Russia under Stalin

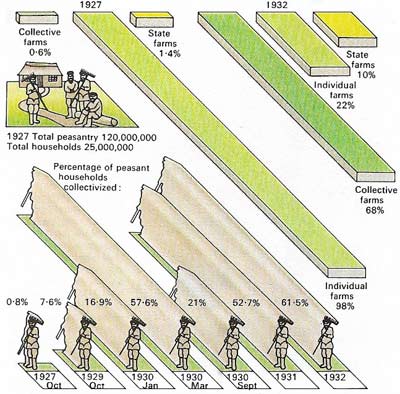

Figure 1. The New Economic Policy was a compromise on the way to socialism. It permitted the blossoming a private farming and since four out of five Soviet citizens lived in the countryside there was a risk of the capitalist ethic proving attractive. Lenin had preached cooperation and Bukharin ably elucidated his views after 1924. When agricultural production climbed back after 1924 to the level of 1913, the Soviets were faced with a choice – allow private agriculture to develop and provide the basis for overall economic growth, or socialize agriculture and base economic growth on industrial development. They chose the latter out of fear that private agriculture could overturn the socialist state and Stalin wanted food supplies for the urban worker.

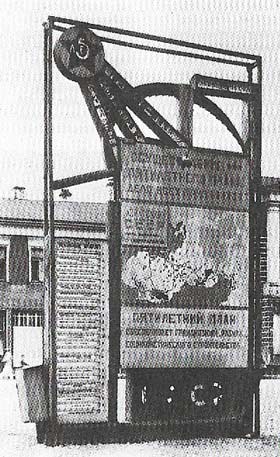

Figure 2. The tractor was the symbol of Soviet power in the Russian countryside. The collective farm or kolkhoz became the dominant enterprise in socialist agriculture after 1928. Much virgin land was brought into cultivation in the 1930s and sovhozes or state farms were usually set up in new areas. Collective farm peasants were permitted a small, private plot and some animals. They received a share of the produce in proportion to the net income of the kolkhoz.

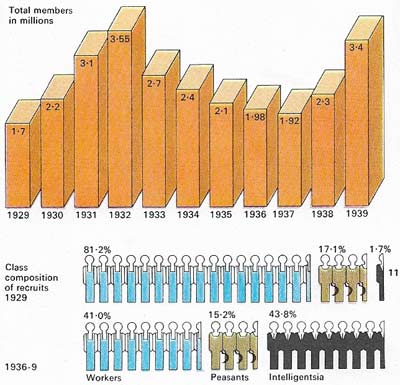

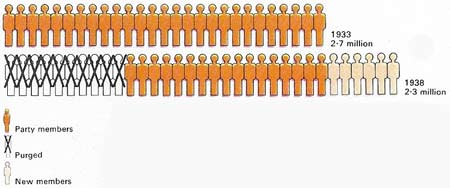

Figure 3. The "purges of the 1930s" were in fact composed of many different operations; these gathered momentum and reached a crescendo in the "Yezhovschina" (named after Yezhov, the head of Internal Affairs) of 1937–1938. The first purge was launched by the party in January 1933. In 1935 a "verification of party documents" was ordered. About one member in five was expelled, including recent workers and peasant recruits. About 9% had been purged before the "show trials" ushered in the devastating Great Purge of 1936–1938, when millions perished in the party and populace alike.

Figure 4. The "purges of the 1930s" were in fact composed of many different operations; these gathered momentum and reached a crescendo in the "Yezhovschina" (named after Yezhov, the head of Internal Affairs) of 1937-1938. The first purge was launched by the party in January 1933. In 1935 a "verification of party documents" was ordered. About one member in five was expelled, including recent workers and peasant recruits. About 9% had been purged before the "show trials" ushered in the devastating Great Purge of 1936–1938, when millions perished in the party and populace alike.

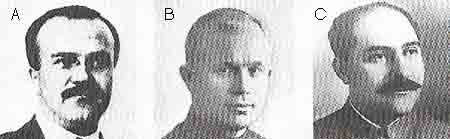

Figure 5. (A) Vyacheslav Molotov (1890-1986) became a full member of the Politburo in 1926. He was instrumental in shaping the nonaggression pact with the Nazis and he remained a loyal servant to Stalin. He was also involved in party construction. (B) Nikita Khrushchev (1894 to 1971) was on the Moscow party committee between 1932 and 1938, when he took the key post of First Secretary of the party in the Ukraine. He became a member of the Politburo in 1939 where he backed Stalin. (C) Lazar Kaganovich (1893–1991) became a full member of the Politburo in 1930. He headed the Moscow party Committee 1930–1935 and was minister of transport 1935–1944. A loyal supporter of Stalin, he retained favor during the years 1930–1953.

Figure 6. Stalin misjudged fascism in the early 1930s but when he realized the danger he launched the "Popular Front" policy in 1935. All progressive forces were to unite against the common enemy and posters declared: "Let's mercilessly rout and destroy the enemy". This policy did not deter Germany, and Stalin, thinking he understood Hitler, signed the pact of August 1939. Stalin intended to intervene opportunely in the impending war when Hitler had become over-committed on the Western Front. Stalin was so thunderstruck by the invasion of June 1941 that he lost his nerve and failed to provide resolute leadership during the first days of the war. The failure of the German Blitzkrieg in 1941–1942 to overrun the USSR meant that the war of attrition, which Germany could not win because of inadequate resources, became inevitable. Major battles were Moscow and Stalingrad.

Figure 7. "Lenin is the Marx of our time" was the slogan when Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (left) was alive. Soon a new form appeared: "Stalin is our Lenin". Stalin became the main interpreter of Marx's chief Russian disciple. Those who threatened his supremacy were soon removed from positions of power.

