Sun

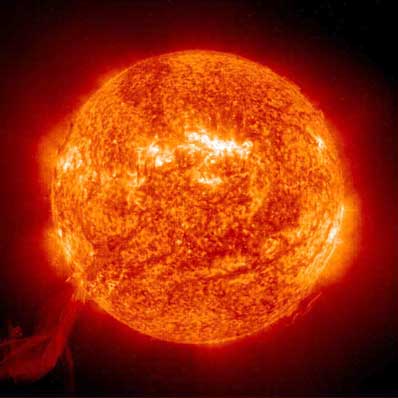

Figure 1. An image of the Sun taken by the SOHO spacecraft, showing a large solar flare to the bottom left.

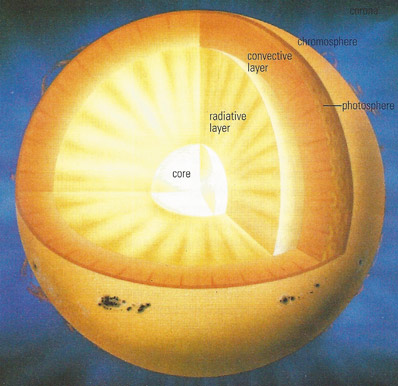

Figure 2. Cross-section of the Sun, showing the core, radiative layer, convective layer, photosphere, chromosphere, and corona.

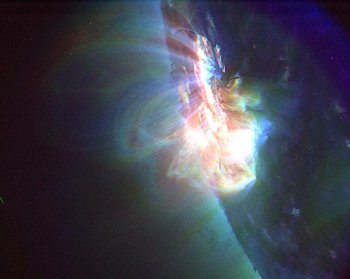

Figure 3. An active region of the Sun. Credit: A. Title (Stanford Lockheed Institute), TRACE, NASA.

The Sun is the star around which Earth revolves, and the gravitational center of the Solar System. It lies about 270,000 times closer to us than the next nearest star. The Sun is a solitary, yellow dwarf star of spectral type G2 (see G star) that has been on the main sequence for about 4.6 billion years.

The Sun consists largely of hydrogen (71% by mass) and helium (27%), with much smaller amounts of heavier elements. It puts out 400 trillion trillion watts of energy, produced by the fusion of hydrogen to helium by the carbon-nitrogen cycle in its core. The Sun is 109 times wider than Earth. It spins on its axis with a period that varies from 25 days at the equator to 33.5 days near the poles.

The mass of the Sun is approximately 2,000 trillion trillion tons or 2 × 1030 kilograms. This is known as a solar mass and is a commonly used unit in astronomy and astrophysics.

The visible surface, or photosphere, is surrounded by the chromosphere and, beyond this, the corona. An active region (Figure 3) is a localized volume of the Sun's outer atmosphere where powerful magnetic fields, emerging from subsurface layers, give rise to various short-lived features. These features may include:

In the photosphere:

In the chromosphere:

In the corona:

Solar cycle

The Sun exhibits an approximately 11-year quasi-periodic variation in frequency or number of solar active events, called the solar cycle. The month(s) during the solar cycle when the 12-month mean of monthly average sunspot numbers reaches a maximum is known as solar maximum. On the other hand, the quiet sun is when the Sun when the solar cycle of activity is at a minimum. Typically during such times there is less than one chromospheric event (a mild solar flare) per day.

International Quiet Sun Years

The International Quiet Sun Years (IQSY) was a period from 1 January 1964 to 31 December 1965, near solar minimum, when solar and geophysical phenomena were studied by observatories around the world and by spacecraft to improve our understanding of solar-terrestrial relations.

Solar radio emission

The Sun emits radio wavelengths from centimeters to decameters, under both quiet and disturbed conditions, of which several types are recognized. Type I is a noise storm composed of many short, narrowband bursts in the metric range (50 to 300 mehahertz). Type II is narrowband emission that begins in the meter range (300 MHz) and sweeps slowly (over tens of minutes) toward decameter wavelengths (10 MHz). Type II emissions occur in loose association with major flares and are indicative of a shock wave moving through the solar atmosphere. Type III are narrowband bursts that sweep rapidly (in a matter of seconds) from decimeter to decameter wavelengths (0.5 to 500 MHz). This type often occurs in groups and is an occasional feature of complex solar active region. Type IV is a smooth continuum of broadband bursts primarily in the meter range (30–300 MHz). These bursts are associated with some major flare events beginning 10 to 20 minutes after the flare maximum, and can last for hours.

An almost-perfect sphere

In 2012, a team of scientists led by Jeffrey Kuhn, of the University of Hawaii, announced the first most precise measurement ever made of the Sun's oblateness – the extent to which it bulges out at the equator.1 Surprisingly, it turns out, the Sun is an almost perfect sphere. Despite being 1.4 million kilometers across, its equatorial diameter is a mere 10 kilomeers more than its diameter from pole to pole. If the Sun were scaled down to the size of a beach ball, the difference between its equatorial and polar diameters would be less than the width of a human hair. Given that the Sun spins on it axis, once every 28 days, and is made of (ionized) gas, this result implies that effects, such as magnetism or turbulence, play a greater effect in determining the overall shape of the Sun than had been expected.

Sun-like stars and solar stability

Since the Sun is unique in having a known (to humans!) habitable planet, it is natural that scientists first turn to stars similar to the Sun in their search for extraterrestrial life. Superficially, there are many such stars, including a handful that are less than 20 light-years away (see Sunlike stars). During this decade and beyond, attention will be focused on trying to detect Earthlike planets orbiting within the habitable zones of such solar look-alikes. However, it may be that in at least one respect the Sun is abnormal. A consensus is emerging that our star is exceptionally stable. Although like all stars it sends out flares from time to time, these tend to be on a very modest scale by stellar norms. What is still unknown is why the Sun is so well-behaved, and whether we just happen to be enjoying a tranquil phase in its career.

| distance | 149,597,900 km (92,975,699 mi., 8.3 light-minutes) |

| spectral type | G2V |

| diameter | 1,392,000 km (865,000 mi.) |

| surface temperature | 5,400ºC (9,800ºF) |

| central temperature | 14 million ºC (25 million ºF) |

| mass (Earth = 1) | 332,946 |

| density (water = 1) | 1.409 |

| surface gravity (Earth =1) | 27.90 |

| escape velocity | 617.5 km/s (383.8 mi./s) |

| rotation period | 25.38 days |

| apparent magnitude | -26.8 |

| absolute magnitude | 4.83 |

Reference

1. Kuhn, J. R., Bush, R., Emilio, M., and Scholl, I. F. "The precise solar shape and its variability. Science, 2012; DOI: 10.1126/science.1223231.