Kepler, Johannes (1571–1630)

Figure 1. Johannes Kepler.

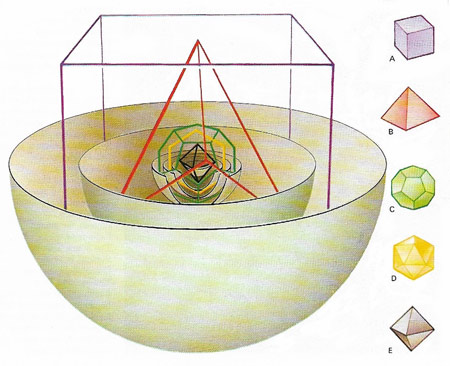

Figure 2. Kepler's theory of five regular solids shows that his ideas of provided a link between the past and the present. He believed that the five regular solids – the cube (A), tetrahedron (B), dodecahedron (C), icosahedron (D), and octahedron (E) – could be fitted inside the orbits of the various planets. He reasoned that thee were only five such solids and exactly five spaces between the six planets known at the time: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. It was his brilliant work, based upon observations made by Brahe, that showed the the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the Solar System..

Johannes Kepler was a German astronomer and mathematician, considered one of the founders of modern astronomy. Using positional data carefully amassed by Tycho Brahe, Kepler formulated his famous three laws (see Kepler's laws of planetary motion), including the crucial realization that planetary orbits are ellipses not circles.

Kepler and the heliocentric theory

Born in Weil der Stadt, southwest Germany, Kepler studied at the university of Tübingen and, as a graduate, was tutored by Michael Maestlin who introduced him to the heliocentric concepts of Copernicus. In 1597 he published Mysterium cosmographicum (The cosmographic mystery) in which (revealing his medieval mystical bent) he argued that the distances of the planets from the Sun in the Copernican system were determined by the five regular solids, if one supposed that a planet's orbit was circumscribed about one solid and inscribed in another.

Specifically, his theory states that if a sphere is drawn to touch the inside of the path of Saturn, and a cube is inscribed in the sphere, then the sphere inscribed in that cube is the sphere circumscribing the path of Jupiter. Then if a regular tetrahedron is drawn in the sphere inscribing the path of Jupiter, the insphere of the tetrahedron is the sphere circumscribing the path of Mars, and so inward, putting the regular dodecahedron between Mars and Earth, the regular icosahedron between Earth and Venus, and the regular octahedron between Venus and Mercury. Thus the number of (then known) planets is explained in terms of the five convex regular solids – the Platonic solids (see Fig 2). Although this idea seems to smack of Pythagorean mysticism, it ultimately stemmed from Kepler's belief that mathematical harmony was a reflection of God's perfection and, curiously, except for Mercury, Kepler's construction gave surprisingly accurate results.

Because of the mathematical skills Kepler showed in his Mysterium cosmographicum, he was invited by Tycho Brahe to Prague to become his assistant and to calculate new orbits for the planets from Tycho's observations. When Tycho died, in 1601, Kepler was appointed his successor as Imperial Mathematician, the most prestigious job in mathematics in Europe. In Prague, Kepler published Astronomia pars optica (The optical part of astronomy, 1604), in which he dealt with refraction and gave the first modern explanation of the workings of the eye; De stella nova (Concerning the new star, 1606) on the "new" star that had appeared in 1604 (see Kepler's Star); and Astronomia nova (New astronomy, 1609), which contained his first two laws (planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus, and a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times).

In 1610 Kepler heard about Galileo's discoveries with the telescope and wrote a long letter of support, which he published as Dissertatio cum nuncio sidereo (Conversation with the sidereal messenger). Later that year, he presented his own observations of Jupiter's moons. These writings gave tremendous support to Galileo, whose discoveries were being widely doubted and denounced by church authorities. Kepler went on to provide the beginning of a theory of the telescope in his Dioptrice (1611). A couple of years later he wrote De vero anno quo aeternus dei filius humanam naturam in utero benedictae Virginis Mariae assumpsit (Concerning the true year in which the son of God assumed a human nature in the uterus of the blessed virgin Mary), arguing that the Christian calendar was out by five years, and that Jesus had been born in 4 BC (a conclusion now widely accepted). Between 1617 and 1621 he published Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae (Epitome of Copernican astronomy), which became the most influential introduction to heliocentric astronomy.

In his Harmonice mundi (Harmony of the world, 1619), Kepler derived the heliocentric distances of the planets and their periods from considerations of musical harmony, and presented his third law, relating the periods of the planets to their mean orbital radii. His Tabulae Rudolphinae (Rudolphine tables, 1627), based on Tycho's observations and calculated according to the elliptical astronomy, were used into the eighteenth century.

Kepler's equation

Kepler's equation, first derived by Kepler in 1609 in his Astronomia nova, is one of the important formulae that enables the position of a body in an elliptical orbit to calculated at any given time from its orbital elements. It relates the mean anomaly, M, of the body to its eccentric anomaly, E, by the following:

M = E – e sin E

where e is the eccentricity of the orbit.

Kepler's other mathematical work

Kepler also did important work in optics, discovered two new regular polyhedra (1619), gave the first mathematical treatment of close packing of equal spheres (see Kepler's conjecture), which led to an explanation of the shape of the cells of a honeycomb (1611), gave the first proof of how logarithms worked (1624), and devised a method of finding the volumes enclosed by surfaces of revolution, which (with hindsight) can be seen as contributing to the development of calculus (1615–1616).

Book five of Harmonices mundi, in which Kepler offers a more elaborate version of his polyhedral model of the Solar System, he gives the first systematic treatment of tilings or tessellations, a proof that there are only thirteen Archimedean solids (convex uniform polyhedra), and the first account of two non-convex regular polyhedra, or what are now called see Kepler-Poinsot solids.

Kepler's mathematical work was full time and continued even during the wedding to his second wife in 1613. The dedicatory letter to a book he wrote shortly after explains that at the wedding celebrations he noticed that the volumes of wine barrels were estimated by means of a rod slipped in diagonally through the bung-hole, which prompted him to wonder how that could work. The result was a study of the volumes of solids of revolution called Nova stereometria doliorum (New stereometry of wine barrels, 1615).

Kepler and pluralism

Kepler exemplifies the resistance shown by some of the leading Renaissance scientists (including also Copernicus and Galileo) to the idea that there might be innumerable inhabited worlds. Having accepted that the Earth and other known planets revolve around the Sun, he was enthusiastic about the possibility of life in other parts of the solar system. However, he was resistant to the notion that the stars might have planetary systems of their own and questioned pluralism on theological grounds:

"If there are globes similar to our Earth ... Then how can we be masters of God's handiwork?" His relief upon hearing the details of Galileo's discovery of four satellites of Jupiter are evident in his published response: "If you had discovered any planets revolving around one of the fixed stars, there would now be waiting for me chains and a prison among Bruno's innumerabilities. I should say, exile to his infinite space."

In Kepler's opinion the newly-found moons were made by God for the benefit of the Jovian inhabitants: "Our Moon exists for us on Earth, not for the other globes. Those four little moons exist for Jupiter, not for us. Each planet in turn, together with its occupants, is served by its own satellites. From this line of reasoning we deduce with the highest degree of probability that Jupiter is inhabited."

His Somnium (The Dream), published posthumously in 1634, was a typical blend of reasoned 17th-century astronomy and lingering medieval supernaturalism. The hero of the piece, a young Icelander called Duracotus, travels to the Moon with the aid of his mother, who is an accomplished witch – an arrangement not unfamiliar to Kepler since his own mother was tried, though not convicted, of witchcraft.