carts, coaches, and carriages

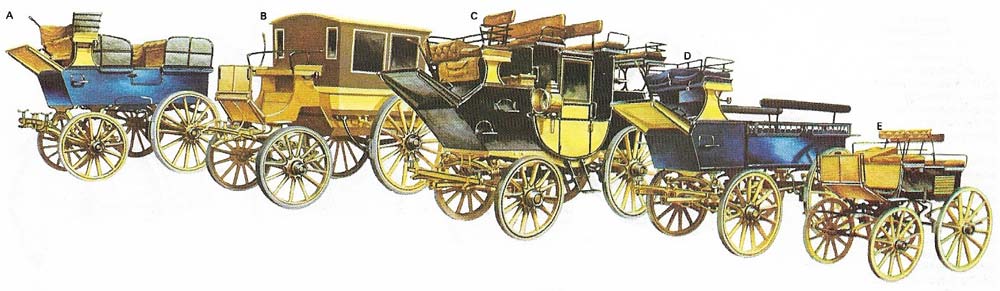

Figure 1. The charabanc (A) was useful in large establishments for communal transport. A private omnibus (B), driven by a liveried coachman, was used to carry small groups on excursions. The drag (C) was a private coach based on earlier mail coach designs. The wagonette (D), with seats down each side and a rear entrance, was fashionable for family outings. The dog cart (E), originally designed to carry sportsmen and their dogs, became widely used for everyday transport.

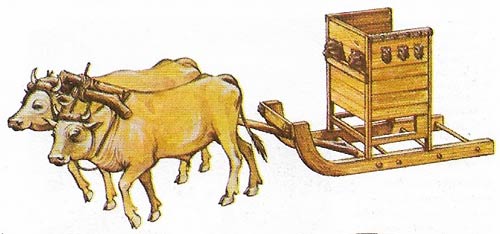

Figure 2. A sled was used by the Babylonians in about 2000 BC. The wheel was already in use in this region but an oxen-hauled sled, although slow, would have been useful for travel over the rough land.

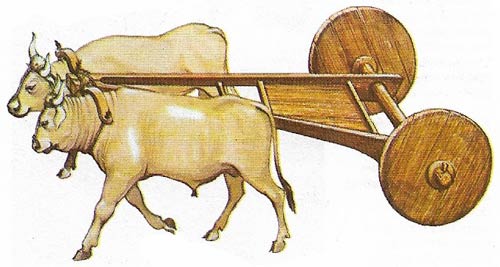

Figure 3. Wagons with four wheels were difficult to steer. This light A-framed ox-cart of about 2000 BC (from Armenia) avoided the problem by using only two wheels.

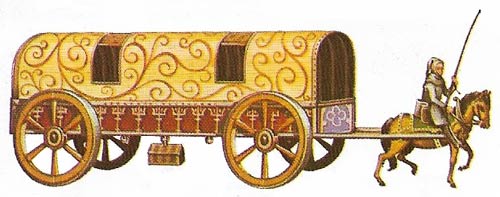

Figure 4. Horses, mules, and pack animals were the main forms of transport in the Middle Ages but this type of "long-wagon" was used to carry womenfolk of rank and wealth in relative comfort.

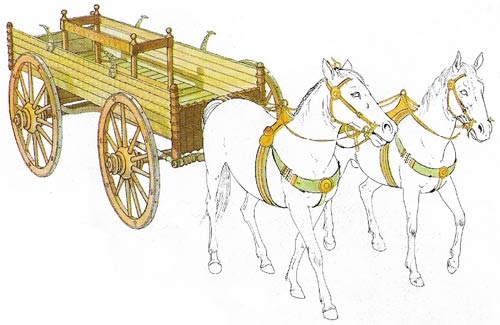

Figure 5. Early Mesopotamian civilizations had cattle, sheep, goats – but no horses. Horses were first found and then tamed on the plains of central Asia. Early Celts had very little knowledge of either wagons or horses but by the first century BC a considerable advancement had been made in the design and use of horsedrawn transport, as shown by this illustration of a two-horse ceremonial Celtic or Teutonic wagon used on feast days. The picture was reconstructed from fragments found on the western coast of Jutland, Denmark.