The Soviet Union's evolution between 1917 and 1953 was dominated by two men, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870–1924) and Joseph Stalin (1879–1953) (Key). While Lenin was alive he was the main driving force behind events. Nevertheless there were other important personalities, such as Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), Nikolai Bukharin (1888–1938), Mikhail Tomsky (1880–1936), Grigori Zinoviev (1883–1936), and Anatoli Lunacharsky (1875–1933), to name only a few. All made an original contribution to Soviet development. Lenin, a man of outstanding intellectual ability, would listen to an opposing point of view if it came from one of his supporters, but had noticeably less respect for the views of his outspoken political opponents.

|

| An outstanding theorist, Trotsky was, however, a poor politician, ill at ease with the minutiae of government. Although expected to succeed Lenin, he was inept at intrigue and was defeated. It was his failure to perceive the machinations of his fellows that soon led to his exile and death. He was an unequaled speaker but his independent, critical attitude was not tolerated by Stalin. |

|

| Lenin called Bukharin "the darling of the whole part" and its "most valuable and most powerful theorist". Bukharin was the leading party writer on economic subjects. He sided with Stalin against Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev and was a leading defender of the New Economic Policy. He was swept aside at the end of the 1920s when collectivization became the new official policy. |

The policies of Stalin

Lenin realized the importance of consolidating the revolution, Stalin developed and extended the means. He sanctioned the revolutionary violence of the Cheka and extended the primacy of the party in state affairs. His doctrine of "Socialism in One Country" meant that all foreign communist parties became subservient to Soviet interests through the Comintern (Communist International). Furthermore, he continued to hold the show trials of a number of so-called counter revolutionaries. The first took place in 1922 and were directed at the Socialist Revolutionaries.

Nevertheless, there were major differences between the two men. Stalin was an intuitive anti-intellectual. His intellectual insecurity did not permit him to envisage a policy and then take on his opponents in open debate. Instead he sought to outmaneuver them in labyrinthine intrigue. Lenin was good at placing labels, often misleading ones, on his opponents; Stalin was a past master at the art. Lenin used the Cheka and the show trial against non-Bolsheviks; Stalin used them against the Communist Party as well.

The achievement of power

Stalin built up his power by his administrative skills and filled the leading party bodies with workers, but he did take the precaution of first briefing them on how to vote.

Stalin's journey on the way to supreme power can be divided into three stages, the completion of each marking a significant step forward. The first, terminating in 1928–1929, saw him with almost total control over the apparatus of the Russian Communist Party which, because of the events of the immediate post-October period, had inherited the dominant role in the state. Victory over the party was not sufficient to permit Stalin to reach out to every corner of the Soviet Union. This he did during the 1930s when collectivization and industrialization transformed the scene (Figure 1). The peasants lost their land and their livestock and were brought under complete state control. The foundations of great industrial advance were laid with heavy industry, vital for defense, receiving top priority. A terrible massacre of real, putative, imaginary, and potential opponents of Stalin's dictatorship took place. No one was secure, whether top party official (a major target were the Old Bolsheviks, those who had seized power with Lenin in October 1917), military leader, writer, peasant, worker, engineer, or foreign communist leader living in exile in the USSR. More than ten million people perished, including the great majority of the class of kulaks (well-to-do peasants).

|

| Soviet power was insecure without a strong industrial and military base. Ambition ran riot as the first Five Year Plan got underway in 1928. Production goals were pushed up in the belief that a revolutionary spirit could perform miracles. Heavy industry was favored at the expense of light industry and agriculture. Wonders were performed, but at appalling cost. Enthusiasm waned after the first plan and labor discipline became severe with saboteurs and counterrevolutionaries unmasked everywhere. Living standards dropped as millions flooded to the cities where accommodation was primitive. Both food and clothing were also in short supply. |

When this period ended Stalin was master of all he surveyed in Soviet Russia; he controlled the party, the government and the police. Through the agency of foreign communist parties he could influence the internal politics of other countries. The third phase, which began with the outbreak of World War II and ended with Stalin's death in March 1953, saw Stalinist Russia reach the peak of world influence.

Stalin exhibited great tactical skill in the 1920s in overcoming his competitors one by one. In 1923–1924 he allied himself with L. V. Kamenev (1883–1936) and Zinoviev against Trotsky; in 1925 he sided with Bukharin against Kamenev and Zinoviev; in 1926–1927 still with Bukharin (who realized too late that Stalin's allegiance was merely tactical) against Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev and finally in 1928–1929 he was strong enough to oppose Bukharin, Tomsky, and Rykov (1881–1938) by himself. By 1929 Trotsky was in exile and the others living on borrowed time. Most were to perish in the purges of 1936–1938 (Figures 3 and 4). Trotsky, exiled in Mexico, was murdered by Stalin's executioner in 1940.

Russia's development

Russia's industrial effort in the 1930s made great progress. The bases of a thriving heavy industry were established and were to prove of vital importance when war came. Stalin took a long time to learn foreign affairs (Figure 7). He indirectly helped Hitler gain power in Germany; then saw the danger and launched the Popular Front, inviting the collaboration of all democratic forces. He again put his faith in National Socialist Germany in 1939 and almost paid with the annihilation of the USSR after the Geririan attack of June 1941.

Stalin's war record, except for the opening days of the war when he lost his nerve, is admirable. He led by example and his ruthlessness steadied his armies. Stalin played a vital role in the victory of the Allies. But had he allied Soviet Russia with Britain and France in 1939, it is possible that Germany would not have attacked Poland.