European society 1250–1450

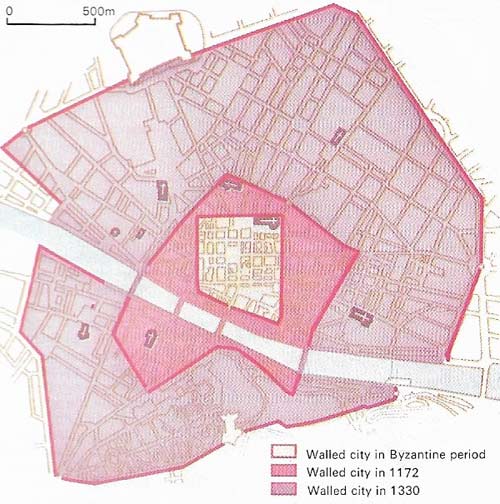

Figure 1. The fortified Roman town of Florence was reduced during the stagnation of the Dark Ages but grew rapidly in the 12th and 13th centuries. Its expanding size and power were marked by the wider walls of 1172 and 1284–1330. In spite of internal factional struggles the city's position as a center of cloth-making and the wool trade led to an era of prosperity and cultural achievement, particularly after the rise of the Medici merchant family in the early 1400s. Florentine bankers were the most influential in Europe and the florin, minted in the thirteenth century, became a monetary standard.

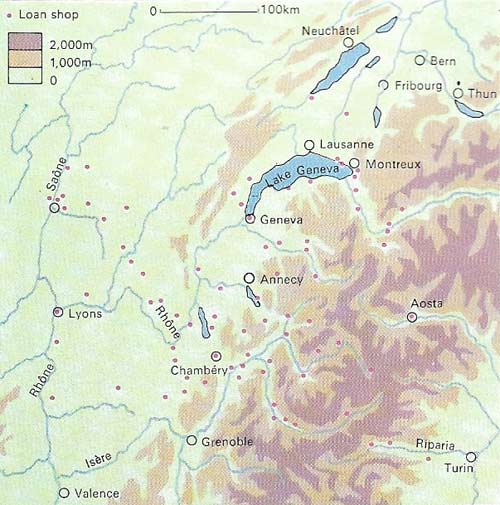

Figure 2. Loan shops or Castaneda of Lombard moneylenders were a feature of the alpine valleys of Savoy in the 13th century. In many parts of Europe country life was transformed by money at this time, especially in Italy. The rise in the population made necessary the rapid development of different soils. Peasants obtained the required capital to a large extent from loans. Moneylenders operated from shops set up in rural areas.

Figure 3. Venice at the time of Marco Polo's departure for Asia in 1271 (depicted imaginatively in this book illustration) was the busiest port in the world. The city was also a center of shipbuilding and a leader in ship design.

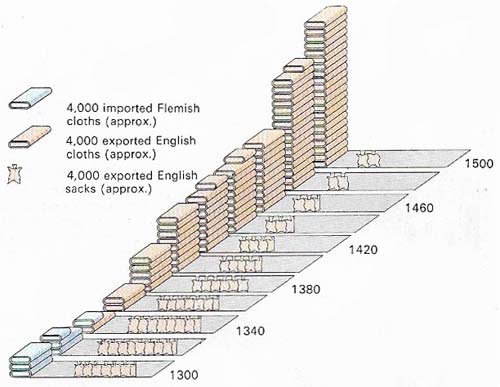

Fig 4. The English wool trade expanded rapidly after 1200. Raw wool was at first sent for processing to the established cloth makers of Bruges, Florence and other centers in France, Flanders and Italy but their monopoly was broken by the growing export of English-made cloths.

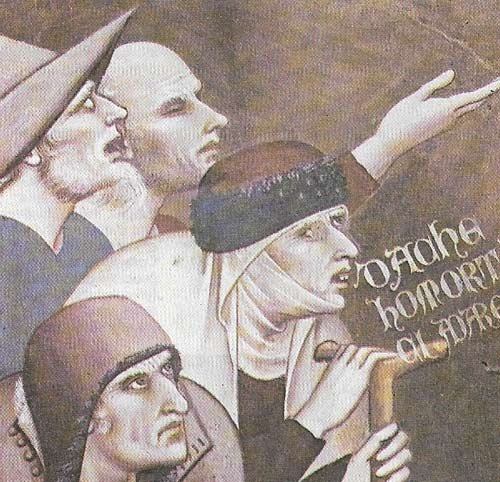

Figure 5. "The Triumph of Death" by Andrea Orcagna (c. 1308–1368) was painted shortly after the Black Death of 1348. It depicts with terrifying realism the sufferings of the sick who beg to be released from the torments of plague. The theme of death and the instability of human fortune pervades the literature and art of the later fourteenth century and it is likely that this was an effect of the dramatic carnage of the plague. "No one wept for the dead", wrote a Sienese chronicler, Agnolo di Tura, "because everyone expected death himself". Survivors surveyed their shrunken world in a sombre mood.

Figure 6. The Jacquerie, a peasant rising which engulfed the Paris region in 1358, resulted from the disorder in France after the English captured King John II in 1356. The main grievance arose from attempts by landowners to keep down wages in a time of labour scarcity. All the fourteenth-century peasant rebellions had broadly similar causes.

Figure 7. The shepherds in "Nativity" by by Hugo van der Goes (c. 1440–1482), was clearly drawn from peasant life, show a marked individuality characteristic of the confident peasant culture of the age and exemplified also in the popular art of the woodcut. Compared with the animal skins of three centuries earlier, the clothes worn here are luxurious.

