expansion of Christianity

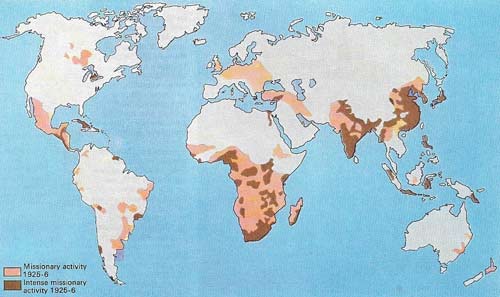

Figure 1. Christian missionary work greatly expanded from 1815 into the 20th century. As well as a revival of Roman Catholic missions there was an upsurge of Protestant activity, characterised by a notable degree of cooperation. This culminated in the international Missionary Council set up in 1921, which assisted and stimulated missionary activity throughout the world until it merged with the World Council of Churches in 1961. This map shows its activity in the mid-1920s. More than 1,000 million people were claimed to be Christians, in 1965 divided as follows: North America, 226 million; South America, 200 million; Europe, 515 million; Africa, 90 million; Oceania, 7 million.

Figure 2. This roadside shrine in Otovalo, Ecuador, symbolises the assimilation of religion at grass roots level. The Church, although concerned with Indian welfare, aided their cultural decline by supporting their employment in the mines.

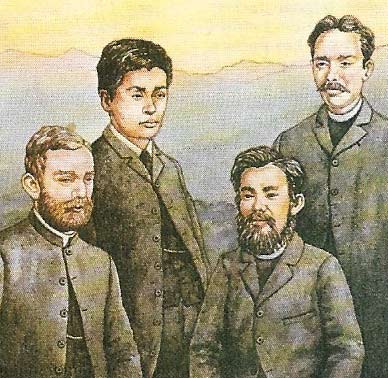

Figure 3. Christianity in Japan arrived with the Portuguese in the mid-16th century, but its presence became a source of suspicion within a few decades. In 1637, many thousands of Christian converts were massacred. The succeeding isolation of Japan was finally broken in 1858 and missionary work resumed, making notable contributions to education. Hugh Foss, one of the first missionaries, became Bishop of Osaka in 1899. He is seen here (left) with native clergy.

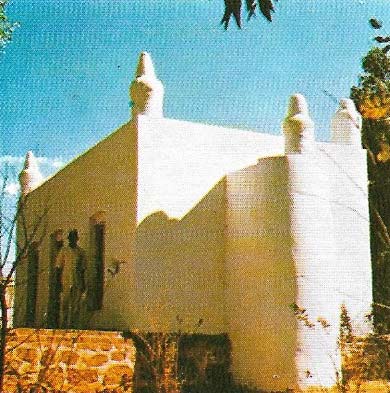

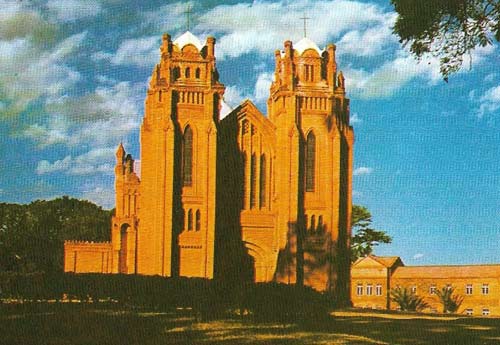

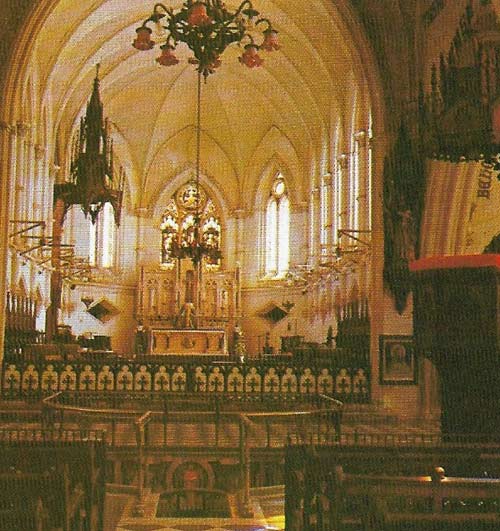

Figure 4. A mosque in Malawi (top) stands in stark contrast to its Christian counterpart (bottom) and marks one point where Islam and Christianity competed for the souls of inhabitants in central Africa. The church built by the Church of Scotland mission in Blantyre, Malawi, in the late 19th century, symbolizes the permanence of its missionaries' work in the old British central Africa.

Figure 5. Christian spires dominated the waterfront of Canton, in southern China. It was there that Jesuits arrived in 16th-century China after the successful pioneering work of Matteo Ricci. Canton became an important port of entry into China for later missionaries, who were able to establish colleges and hospitals there.

Figure 6. British domination in India were the focus of increasing missionary endeavour in the late 18th and 19th centuries, initially centered on the work of medical doctors. After the pioneering work of Alexander Duff (1806–1878) in Calcutta in the 1830s, Christianity became a central force in the education system established by the British. But it failed to make large inroads into the native religions, especially after the mutiny of 1857–1858 led to a new realization of the importance of indigenous culture. Here St Madras reflects the uncompromising application of Christianity in the Victorian mold.

