exploration and trade in Tudor England

Figure 1. John Cabot and his son Sebastian discovered Nova Scotia off the North American coast in 1497, but believed that they had found Asia. John died on another voyage a few years later. In 1509 Sebastian sailed past southern Greenland into the Davis Strait, and may have gone as far as Hudson Bay. He later went to Spain and spent many years as pilot-major to the mercantile marine, making explorations of the South American coast. He returned to England in 1547, and helped to form a joint-stock company in 1553 to search for a northeastern passage. This company sponsored the expedition of Willoughby and Chancellor to Moscow.

Figure 2. Martin Frobisher claimed to have found the elusive Northwest Passage in 1576, and a Cathay Company was set up to develop trade with China. The following year he thought he had discovered gold, and found backers for a new voyage to Greenland, almost unknown since the Viking voyages of the 10th century. He took some Eskimos, with whom he is shown fighting here, back to London, but the English climate killed them.

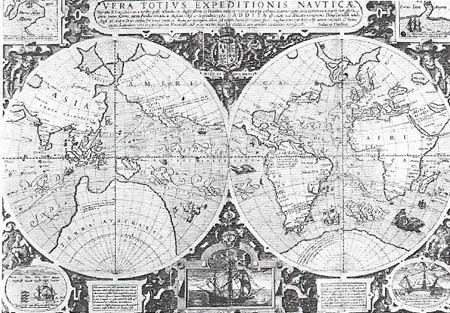

Figure 3. Navigational aids were vital for the success of ocean-going voyages and many navigation schools, such as Gresham College, were set up in Elizabeth's reign to teach sailors the new skills. These were as important to fishermen as to explorers. As well as the astrolabe, developed by the Portuguese from Arab designs, but which was much easier to use on land than on a ship pitching at sea, revolutionary innovations include Mercator's world map of 1569. Its projection allowed a compass course to be plotted as a straight line on a map. Another was John Davis's backstaff, which modified the cross-staff.

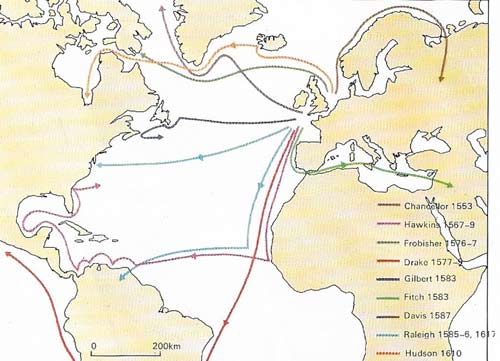

Figure 4. English exploration did not get fully under way until after 1550. Thereafter the main purpose of the voyages was to find a route to the lucrative markets of China and Southeast Asia without infringing on the Spanish and Portuguese possessions that had been apportioned by papal bull in 1493. Thus the merchant companies such as the Muscovy Company sought to find new markets for English cloth in exchange for timber and other goods useful for the shipping industry rather than to establish colonies. Few other expeditions proved as profitable to English industry although raw materials brought home included tobacco, potatoes, and many minerals. But the hope for the Cathay market was never realized and home industry did not profit from the American colonies until the mid-17th century. It was not until 1583 that Humphrey Gilbert attempted to set up the first permanent colony in the New World, in Newfoundland, but his expedition was destroyed by storms.

Figure 5. John Hawkins was the pioneer of the slave triangle that became the basis of English prosperity in the 18th century. He later became treasurer of the navy and introduced many innovations in the design and manning of the ships.

Figure 6. During his circumnavigation of the globe Drake crossed the Pacific from California to the Spice Islands. There he received a great welcome from the natives of the Moluccas, and took aboard three tons of cloves. He also made an agreement with the Sultan of Ternate for future supplies of spices which were so highly valued that Drake preferred them to jewels.

Figure 7. The first settlements of Virginia were failures, conceived of as a means to tap the vast resources of North America for England and to provide a safe market for English cloth, they were organized by Walter Raleigh (who never went to Virginia himself) and were commanded by Richard Grenville (c. 1543–1591). Two expeditions – in 1585 and 1587 – were sent and established on Roanoke Island, but, as a result of the climatic extremes and Indian hostility, the first returned home with Drake after one winter and the second disappeared without trace. Each comprised more than 100 men and women, but Francis Bacon called them "the scum of people and wicked condemned men".

Figure 8. Francis Drake captured a Spanish ship in March 1579 in the Pacific Ocean, in the course of his voyage round the world, and thereby ensured the financial success of his trip. Sixteenth-century Spain depended on large shipments of gold and silver from the New World and their capture could be seen as a contributions to the defense of England and the Protestant faith, the expeditions also took home raw materials.

The sea-captains of the age of Elizabeth (1533–1603) – Drake, Raleigh, and Hawkins – provide probably the most enduring myths of Tudor England, but their exploits were built on a history of exploration that went back nearly a century. The motives to explore were various; but the most important were the economic pressure of a rising population, inflation, and declining traditional markets. So too were sheer inquisitiveness and a thirst for adventure, and a national pride that would not permit England's enemies to enjoy the wealth of the New World unmolested.

The changing pattern of trade

Trade in wool and unfinished woollen cloth was England's vital export in the early 16th century. But in the 1540s the English currency was devalued by debasement and the exchange rate turned against the English exporter. The ancient "wool-staple", or official distribution centre of English wool in Europe, disappeared with the loss of Calais in 1558, and Antwerp itself declined during The Netherlands' long struggle for independence from Spain. The wool industry therefore was seriously affected and capital was diverted to the enclosure of land for improved agriculture rather than pasture, and to the development of coal and other mineral deposits. Traders began to look overseas: merchants hoped to sell cloth to the heathen in undiscovered countries. Exploration was therefore central to economic expansion.

