Latin American independence

Figure 1. On the eve of the wars of Independence (c. 1800) Latin America was divided between Spain and Portugal. The newly independent states agreed among themselves to keep their national boundaries generally in line with the old colonial administrative divisions. But because these were often not clearly demarcated, territorial disputes inevitably arose. The Banda Oriental (the east bank of the Rio de la Plata) had been a particular bone of contention between Spain and Portugal and contributed to be such between Argentina and Brazil after independence. Following a war between these countries (1825–1828) and diplomatic intervention by Britain, the disputed territory became a buffer state – the new republic of Uruguay.

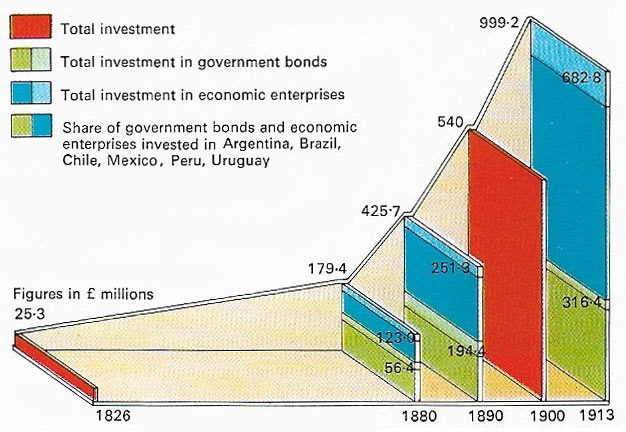

Figure 2. Britain's significant influence on the newly independent countries of Latin America was exerted primarily through commerce and finance. The massive inflow of British capital reached a peak from 1904–1913, when it accounted for at least 20% of all British investment abroad.

Figure 3. A church in Quito, capital of Ecuador, with an ornate and richly sculptured structure reflects the power and wealth of the Church in Latin America, both in colonial and modern times. But Church-state relations were generally uneasy following independence.

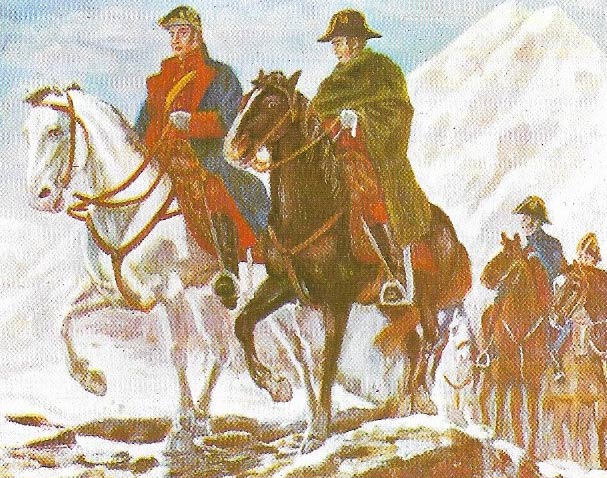

Figure 4. San Martin's "Army of the Andes" crossed the mountains through the Uspallata pass at a height of 3,799 meters (12,464 feet) – an extraordinary military achievement. The army was on its way to liberate Chile, in cooperation with the Chilean patriot Bernardo O'Higgins (1778–1842). The Spanish forces in Chile were taken completely by surprise and routed at Chacabuco on February 12, 1817. In the following April, a victory at Maipu ensured the independence of Chile.

Figure 5. Bolivar triumphantly accepts the surrender of the Spanish at the Battle of Boyaca (1819), assuring Colombia's independence.

Figure 6. Latin America in 1903 looked much as it does today. Mexico had long before lost more than half its national territory (the former Viceroyalty of New Spain) to the United States. Cuba and Panama had become nominally independent, although virtually protectorates of the United States, in 1902 and 1903 respectively. Paraguay had declared itself independent in 1842. Bolivia had lost its coastal territory to Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879–1883) and was now landlocked. Central America had dissolved into its constituent states (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua) as early as 1838.

Most of the 20 republics that comprise present-day Latin America became independent between 1810 and 1824 – the period that began after juntas set up in major cities of the Spanish American Empire had refused to accept Napoleon's brother Joseph as their ruler and ended with the last significant battle for freedom, at Ayacucho in Peru.

|

| Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844) was imposed on Spain by his elder brother Napoleon after the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula (1807–1808). This forced the issue of Latin American independence. When the French deposed Ferdinand VII (1784–1833) of Spain and then threatened Portugal, the Spanish Americans at first pledged loyalty to Ferdinand but later declared for independence. The Portuguese royal family fled briefly to Brazil and the king's son stayed as regent of Brazil, declaring it independent in 1822. |

