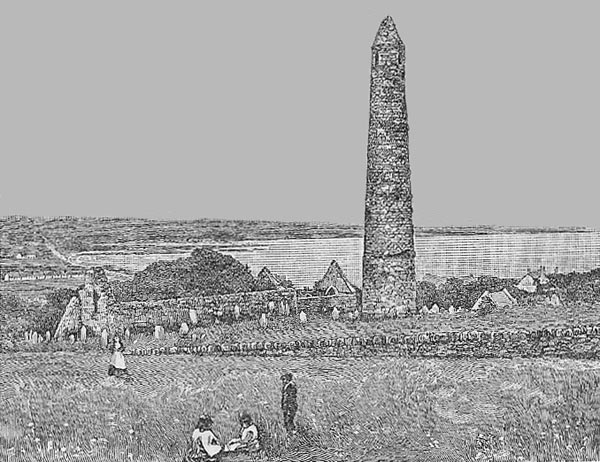

round tower

The round tower at Ardmore

A round towers is a tall narrow circular tower tapering gradually from the base to the summit, found abundantly in Ireland, and occasionally in Scotland. Round towers are among the earliest and most remarkable relics of the ecclesiastical architecture of the British Islands. They have long been the subject of conjecture and speculation, but there can be now no doubt that they are the work of Christian architects, and built for religious purposes.

Round towers seem to have been in all cases attached to the immediate neighborhood of a church or monastery, and, like other early church-towers, they were capable of being used as strongholds, into which, in times of danger, the ecclesiastics could retreat with their valuables.

In the Irish records, for two centuries after 950 AD, they are invariably called Cloictheack or bell-towers, and are often mentioned as special objects of attack by the Northmen. About 118 towers of this description are yet to be seen in Ireland, twenty of which are entire or nearly so; and Scotland possesses three similar. towers – at Brechin, Abernethy, and Eglishay in Orkney. They are usually capped by a conical roof, and divided into stories, sometimes by yet existing floors of masonry, though oftener the floors have been of wood. Ladders were the means of communication from story to story. There is generally a small window on each story, and four windows immediately below the conical roof. The door is in nearly all cases a considerable height from the ground.

The illustration here shows the tower at Ardmore, County Waterford, which is one of the most remarkable of those remaining in Ireland. Rising from a double plinth course at the bottom to a total height of 95 feet, it is divided into three stages by external bands at the offsets, corresponding to the levels of three floors within, the fourth being also marked by a slight offset. Most of these towers, however, have only a slight batter externally from top to bottom. Some, like that of Devenish, are carefully and strongly built of stones cut to the round, and laid in courses, with little cement; others, such as those at Cashel and Monasterboice, have the stones merely hammer-dressed and irregularly coursed; others, again, like those of Lusk and Clondalkin, are constructed of gathered stones untouched by hammer or chisel, roughly coursed, and jointed with coarse gravelly mortar; while in others, as at Kells and Drumlane, part of the tower is of ashlar, and the rest of rubble masonry.

The average height of these towers is from 100 to 120 feet, the average circumference at the base about 50 feet, and the average thickness of the wall at the base from 3 feet 6 inches to 4 feet; the average internal diameter at the level of the doorway is from 7 to 9 feet, and the average height of the doorway above the ground-level about 13 feet. These doorways always face the entrance of the church to which the towers belonged. All the apertures of the towers have inclined instead of perpendicular jambs, which is also an architectural characteristic of the churches of the same period, and the sculptured ornamentation of the apertures or walls of the towers is in the same style as that of the churches.

They are now assigned to a period ranging from the 9th to the 12th centuries. The source whence this form of tower was derived, and the cause why it was so long persisted in by the Irish architects, are points, however, on which there is not the same unanimity of opinion. Two round towers, similar to the Irish type, are to be seen in the yet extant plan of the monastery of St Gall in Switzerland, of the first half of the 9th century; and, in the Latin description attached to the plan, they are said to be ad universa superspicienda. The church and towers as rebuilt at that date are no longer in existence; but Miss Stokes has pointed out a passage in the life of St Tenenan of Brittany which shows that this type of round tower detached from the church was in use on the Continent in the 7th century, wherein to deposit the silver-plate and treasure of the church and protect them from the sacrilegious hands of the barbarians should they wish to pillage the church.' Lord. Dunraven has traced the type from Ireland through France to Ravenna, where there are still six remaining out of eleven recorded examples. Hulsch considers the detached round towers or campaniles of the Ravenna churches to be of the same date as the churches themselves, or mostly earlier than the close of the 6th century ; but Freeman, on the other hand, maintains that they are all later than the days of Charlemagne, as the local writer Agnellus, writing soon after his time, describes the churches of Ravenna much as they are, but says nothing of bell-towers. Suffolk and Norfolk contain more round-towered churches than does all the rest of England, probably because the flint there prevalent is worked into this form more readily than any other stone. A modern round tower is O'Connell's monument in Glasnevin Cemetery, which is 160 feet in height.