The start of English exploration

The first "English" explorer was an Italian by birth, John Cabot (c. 1450–c. 1500) (Figure 1), who had settled in Bristol. He set out in 1497, commissioned by Henry VII to discover lands not previously known to Christians, to circumvent the papal bull of 1493 that divided between Spain and Portugal all new territories. All subsequent Tudor voyages only acknowledged territory "effectively occupied" in 1493 as related to this bull. Cabot found Nova Scotia and the important cod fisheries of Newfoundland, and suggested a northwestern route to the Spice Islands and the fabled riches of the East that were to delude many future explorers.

Cabot's son Sebastian (1474–1557) unsuccessfully projected a northeastern pas-sage to India, but the expedition of Hugh Willoughby (died 1554) and Richard Chancellor (died 1556) in 1553 took them to Moscow; the Muscovy Company that they set up traded with Russia and established an overland route to Persia. Earlier, in 1509, Sebastian had crossed the Davis Strait, northwest of Newfoundland, and come to Hudson Bay, which he thought to be the Pacific. In three voyages (1576–1578) Martin Frobisher (c. 1535–1594) (Figure 2) reached the same waters; while John Davis (c. 1550–1605) established that Greenland was separate from the mainland and sailed into Baffin's Bay. The Northwest Passage was never free of ice, and so it could not be, as was hoped, complementary to the Cape Horn and Cape of Good Hope routes. The belief in a great southern continent stretching from the south of Cape Horn to the East Indies was also doomed to disappointment. But in search of these far-ranging and often fictional objectives the Elizabethans sailed the known Earth and sometimes beyond it (Figure 4).

Voyages to the Caribbean brought the English into contact with the Spanish Empire. In 1562 John Hawkins (1532–1595) (Figure 5) took African slaves at Sierra Leone and sold them to the Spaniards at San Domingo. A second, similar, voyage in 1564 seemed to have established a profitable commerce, but in 1567–1568 a Spanish fleet caught him at San Juan d'Ulloa and only two of his ships reached England safely. Hawkins then left the sea to reorganize the navy, but Francis Drake (c. 1540–1596), who had been with him at San Juan, returned to the Caribbean and in 1572 sacked Nombre de Dios and captured a treasure-train there.

|

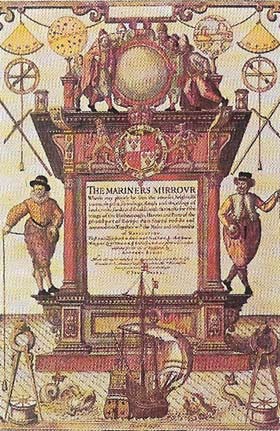

| The Mariner's Mirror (1587) was one of several works on English on geography and navigation dealing with its subject on a scientific, rather than the familiar fanciful, way. |

Later voyages

In 1577 Drake set out in the Golden Hind sponsored by the queen, to find a southwestern route into the Pacific. Sailing through the Magellan Straits, Drake plundered unguarded coastal towns, claimed possession of California, turned west for the Moluccas, and returned home in 1580 via the Cape of Good Hope (Figure 6). In 1586–1588 Thomas Cavendish (1560–15692) became the second Englishman to sail round the world.

Anthony Jenkinson (died 1611) traded in central Asia, Ralph Fitch (fl. 1583–1611) traded with Akbar, the great Mogul ruler of India, and James Lancaster (c. 1550–1618) returned with booty from the East Indies. From such individual enterprises companies were formed to exploit the commercial gains, notably the East India Company (1600). But colonization to establish permanent settlements, rather than trading posts, grew more slowly. Its motives were commercial, to obtain markets and raw materials; political, to weaken Spain; religious, to spread God's word; and social, to re-settle the unemployed. Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539–1583) died on a voyage to colonize Newfoundland, and his half-brother Walter Raleigh (c. 1552–1618) was imprisoned in the Tower of London before his settlement of Virginia took root (Figure 7). Seduced by legends of fantastic wealth, Raleigh sailed to the Spanish Main (northern South America) in 1595, and the failure of a second expedition in 1617–1618 to find Eldorado, the mythical golden city of the Incas, resulted in his execution.

|

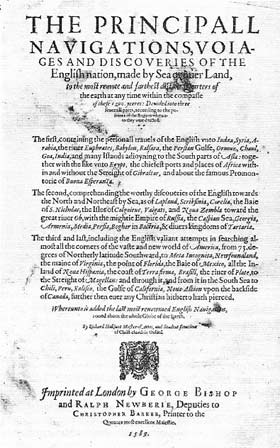

| Richard Hakluyt the younger (c. 1552–1616) was a clergyman who, taunted in France that the English had achieved little in exploration, wrote Principall Navigations (1589–1600) to vindicate his countrymen by writing a detailed record of their voyages. Earlier he had written pamphlets to encourage settlers to go to Virginia, but it was hard to persuade investors to become involved in the new colonies, in which profits took far longer to accrue than in privateering expeditions. The joint-stock companies that were the usual form of investment meant that traders sought profits from single trips, not long-term advantages, but by 1600 permanent control of the East Indian trade seemed desirable. |