ancient libraries

Figure 1. Part of a Greek astronomical papyrus written in Egypt between the fourth and 2nd century BC. Greeks built many libraries to house their records and other writings. The greatest of these was at Alexandria, the city founded in Egypt by Alexander the Great, which contained half a million parchment and papyrus transcriptions.

Figure 2. Students at New College, Oxford, England, listening to a lecture in about 1453. Many medieval universities had large libraries, but the books were normally used only by the dons (tutors); the students took notes.

Figure 3. Students at New College, Oxford, England, listening to a lecture in about 1453. Many medieval universities had large libraries, but the books were normally used only by the dons (tutors); the students took notes.

Nowadays we take libraries for granted. We are accustomed to their existence, and most of us have access to a library of one kind or another. It is a curious fact that some very early libraries were like modern public libraries in that they were open to everyone. Yet in the centuries in between, the library became an amenity that was restricted to a wealthy and educated minority. It was not until the modern idea of the public library had evolved that ordinary people could again enjoy the services of a library.

The earliest library was really an archive. In ancient Egypt, which was one of the first countries to develop writing, there were two kinds of library. One was the government archive, which contained records of rulers, taxation, administration, and so on; the other kind was the religious or temple library of sacred writings. In both kinds of library, the records were written on papyrus rolls and stored in clay jars. In the Mesopotamian kingdoms of Babylonia and Assyria records were made on baked clay. From the evidence of the thousands of such "books" that have survived, it seems that as far back as 3000 BC there were public and private libraries containing works on a great variety of subjects including medicine and astronomy.

During the great age of Greek civilization in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, each city-state had its own library, but little is known about them. It was the first of the Greek rulers of Egypt, Ptolemy I, who founded the great library of Alexandria in the last years of the 4th century BC. It was called the Museum, or home of the Muses (the deities of art and learning and the daughters of Memory), and this is the first use of a word that we now apply to collections of things other than books. The Alexandrian library was the greatest in the ancient world. It was properly catalogued and contained half a million manuscripts. It was destroyed in AD 391 by order of the Roman emperor Theodosius, a Christian, who aimed to stamp out pagan learning and belief; with this destruction went much of the accumulated knowledge of the ancient world including, for example, one of the books of Euclid's geometry.

The Romans took from colonies like Greece not only the idea of libraries, but the books themselves. In the first century BC the Roman scholar Lucullus threw his own library open to other scholars. Later, emperors founded public libraries, so that by the middle of the 4th century AD there were 29 libraries in Rome alone. Anyone, from nobleman to slave, could use them. Another library, founded in the fourth century at Constantinople, grew in 300 years to be what was then probably the greatest library in the world; but it was rivaled by those founded in the 7th to 9th centuries by the Moslems. In Baghdad, for instance, a huge library was opened and made available to the public, and in Cordova, Spain, there was a library of 600,000 books, including many scientific works.

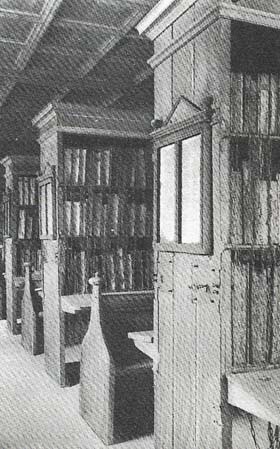

In Europe, during the centuries that followed the fall of Rome in AD 476 (the so-called Dark Ages), books and libraries became something that only the literate few could enjoy. The more significant developments, from the point of view of the preservation of works of literature through the Dark Ages, were those that took place in the libraries of the Christian communities, and particularly in the Benedictine monasteries. It was in these monasteries that the obligation to preserve and reproduce manuscripts was most faithfully carried out. But as medieval universities began to develop as a result of the Renaissance, the demand for books also grew. In northern Italy (where universities grew out of the law schools at Bologna and Padua) and at Paris, it was at first only the masters who had collections of books. But in time each college built up its own library. In 1322 the Sorbonne had a collection of over a thousand books; the most important ones were chained and only the lesser ones were allowed to circulate. There were other university libraries at Prague, Salamanca, Oxford, and Cambridge, but at each one the books could be borrowed only by senior members of the university.

|

| Chained library in Hereford Cathedral, England. Books were chained to prevent pilfering by the scholars and students, many of whom were so poor that they could afford to buy the expensive volumes only one page at a time. |

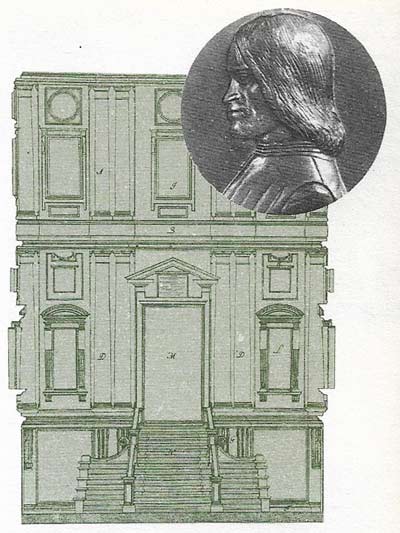

As well as the monastic and university libraries, there were a few private collections made by wealthy families. The Medici of Florence gave from their own library, in 1444, enough books to start a public library, known as the Medicean Library. Later they founded the Laurentian Library. But these were very rare occurrences. In any case, so few people could read that public libraries for the use and benefit of ordinary people would have served little purpose. Until the invention of printing in Europe in the middle of the 15th century, a book remained a rare and precious possession.

The invention of printing meant that books could be produced quickly, cheaply, and in large numbers. Very soon after its invention many literary works in Hebrew, Latin, Greek, and the languages of Western Europe became available. These books could be put on open shelves instead of being chained to lecterns or locked in chests. Above all they could be loaned. Books were more easily available; more people could learn to read; and the demand for books grew accordingly, so that by the end of the 16th century conditions were once again ripe for the idea of libraries for general use.