By 1250, the material basis of Europe as it is now known was established; most of the towns and villages that exist today were already inhabited. Although forests were more extensive than now, the area under cultivation had passed the period of most rapid expansion. The next 200 years were characterized by crises of population and production, alternating boom and slump, and by the development of the techniques of finance (3), business and trade. The underlying crisis was probably the high population of the 13th century. Tax records show that in southern England and Provence the number of inhabitants doubled during the century. Older towns such as Florence (2) pushed out beyond their walls and multiplied their parish churches, while new towns were founded in every part of Europe.

|

| Coins proliferated in the late Middle Ages with the development of economies based on trading. A gold coinage, almost unknown since the 7th century, was restored in the 13th. Pioneers of the new money were the republics of Venice with the ducat and Florence with the florin. These coins are roughly standard appearance and were issued in 1357–1367 by Pedro I of Castile (A); in 1399–1413 by Henry IV of England (B); in 1419–1434 by Conrad III of Mainz (C); in 1368 by the republic of Florence (D); in 1350–1364 by John II of France (E); and in about 1420 by Tommaso Mocenigo representing the Venetian republic (F). |

The increase in urban populations

In 1250 the population of Europe had reached about 70 million and evidence from several sources suggests that the rate of increase was about one per cent a year. In consequence the food resources of the continent were stretched. Migration from Germany into central and eastern Europe reached its height in the 13th century, while the poor soils and marginal lands of the alpine and Apennine uplands came under the plow for the first time. A higher expectation of life combined with a higher birth-rate to push European society into a slowly maturing demographic crisis.

|

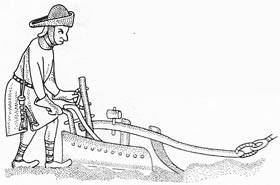

| This twelfth-century plough, shown in a medieval manuscript of Gregory the Great's Moralia on Job, has a realistic look with its wheeled fore part and mould board to follow the cut and turn over the sods. The mold board and coulter (cutter) were fixed to a beam drawn by oxen. The design and function of farm implements changed little before the sixteenth century. |

This process created new social forms, above all the large towns that profoundly modified European civilization. Since classical times, probably no town with more than 40,000 inhabitants had existed; now Venice Naples, Barcelona, Bruges, Paris and some others far exceeded this limit. Immigrants, often from distant places, crowded into them, to work in the textiles of Bruges or Florence, or the more diversified trades of London and Paris. Two great ports, Venice and Genoa, provided Europe with the products of the East, and among the first Europeans to visit China was the Venetian merchant Marco Polo. The Baltic trade was monopolized by the Hanse – a powerful league of North German cities.

In the urban centres, more specialized ways of life could develop. The skills of the accountant and the banker (developed first in Pisa and Florence and the practice of marine insurance (a Venetian speciality) made possible the first international companies; the Bardi of Florence, through their agents in London and Bruges, were the greatest creditors of the English crown, for instance. Courtiers, civic patrons of art and people of fashion flourished in the midst of a new, degrading poverty. The friars adapted religion for the urban masses, while poverty and disease were mitigated by burgeoning charities. Whatever the crises, the great cities continued to grow.

A century of catastrophe

Undernourishment left the teeming population of the 13th century a prey to a worsening climate, hunger and disease. In 1315 persistent rain inaugurated a series of harvest failures and two years of famine throughout northern Europe. The high prices and booming business of the previous century now proved unstable; the economy had advanced too fast. The boldest venturers, the Italian bankers, were hit hardest of all and in 1343 repudiation of the English royal debt precipitated a crash in which the house of Bardi and many others collapsed.

In 1348–1350 came the terrible Black Death, the first of the recurrent bubonic and pneumonic plagues that were to beset Europe until the 1730s. Carried by both rats and humans in ships from the Crimea, the plague was immediately fatal and spread rapidly from southern to northern Europe. Its effects were catastrophic: probably about 50 per cent of the total population died, but some towns in Provence lost four-fifths of their inhabitants and many villages were finally deserted. In many parts of Europe there was some recovery, but the plague returned in 1361, 1369, and 1379, and by 1400 the population had shrunk to about a half or two-thirds of its total a century before. This was reflected in the all-pervading theme of death in late medieval art (Figure 5).

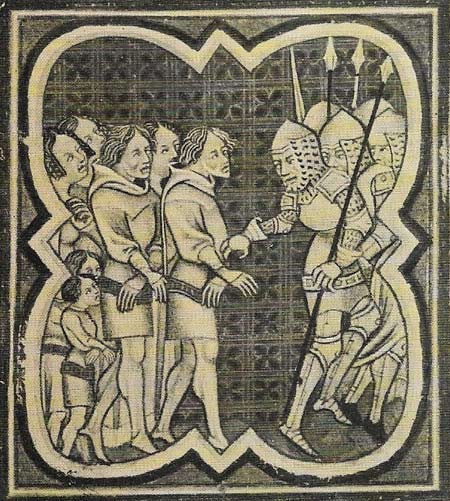

One of the effects of these calamities was social disorder, in towns and in the country. For the first time peasants and townsmen took violent action against bad government, in the Jacquerie rising (Figure 6) of northern France (1358) and peasant rebellions in England (1381) and Catalonia (1409–1413). Governments everywhere were fearful of such movements and tightened their control wherever they could. These revolts were led by men of enterprise, peasants, farmers or artisans who resented the legal limits on their activities. The fall in population led to a demand for labour and labourers demanded the right to sell their services to the highest bidder.

The standard of living

The revolts reflected the rising expectations of the peasantry; in England, wage rates doubled while prices remained stable be-tween 1350 and 1415. They were a sign of the vitality and independence of humbler men (Figure 7); for them, the demographic decline meant a higher standard of living and the opportunity to turn peasant holdings into small farms. After a century of catastrophe, the 15th-century peasant followed the bankers and merchants of the pre-plague age into a measure of prosperity.