early weapons and defense

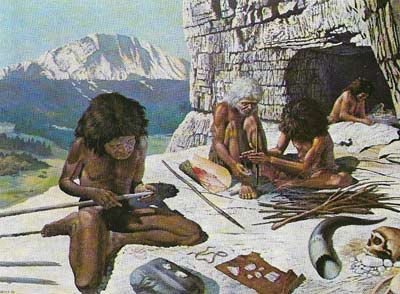

Figure 1. Neanderthal man lived in Europe some 40,000 years ago and represented Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) culture. The weapons of these people were mostly stones, clubs and spears. The spears were merely straight shafts sharpened to a point and hardened by fire. The technical development of weapons did not occur evenly throughout the world but eventually Neanderthal roan's culture was supplanted by more sophisticated cultures using stone-tipped weapons – the Neolithic or New Stone Age peoples. The Australian Aborigines remained at the Paleolithic stage. Stone weapons were superseded by bronze and eventually by iron.

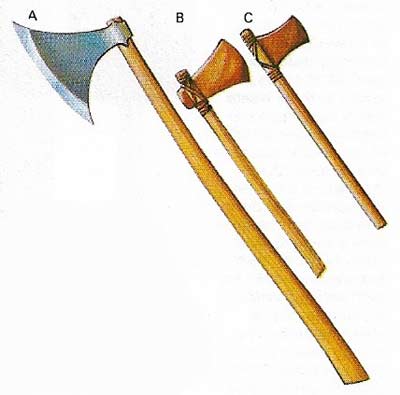

Figure 2. Early axes were quite small. Neolithic (B) and Bronze Age (C) axes measured about 7 centimeters (3 inches) across the blade, compared with 28 centimeters (11 inches) for the Viking axe (A) of the 7th century.

Figure 3. The early spear (A) and javelin (B) used in 650–500 BC were little different from the Frankish-Gothic spears (C, D) and Roman javelin (E) of the 5th–7th centuries AD. The bill (F) was a medieval development of the spear.

Figure 4. Spearheads changed little in their design, despite the different materials – stone, bronze, and iron – from which they were made. Bronze spear heads from Greece (A, B) made in about 700 BC resemble the later iron ones of the Celts (D), Vikings (E), and Saxons (F). Broad-headed stabbing spears, such as the Macedonian example (C), often had a collar or flange to prevent the spear from being pushed right through the victim's body.

Figure 5. The medieval knight (A) was a product of the arms race between more effective armor and improved arrows. More vulnerable than a man, the horse also had its own armor; but if the knight was unseated, as often happened, he found it hard to remount and use his weapons, and was at the mercy of any nearby foot soldier less heavily encumbered. With the introduction of firearms, against which armor offered little protection, armor declined in use. The lance was the knight's primary weapon, but if this broke he still had a variety of other weapons (B) to use. Most knights carried a war sword (3) with a decorated scabbard and belt (4). But other popular weapons included a mace (2) and a battleaxe. The war hammer (1) was a direct development of the earlier battleaxe.

Figure 6. Three distinct types of bow each had their place in the history of arms development. The eastern re-curved bow (A), nearly 4,000 years old, was the kind used by the Mongol hordes. The wind-lass or Genoese crossbow (B) proved ineffectual against the superior English longbow (C).

![Primitive swords include the Egyptian sickle sword (A) of 2000 BC and a Swiss sword in bronze (B), 1,000 years later. The Greeks used a double-edged stabbing sword (C) and a single-edged cutting sword (D). The single-edged falchion [E] dates from medieval times. The straight double-edged sword [F] was a cutting weapon. The later rapier (G) was used with only the point. The cavalry sword (H) and Samurai (I) were slashing swords.](../../images15/swords.jpg)

Figure 7. Primitive swords include the Egyptian sickle sword (A) of 2000 BC and a Swiss sword in bronze (B), 1,000 years later. The Greeks used a double-edged stabbing sword (C) and a single-edged cutting sword (D). The single-edged falchion [E] dates from medieval times. The straight double-edged sword [F] was a cutting weapon. The later rapier (G) was used with only the point. The cavalry sword (H) and Samurai (I) were slashing swords.

Figure 8. A large shield and short-sword were standard equipment for the Roman legionary. The shield provided a defensive wall behind which the soldier was safe from almost all enemy weapons. In deep formations shields could be used to form a roof and walls known as the testudo or tortoise. In this way soldiers could attack the walls and gates of fortifications virtually with impunity. A short-sword lacked the reach of a longer weapon and was probably used with a stabbing action. But it was also less cumbersome and less fatiguing to use than a long-sword. A helmet and breastplate helped to protect the body from blows that passed the shield.

