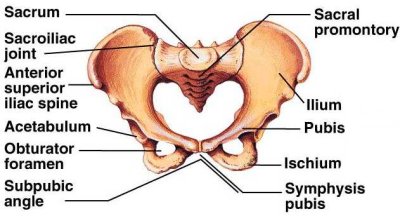

pelvis

Labeled diagram of the pelvis.

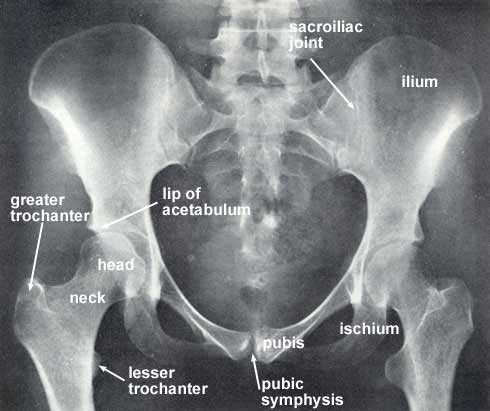

Radiograph of the pelvis and neighboring skeletal structures.

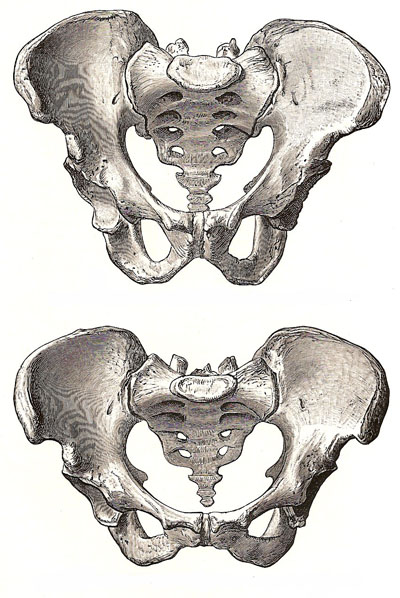

Male pelvis (top) and female pelvis (bottom) seen from the front.

The pelvis is a basin-shaped bony structure that supports the internal organs of the lower abdomen in humans and other vertebrates,

and serves as a point of attachment for muscles that move the lower limbs.

The pelvis consists of the sacrum (the triangular

spinal bone below the lumbar vertebrae), coccyx, and two innominate or hip-bones.

Each of the hip-bones, known also as the coxal or innominate bones, consists

of three parts – ilium, ischium,

and pubis – which are fused together.

When you put your hands on your hips, they are resting on your illia. The

hip-bones curve forwards to join at the symphysis pubis at the front.

The legs are connected to the pelvis by the hip joint. The head of the femur (thigh bone) fits inside a deep socket in the pelvis called the acetabulum to make the hip joint, which is a ball-and-socket joint.

In women, the pelvis is broader and shallower than in men, to facilitate childbirth.

Detailed anatomy of the pelvis

The pelvis is divided into two parts by a plane which extends from the upper margin or promontory of the sacrum to the upper margin of the articulation between the two pubic bones – i.e., the symphysis pubis. On the surface of each coxal bone a line may be traced from the sacral promontory to the symphysis pubis. This is called the iliopectineal line, and it helps to complete the circumference of the plane which divides the pelvis into two parts. The space above this plane lies mostly between the expanded iliac bones. It belongs to the abdomen proper and is known as the false (or lesser) pelvis. The space below the level of the sacral promontory and iliopectineal lines is called the true (or greater) pelvis, and certain descriptive terms are employed in connection with it. Thus the plane which separates it from the false pelvis is called the inlet or brim of the true pelvis. Its inferior circumference or outlet extends from the tip of the coccyx to the inferior border of the pubic symphysis, and from the one ischial tuberosity to the other.

Between the ischial tuberosities in front and extending forwards to the symphysis there is the subpubic arch. The space between the inlet and the outlet is named the cavity of the true pelvis. the measurements of the true pelvis are made along certain definite lines which are applicable to the brim, the cavity, or the outlet. These are (1) the anteroposterior or conjugate diameter – i.e., from the medial line in front to the medial line behind; (2) the transverse or widest diameter; (3) the oblique diameters – right and left. These extend from the articulation between sacrum and ilium on one side to the farthest point on the opposite side of the medial plane. In the erect attitude of the body the plane of the brim of the true pelvis forms an angle with the horizontal that varies from 60° to 65°. Thus the weight of the upper part of the body, which is communicated to the sacrum is directed downwards and transmitted through the innominate bones to the heads of the femora, and so the inferior extremities.

In addition to the ligaments, muscles, blood vessels, and nerves which constitute the soft parts of the pelvis, there are certain organs, including the urinary bladder and rectum, that are present in both sexes, and others that are peculiar to each sex. The urinary bladder is located behind the symphysis pubis, and only rises out of the pelvis into the abdomen when considerably distended. The rectum, i.e. that part of the gastrointestinal tract which passes through the pelvis, lies on the front of the sacrum and coccyx, a short distance below which it terminates in the anus. The lower end of the rectum is supported by two muscles – the levatores ani – which surround it so completely as to form a floor or diaphragm for the pelvis.

Differences between the male and female pelvis

In the male there are also the vesiculae seminales and the prostate gland – the latter surrounding the outlet of the urinary bladder. In the female there are the uterus, ovaries, and their various appendages. The diverse functions of these organs have led to corresponding and well-marked differences in the size and form of the osseous pelves of the sexes. In the female the bones are more slender, and the muscular impressions less distinct. The true pelvis has a greater breadth and capacity, but its perpendicular depth is less. The inlet is more nearly circular; the ischial tuberosities are wider apart, and the subpubic arch is much wider. All of these differences indicate special modifications in connection with the necessities of childbirth. Although the depth of the cavity of the true pelvis steadily increases from childhood to puberty, the characteristics of the sexes are discernible even at birth.