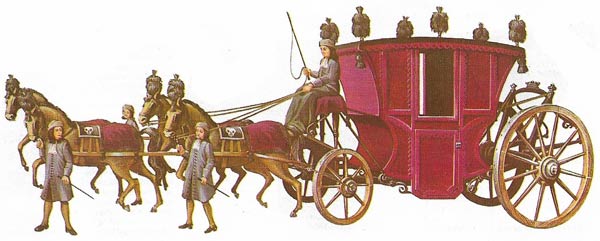

Figure 6. French elegance can be seen in the design of this heavy seventeenth-century funeral coach. Leather strap suspension and the large rear wheels(the front wheels were smaller to allow them to turn on a central steering pivot without fouling the body) gave passengers in this type of coach a reasonably comfortable rise on roads that had improved little for about a thousand years. In Britain, Charles II issued a royal charter to all coach-makers demanding their attention be paid to the problems of transport.

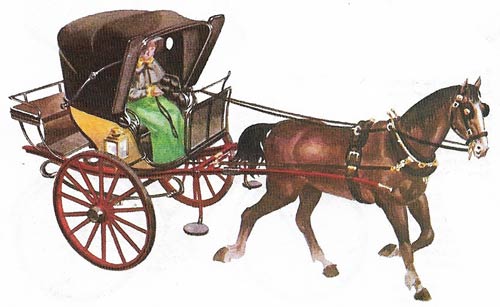

Figure 7. European carriage design influenced many early American models. But the buggy had a very definite North American character, although the word "buggy" was originally an English word meaning a hooded gig. The distinctive American buggy, which made its appearance in about 1850, was a light, fast carriage with two or four high wheels and a thin frame supporting the carriage and canopy. It was drawn by a single horse and seated two passengers.

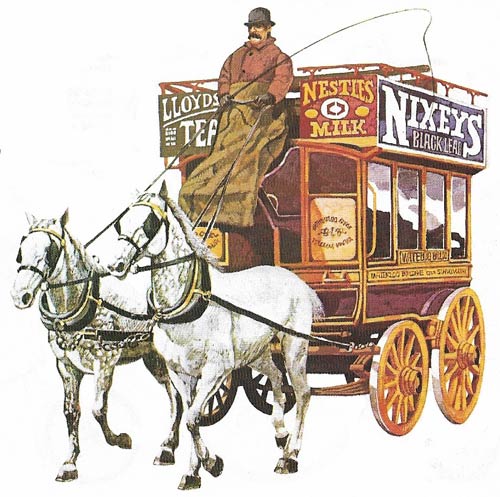

Figure 8. The word "omnibus" (meaning "for everyone") originated in France in about 1825 for a transport service operating in Nantes. Introduced to London in 1829 by Englishman George Shillibeer (1797–1866) the omnibus was an immediate success. The initial service, which ran between Paddington and the Bank for a fare of one shilling, was provided by a horse-drawn vehicle carrying 18 to 22 passengers. A liveried conductor stood guard by the rear entrance door. Soon people adopted the practice of perching on the roof of these single-deckers, leading to the development of the double-decker "knifeboard" bus with no weather protection on the upper deck(fares on top were half price). By the 1880s it had developed into the two-horse "garden seat" bus pictured here, in which forward-facing seats replaced the long bench. Horse-bus services operated in London until 1914.

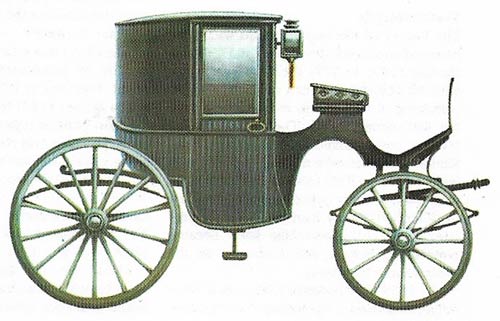

Figure 9. The brougham, a type of small, closed carriage for town and winter use, was first made in 1839 for Lord Brougham (1778–1868). It was unique in Britain and led to a revolution in carriage design, although similar vehicles were already in use in Paris. Eventually the brougham became on of the most common town carriages. The original version, known as the single brougham, was drawn by one horse and carried two people. Later models, known as bow-fronted and double broughams, were drawn by two horses and carried up to four people.

