hyperbola

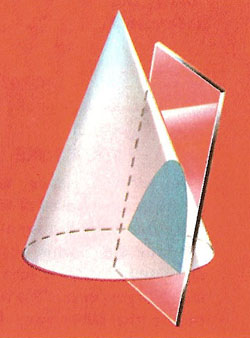

Figure 1. A hyperbola is formed when a plane cuts a cone at a slope greater than that of the sides of the cone.

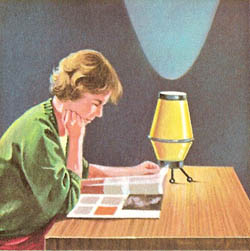

Figure 2. The cone of light emitted by a vertical lamp placed close to a wall is cut by the wall in a hyperbola.

Figure 3. If an object is traveling fast enough under the gravitational pull of the Earth, or any other astronomical body, then its path is hyperbolic. Hyperbolic curves can look much like parabolic curves, though they have different mathematical properties.

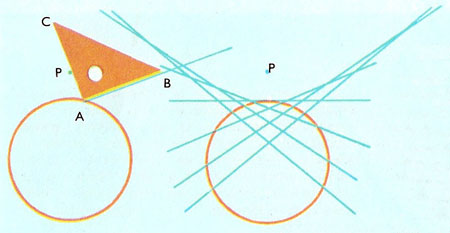

Figure 4. Construction of a hyperbola.

The hyperbola is one of the conic section family of curves, which also includes the circle, the ellipse, and the parabola. It is obtained if a double cone is cut by a plane inclined to the axis of the cone such that it meets both branches of the cone (Figure 1).

Of the four conic curves, the hyperbola is the one least encountered in everyday life. A rare chance to see the complete shape is when a lamp with a cylindrical or conical shade throws shadows on a nearby wall (Figure 2). Part of a hyperbola is produced by the liquid that climbs by capillary action between two microscope slides held vertically and almost touching.

A hyperbola is the path followed by a smaller object that is traveling fast enough to escape completely from the gravitational pull of a larger object (Figure 3). Some comets, for example, have hyperbolic orbits (also called "open" orbits) so that, after one swing around the Sun, they head off into interstellar space never to return. It can be difficult to tell, in some cases, whether a comet's orbit is hyperbolic or is highly elliptical and, therefore, closed. In fact, one way to think of a hyperbola is as a kind of ellipse that is split in half by infinity.

Hyperbola and ellipse

Not surprisingly, the hyperbola and the ellipse share many inverse relationships. For example, whereas the ellipse is the locus of all points whose distances from two fixed points, called foci, have a constant sum, the hyperbola is the locus of all points whose distances, r1 and r2, from two fixed points, F1 and F2, is a constant difference, r2 – r1 = k. If a is the distance from the origin to either of the x-intercepts of the hyperbola, then k = 2a. Also, let the distance between the foci, F2 – F1 = 2c. Then the eccentricity, a measure of the flatness of the hyperbola, is given by e = c/a. For all hyperbolas, e > 1; the larger the value of e, the more the hyperbola resembles two parallel lines. Just as the circle (for which e = 0) is the limiting case of the ellipse (for which 0 < e < 1), so the parabola (e = 1) is the limiting case of both the ellipse and the hyperbola.

Asymptotes and axes

A hyperbola has two asymptotes: the never-quite-attainable limits of the curve's branches as they run away to infinity. The transverse axis of the hyperbola is the line on which both foci lie and that also intersects both vertices (turning points); the conjugate axis goes through the center and is perpendicular to the transverse axis.

Rectangular hyperbola

|

A rectangular hyperbola has an eccentricity of √2 (see square root of 2), asymptotes that are mutually perpendicular, and the property that when stretched along one or both of its asymptotes, it remains unchanged. The standard equation of the rectangular hyperbola is xy = c, or y = c /x.

History of the hyperbola

The rectangular hyperbola was first studied by Menaechmus. Euclid and Aristaeus wrote about the general hyperbola but only studied one branch of it, while Apollonius was the first to study the two branches of the the hyperbola and is generally thought to have given it its present name.

How to construct a hyperbola

Draw a circle of radius about 1 inch (2½ centimeters). Mark a point half an inch outside the circumference. Place a set square so that the right-angled corner A is on the circle, and one side AC passes through P. Draw the line AB.

Repeat with different positions of the set square. The drawn lines will all touch a hyperbola (Figure 4).

Related curves

The pedal curve of a hyperbola with one focus as the pedal point is a circle. The pedal of a rectangular hyperbola with its center as pedal point is a lemniscate. The evolute of a hyperbola is a Lamé curve. If the center of a rectangular hyperbola is taken as the center of inversion, the rectangular hyperbola inverts to a lemniscate, while if the vertex is used as the center of inversion, the rectangular hyperbola inverts to a right strophoid. If the focus of a hyperbola is taken as the center of inversion, the hyperbola inverts to a limaçon. In this last case if the asymptotes of the hyperbola make an angle of π/3 with the axis which cuts the hyperbola then it inverts to the trisectrix of Maclaurin.

Hyperbolic velocity

Hyperbolic velocity is a velocity that exceeds the escape velocity of a celestial body, such as a star. It allows an object, such as a spacecraft or rogue planet, to break free of the gravitational attraction of the larger body by following an open, hyperbolic orbit (Figure 3).