Haiti had seized independence from France some years earlier, in 1804. The Haitians subsequently imposed their rule upon neighboring Santo Domingo, which did not achieve freedom as the Dominican Republic until 1844. Brazil, the Portuguese Empire America, became independent with very little bloodshed in 1822 and the Prince regent, Dom Pedro I, was crowned its emperor. Uruguay emerged as a separate state in 1828 after Argentina and Brazil had fought to claim it. Cuba remained a Spanish possession until the end of the nineteenth century, when the Spanish-American War (1898) led to its becoming independent although bound by close ties with the United States. Panama was a province of Colombia until 1903, when its inhabitants successfully revolted. Its new government leased in perpetuity to the United States (which had assisted the revolt) the strip of land 16 kilometers (10 miles) wide through which the Panama Canal, completed in 1914, was to be cut.

The consequences of independence

The independence of Latin America meant essentially that men of European stock who were born there replaced men from the Iberian Peninsula in positions of power and privilege. The social structure inherited from Spain and Portugal remained virtually intact typified by hacienda or great landed estate. The Church, allied with the Crown in the colonial period, continued to exercise a strong conservative influence (Figure 3) and the military, greatly strengthened by the prolonged wars, was another privileged institution and one that prejudiced the establishment of effective civilian government.

|

| Native indians generally viewed Latin American independence as no more than a change of masters. Many who had been subject to the old forms of colonial bondage became peones (peasant laborers) on the great estates. |

The vast size of many of the new states, problems of communication, economic dislocation brought about by the wars, lack of experience in administration on the part of the new rulers and the illiteracy of the masses all contributed to make stable government extremely difficult. Few of the hero's of independence were able to govern successfully when peace came to their countries. Simon Bolivar (1783–1830), the greatest of them, died in self-imposed exile; Jose de San Martin (1778–1850), the other outstanding liberator of Spanish America, decided to retire to Europe. The characteristic ruler of the new countries was the caudillo, or military dictator.

|

| Simón Bolivar, known throughout the continent as "The Liberator", was the greatest hero of Latin American independence. He played a leading part in winning freedom for his native land Venezuela, as well as Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, the country named after him. Bolivar brought together the first three of these countries in one state, the republic of Colombia, and he inspired the Congress of Panama (1826) with the principal aim of establishing a league of Spanish-American nations. But the league did not materialise: Greater Colombia split into its constituent states, and Bolivar died, deeply disillusioned, in 1830. |

|

| Jose de San Martin was the outstanding liberator of southern South America. He assured independence for Argentina and gained it for Chile and part of Peru (including Lima, the capital). While the liberation of Peru, the last great stronghold of Spanish power, was incomplete, San Martin had a famous meeting with Bolivar at Guayaquil in Ecuador (July 1822) to discuss the future of Spanish America. San Martin then withdrew, leaving the field to Bolivar. |

Relationships between countries

Relations between the Latin American countries following independence were generally neither close nor friendly. While Portuguese America remained intact (as Brazil), Spanish America had disintegrated along the lines of the old imperial administrative divisions. These divisions were accepted basis for the new states, but there were often disputes over ill-defined boundaries. Geography And history have combined to isolate the countries of Latin America from each other. Formidable physical barriers have been a major cause of this isolation, as well as regionalism within individual countries. Curing the colonial era the viceroyalties, captaincies-general, and presidencies into which the Spanish American Empire was divided were linked to the mother country rather than to each other. Since independence, relations with powers outside the region generally have been much more important than those among the Latin American countries themselves. Colonial trading patterns continued after independence. Most countries had to rely on exporting one or two primary products and on importing manufactured goods.

Dependence on other countries

The new states of Latin America this became economically and financially dependent upon powerful external countries. During the nineteenth century Great Britain was the major economic power in Latin America (Figure 2). British capital played a key role in the economic development of Argentina in the latter part of the century. Her naval power forced Brazil to acquiesce in efforts to stamp out the slave trade. The eventual abolition of slavery itself was one of the main causes of the overthrow of the Brazilian emperor and the establishment of a republic in 1889.

By that time the United States had greatly increased its territory at the expense of Mexico, which it defeated in war (1846–1848). Even earlier, in 1823, President Monroe (1758–1831) had enunciated his famous "Doctrine". This warned European powers against incursions or further colonization in Latin America and implied that the United States had a special relationship with Latin America. By the end of the nineteenth century the United States, with military strength, was able to compel respect for the Monroe Doctrine when its own interests were at stake. At the same time it promoted "pan-Americanism", embodying the idea that the countries of the Americas shared a community of interests and a special "system" of international relations: the inter-American system. A conference of the United States and Latin American countries in Washington (1889–1890) set up the International Union of American Republic – renamed the Pan American Union in 1910.