When early humans were hunters they found that they could transport a kill more easily if it were dragged it on a crude sled (Figure 2) rather than carrying it on one's back. Soon it was found that lengths of tree trunks used as rollers could move even heavier loads.

A solid wheel fixed to a platform by a simple axle was a logical development of the roller system (Figure 3). The first reported use of a wheel was in Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, some 5,000 years ago. Oxen-hauled wheeled transport then developed and its use spread slowly to the Mediterranean, Europe and China. When the Romans turned their attention to the building of wheeled vehicles their fine roads permitted fast travel in horse-drawn chariots – an important factor in the administration of a vast empire.

In the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the fifteenth century, progress in the development of vehicular transport lapsed. Most travellers were soldiers, pilgrims or pedlars who relied largely on horses or pack animals. Farm carts used for local haulage were drawn by heavy horses specially bred for the work and in later times used as battle chargers. The few wheeled vehicles of the Middle Ages had no springs (Figure 5) and a long journey through Europe could take several uncomfortable months.

Wheeled transport develops

As communication between peoples increased, carriage transport began to develop. The first vehicles used rigid axles until suspensions in the form of flexible wood laths, then leather straps, were introduced. Early 16th-century carriages, often extravagantly decorated, were much resented. The public envied those rich enough to afford them, the Church considered private conveyances sinful and the authorities kept a close watch, thinking them ripe for taxing – attitudes very similar to the ones of those who opposed the introduction of the automobile some 400 years later.

By the 17th century, the period of mechanical and scientific awakening in Western Europe, some coaches and carriages had metal spring suspensions. Large rear wheels allowed the vehicles to travel at higher speeds over the poor roads and also provided a more comfortable ride.

During the seventeenth century Britain changed, mainly because of trade, from a farming community to a commercial nation with the need to convey goods and people over long distances. Smaller, lighter vehicles were developed for rapid short trips. But for longer journeys the early stage-coaches could travel little more than 48 kilometers (30 miles) a day, stopping periodically at staging posts. A journey from London to Edinburgh – a distance of 675 kilometers (420 miles) – took 12 days even by fast coach.

From mail coach to rail travel

The first coaches to carry both mail and passengers travelled from Bath to London in 1783. Mail coaches were so reliable that clocks could be set by their 16 kilometers per hour (10 mph) schedule. Coaching inns, some of them able to cater for up to a hundred coaches a day, provided passengers with meals and accommodation along the main routes.

The 19th century saw great changes, including the brief introduction of steam coaches. Travelling became more comfortable with the development of elliptical leaf springs made of several thin, flat springs bound together and these are still used for many purposes today. The design of carriages and coaches became more elegant and light following the improvement of roads by the engineer John McAdam (1756–1836) whose type of road surfacing, designed to compact by the weight of passing traffic, greatly facilitated travel.

The Victorians used numerous types of horse-drawn transport for short journeys, ranging from the light gig to the family brake. Wealthy families kept staff to drive or maintain a private coach or drag, a dog cart for sportsmen and gun dogs, a governess cart for the children, a phaeton for rapid journeys, a victoria for park and town use, a brougham for privacy and perhaps a stately landau for formal occasions.

In America the stagecoach enjoyed a longer span of life and helped to open up the West through a vast network of scheduled services operated by coaching companies such as Wells Fargo. The lightweight high-wheeled buggy (Figure 7) and canopied phaeton or surrey were extensively used for private transport. Both were distinctively North American vehicles. A buggy seated two people whereas a surrey was essentially a family transporter with two rows of seats.

Cabs, trams, and buses

In Europe the hire-cab designed by Joseph Hansom (1803–1882) in 1834 (and bearing his name) plied the streets of almost every city and horse-drawn trams and omnibuses provided reasonably inexpensive travel for the masses. The box-like omnibus (Figure 8), French in origin, was first introduced to London in 1829 by George Shillibeer at the time of the demise of the coach. By the 1840s the single-decker bus had developed into the double-decker with seating along the length of the top deck. With further development improvements were added and the double-decker became the design adopted by bus companies when motor-driven transport began to replace horse-drawn vehicles. The last London horse bus in regular service continued to operate until 1914.