To provide himself with food and protection, man has always needed weapons. Primitive man probably armed himself with sticks and stones that he found lying around (Figure 1). These handheld weapons were adequate at close range but were obviously no use for beating off a large predatory beast or bringing down an animal such as a fleet-footed antelope. With an increase in manual dexterity and intelligence, man began to adapt the materials at hand to make tools and weapons.

|

| The use of worked stone for arrow and spearheads increased the penetrating power of such weapons. This dates from the Middle Stone Age (about 16,000 BC) and was found in Europe. |

The first weapons

A curved stick, carved to the correct cross-section, can be thrown with great accuracy and will return if it misses its target. This weapon – the boomerang – is still used today by Australian Aborigines.

Stones with a groove carved round them and tied together by a length of leather or cord produce a bolas, a throwing implement still used in South America. This weapon also has a long history and similarly shaped stones have been found in Stone Age sites in Europe. Such weapons are good enough for hunting game, but man needed better weapons and the techniques for using them in order to overcome his fellow men.

|

| The war club or mace grew gradually more formidable. The 2,000-year-old iron mace (B) resembles a 4,000-year-old Egyptian wooden mace (A) but was less likely to break. The fluted head of a 14th-century mace (C) had much more crushing power. |

The spear (Figures 3 and 4) has been used for thousands of years as both an offensive and a defensive weapon. Originally it was merely a straight stick with a fire-hardened point. With the gradual improvement of weapon-making techniques it was successively tipped with stone, bone, bronze and eventually iron.

Once a spear had been thrown or an opponent had managed to get through the defense, a more convenient weapon was needed for hand-to-hand fighting. Zulu warriors solved this problem with a short-handled, long-bladed stabbing spear called an assegai. Other peoples arrived at a slightly different solution with the sword (9), although there is little evidence of when or where it originated.

At first, swords were made of bronze and subsequently of iron. The Greek armies needed special swords for cutting as well as short weapons for stabbing. The Romans (Figure 8) fought with an short iron sword – the gladius. Wielded from behind a barrier of large shields the gladius enabled the Roman legions to rule most of the known world for about 400 years. The heavy infantry of Rome was eventually overcome by the lightly armed cavalry of the barbarian hordes. With the collapse of the Roman Empire the Roman way of fighting disappeared almost completely.

From their bases in Scandinavia came the "sea-wolves" in their longships. Vikings dealt death and destruction with their long-bladed swords and battleaxes. Resistance to them produced organized armies whose soldiers were armed not only with long-sword and battle axe but also with the bow. Their discipline beat the loosely organized Vikings.

Bows and arrows

The bow (Figure 6) used in Europe was a much heavier weapon than the light recurved bow of the Eastern Steppes (made of laminated horn and wood and small enough to be fired from horseback). Not much used in the west for warfare, it was a hunting bow designed for use on the ground and from covet. Its ultimate form was the English longbow – 1.83 meters (6 feet) of yew with a horsehair bowstring capable of loosing an arrow 1 meter (39 inches) long. 'The Norman troops of William the Conqueror, who in 1066 invaded England, carried bows and each was also armed with a shield and sword and they wore long corselets of mail.

Later arms and armor

Mail became standard equipment, at least for those who could afford it, and gave some protection from arrows. But it did not prevent the wearer from being bruised by blows aimed at him. As armor developed, small plates were introduced into the mail at vulnerable points until eventually a knight was completely encased in steel. The mounts, which resembled great lumbering cart-horses, also had their own armor.

On their mighty chargers the knights thundered into battle – although somewhat slowly with the weight they were carrying – equipped with a variety of death-dealing weapons. A 3.7 meters (12 feet) lance of ash, tipped with iron, a shield and a long-sword were standard equipment. Other weapons included a short dagger and often a mace and battle axe or morning star.

Swords of this period were generally long, double-edged and straight with a reach of about 2 meters (6 feet). They could be used with one or both hands. The age of chivalry came to an end with the success of the English longbow at the battles of Crecy (1346) and Agincourt (1415). The bow's rapid delivery, accuracy and range defeated the knights and demoralized foot soldiers. Opposing the longbows were Genoese crossbows that could be operated by untrained troops and did not require the practice needed to use the longbow. Their arrows could also penetrate armor. But although a more useful weapon in these respects, the crossbow had a short range and a low rate of fire and was therefore no match for the longbow.

Swords became narrow and light, with large guards to envelop and protect the hand. By the 18th century they had become very light and fairly short, often with decorated hilts. Horsemen favored curved swords, which were used until the present century. In modern times foot soldiers carry bayonets instead of swords, which are now used almost exclusively for ceremony.