Stardust

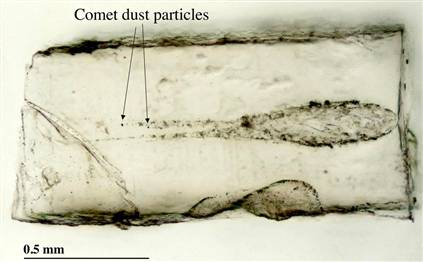

A tiny bit of aerogel contains a carrot-shaped track carved by comet dust particles, as seen in this cross-section. The particles themselves are at the very tips of the "carrot." Image: NASA.

Stardust is a spacecraft launched on 7 February 1999, with the object of encountering comet Wild-2 in January 2004 and returning samples of it to Earth. Stardust made three loops around the Sun. On the second loop, it passed within 260 km of the nucleus of Wild-2, sent back pictures, took counts of the number of comet particles striking it, and analyzed in real-time the composition of substances in the comet's tail. It also captured samples of cometary material using a sponge-like cushioning substance called aerogel that is attached to panels on the spacecraft. Additionally, Stardust obtained samples of cosmic dust, including the recently discovered interstellar dust streaming into the solar system from the direction of Sagittarius. Having been "soft-caught" and preserved by the aerogel, these samples were brought back to Earth by a reentry capsule which landed in Utah at 1012 GMT on on 15 January 2006. Analysis of the material from Wild-2 and interstellar space, which is expected to include presolar grains and condensates left over from the formation of the solar system, will yield important insights into the evolution of the Sun and planets and possibly the origin of life itself.

|

| Stardust approaches Comet Wild

|

|

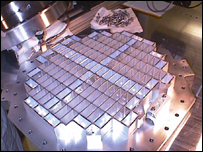

| Stardust collector trays filled with

aerogel

|

|

| Recovery of the Stardust capsule

|

Having accomplished its primary objective, Stardust was redirected to a successful encounter with comet Tempel 1 on February 14, 2011, with the purpose of examining the crater formed several years earlier on the comet's nucleus by the impactor carried by the Deep Impact probe.

Stardust is the fourth mission in NASA's Discovery Program, following Mars Pathfinder, the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) probe, and Lunar Prospector. It represents an international collaboration between NASA and university and industry partners.

Return of Stardust

After a seven-year, 4.6-billion-kilometer (2.8-billion-mile) journey, the Stardust released its 45-kilogram (110-pound) sample-return capsule at 0557 GMT, 15 January 2006, as it looped past the Earth. Four hours after leaving the probe, the capsule entered Earth's atmosphere 125 kilometers (410,000 feet) over the Pacific Ocean at a speed of 46,660 kilometers per hour (29,000 mph) – the fastest Earth atmosphere reentry of any spacecraft. At an altitude of about 32 kilometers (105,000 feet), the capsule released a drogue parachute to slow its descent. The main parachute opened at about 3 kilometers (10,000 feet), and brought the capsule down to land on a military base southwest of Salt Lake City.

The capsule was located by helicopter almost an hour after the landing and then flown to a nearby laboratory for checks. On 16 January, it was transported to a special lab at NASA's Johnson Space Center for examination of its precious extraterrestrial cargo.

Preliminary scientific findings

Initial results from analysis of Stardust's aerogel suggest that the particles of captured comet dust contain iron sulfides, glassy material such as crystalline silicates, and an assortment of organic materials. Researchers will want to know which of these organics are genuinely extraterrestrial and which are the result of contamination here on Earth. In the weeks and months ahead, work will be done to analyze the types of carbon found in the samples – not only to trace the organics, but also to determine whether such compounds predated the formation of the solar system.

Stardust@home

A project similar to SETI@home has been set up so that members of the public can use their PCs to help analyze the material brought back by Stardust. Images of the aerogel from the spacecraft will be produced by scanning under ultraviolet light using an automated microscope at a clean room at JSC. More than 1.6 fields of view will be produced and made available for study by people who have registered go through a web-based training session to see if they are suitable for spotting particles in the aerogel. To take part, volunteers need a reasonably up-to-date computer with Netscape or Internet Explorer, patience, and some spare time.

Once located, the particles will be extracted from the gel and analyzed in research labs around the world. As well as the satisfaction of taking part in the space project, volunteers have another incentive – the chance to name any dust grains they find.