon

|

|

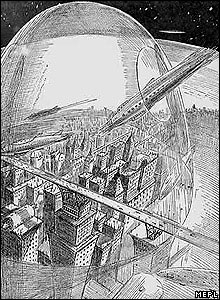

| A 1934 illustration for The Moon Pirates,

a sci-fi novel by Neil R Jones, depicting a city on the Moon enclosed

by a protective dome

|

In 1954, Arthur C. Clarke proposed a lunar base made of inflatable modules and covered in lunar dust for insulation. A spaceship, assembled in low Earth orbit, would be launched towards the Moon and land on Mare Imbrium, near Mons Piton. Astronauts would then set up igloo-like modules and an inflatable radio mast. Subsequent steps would include the establishment of a larger, permanent dome, an algae-based air purifier, a nuclear reactor to supply power, and electromagnetic cannons, also known as mass drivers, to launch cargo and fuel to interplanetary vessels in space.

In 1958, the US Air Force began a study called Lunex (Lunar Expedition) with the goal of putting a military base on the Moon by 1968. The following year, the U.S. Army went through a similar exercise, known as Project Horizon, with the aim of establishing a military presence on the Moon by 1967. Project Horizon was led by H. H. Koelle, a German rocket engineer of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. The first landing would have been carried out by two "soldier-astronauts" in 1965. More construction workers would soon have followed and, through numerous launches (61 Saturn I and 88 Saturn V), 245 tons of cargo would have been transported to the outpost by 1966.

Various schemes for lunar bases have been explored by other nations, most notably the Soviet Union and China. And before the cancellation of the Apollo Project there were also plans to extend Apollo into the era of human habitation on the Moon. This would have been the ideal time for such a segue, but the political will and public interest to support such a venture had waned and funding for Apollo dried up.

In the decades, that followed the first Moon landing, various presidents announced their intention of revitalizing efforts to colonize the Moon. However, these proved to be little more than public rhetoric. Most recently, in 2004, President George Bush, Jr, called on NASA to "gain a new foothold on the Moon and to prepare for new journeys to the worlds beyond our own," including a return to the Moon by 2020. This led to the scheme for a lunar base announced in 2006.

|

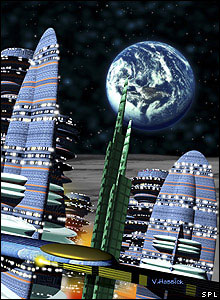

| Contemporary vision of lunar city, each building

with its own protective seal

|

Moon base 2020

NASA scientists favored siting a solar-powered Moon base near one of the lunar poles, a location such as Shackleton Crater near the South Pole. Plans called for a first post-Apollo landing by 2020, with 30-day residential missions by 2024, increasing to six months by the end of that year.

The space agency pointed to six key aims for lunar exploration:

• Extend human presence to the Moon to enable eventual settlement.

• Pursue scientific activities that address fundamental questions about the history of Earth, the Solar System and the Universe.

• Test technologies, systems, flight operations and exploration techniques to reduce the risks and increase the productivity of future missions to Mars and beyond.

• Provide a challenging, shared and peaceful activity that unites nations in pursuit of common objectives.

• Expand Earth's economic sphere, and conduct lunar activities with benefits to life on the home planet.

• Use a vibrant space exploration program to engage the public, encourage students and help develop the high-tech workforce that will be required to address the challenges of tomorrow.

By 2025, NASA hoped to have developed the capabilities required to enable further steps into space, possibly expanding lunar exploration and/or manned missions to Mars.