The spread of Christianity across the world took place in stages. The first saw the new religion spread from its birthplace in Palestine into the wider Roman world during the first few centuries of its existence. The second was the early medieval period when the faith survived the tumult of the Dark Ages and most of Europe became Christian. The third stage began in the fifteenth century when European civilization and Christianity turned to the oceans and the lands beyond Islam in the Near East.

The instrument of conquest

The founding of the Portuguese and Spanish empires in the Americas in the fifteenth century, and along the coastline of Africa, the Indies, and the Pacific, gave an immense impetus to the advance of Roman Catholicism. The world was divided by a papal bull in 1493 into spheres of influence for the Catholic crowns of Portugal and Spain and the Church itself became an instrument of conquest and colonization.

|

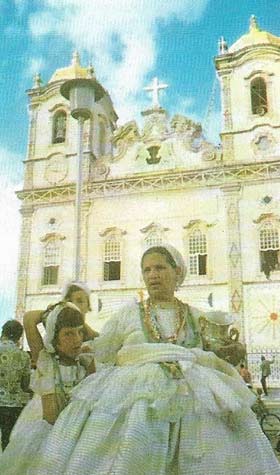

| The Church in Brazil, as in the Spanish colonies, was closely linked to the state despite Rome's influence over the Jesuits. Portuguese churches, such as this one in Salvador, tended to be less opulent than those built by the Spaniards. |

In some instances whole populations in the newly discovered lands were forcibly converted and there were other abuses of colonial power. Often the Catholic missions were outspoken critics of these abuses, none more so than the Protector General of the Spanish Caribbean, Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566). Catholic advances were not, however, confined to territories formally ruled by Spanish or Portuguese governors.

The foremost Jesuit missionary, Francis Xavier (1506–1552), was Papal Nuncio over the Portuguese Indian settlements. He went on to found a mission in Japan and died near Macao, in China. Another Jesuit, Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), was responsible for bringing Catholicism to China, where for a time it enjoyed the protection of the emperors and made many converts. Only in the eighteenth century did squabbles within the Church bring it into disrepute, so that Catholicism was repressed and by the end of the century the numbers of Catholics in China had become much reduced.

The success of the mission to Japan was less impressive. For 50 years from 1587 the Church was severely persecuted, and few Christians survived.

Protestant forms of Christianity were taken to those parts of the world where large numbers of Europeans settled – notably North America (except in French Canada, where the settlers were Catholics), and later South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand; but the 17th and early 18th centuries were a time of dormant missionary activity. The main exception to the lack of interest was the work of the Moravian and other German Pietist groups; these were to inspire later Protestant missionaries.

Christianity and colonial activity

The second great spurt of missionary activity took place at the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th, and was closely connected with the Protestant revival in northwestern Europe. The new Christian advance coincided with the increase of European colonial activity in the generally densely populated, tropical parts of the world, notably India and Africa, and with the ferment of the French and Industrial Revolutions. A spate of well-organized and often financially powerful societies were formed – the British Baptist Missionary Society in 1792, which sent missionaries to India; the Nonconformist London Missionary Society in 1795; The Netherlands Missionary Society in 1797; the Church of England Church Missionary Society in 1799; the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1810; and the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society in 1813 (various Scottish Presbyterian societies came together about the same time). The interdenominational Basel Missionary Society, with support from Germany and Switzerland, was founded in 1815. Some of the great names associated with these Protestant missionary societies in Britain were the Baptist William Carey (1761–1834), William Wilberforce (1759–1833), who was also leader in the successful campaign for the abolition of slavery, and David Livingstone (1813–1873).

|

| The Igbo of southeast Nigeria, like a number of ethnic groups in Africa, were receptive to Christianity and education under British colonial and missionary influence in the 19th century. The Christian faith was often merged with existing faiths, which included belief in a creator god as well as numerous other deities and spirits. The mask illustrated reflects this assimilation. Carved in wood it depicts Christ on the cross, flanked by angels. The Igbo mask is the basis of a long tradition still vigorously maintained. It is employed in various dramas such as the invocation of the gods, or initiation, as well as specifically Christian festivals. |

Catholic revival in the nineteenth century

By the end of the 19th century, more than 300 such societies or boards existed. Catholic missionary activity, at first slow to revive, produced an effect as large as that of the Protestants – perhaps, in terms of numbers of converts, even larger. One of the foremost Catholic missionary societies was the mainly French White Fathers.

The result of all these remarkable missionary efforts, which continued from the 19th century into the 20th, was the spread of Christianity over much of the tropical world. It did not make great advances in areas where other religions with claims to universality, particularly Islam, were strong. Indeed, at the same time as the spurt of Christian missionary activity at the end of the 1700s there was a revival of Islam, which made gains on the periphery of the older heartlands of the religion, especially in Indonesia and Africa (Figure 4).

Although most of the 19th-century missionary societies were rivals, the decline of European imperialism after World War I brought a wider, more international approach. These resulted in the formation of the World Council of Churches in 1948. This body did not include the Roman Catholic Church, but ties between Catholicism and the Council have grown increasingly close.