Hammurabi

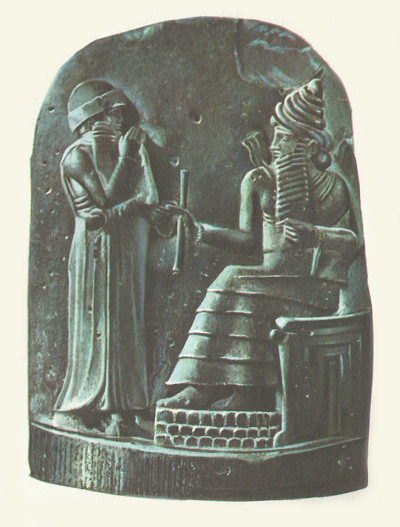

Hammurabi receiving his laws from the Shamash detail from the stele on which they were written.

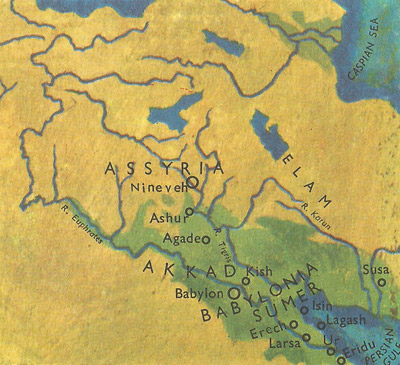

Principal Mesopotamian cities in the days of Hammurabi.

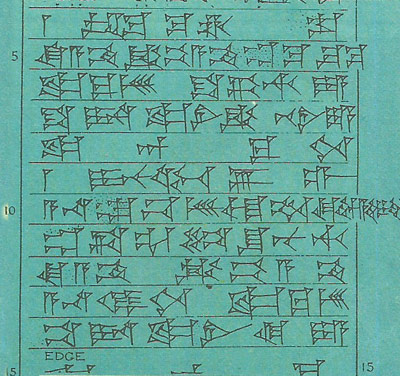

The wedge-shaped or cuneiform writing used in the age of Hammurabi.

Hammurabi seated on his throne.

Hammurabi was the king of Babylonia about 2240 years BC. He expelled the invading Elamites and extended his power so that his realm stretched from the Mediterranean to Susa and from Kurdastan to the Persian Gulf. He built palaces and temples, made great canals and granaries (against famine), but is most famous as a legislator. At the end of the 19th century De Morgan found at Susa a great stele, which when interpreted was found to contain an amazingly well-developed code of laws, in 280 edicts; and these laws seem to have influenced all the legislative systems of the East, including that of the Israelites.

|

| The reverse of the stele of laws

|

Introduction

One of the earliest civilisations began in Mesopotamia, the traditional site of the Garden of Eden. This 'land between the rivers' was so fertile that it attracted settlers far back in antiquity. It was almost certainly over 5,000 years ago that the Sumerians arrived. These people were white-skinned, shaved their heads, and wore shaggy woollen kilts. They came probably from the east, perhaps from the heart of central Asia.

The Sumerians settled in the lower part of the great plain of the Tigris and the Euphrates. They cultivated the land, grew wheat and barley, kept domestic animals, built dykes and ditches, and little temples to their gods.

The arrival of the Semites in Mesopotamia

Many thousands of years ago a race of people came to the plain of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and settled to the north of the Sumerians. They were Semites, who came probably from the Mediterranean coast to the west. They were dark-skinned, wore their black hair long, and the men grew beards. Their part of the country was known as Akkad, and there were numerous conflicts between the Sumerians in the south and the Semites in the North.

These peoples gradually developed from dwellers in collections of primitive mud huts into 'citizens', and several cities grew up, each of which had a temple, a palace, and a priest-king. It was in these cities that the great Mesopotamian civilisation was born. Manufactured goods were bought and sold, traders travelled far afield, systems of law and authority were evolved, and a form of writing invented.

Over the centuries first one and then another city would rise and fall in importance. The greatest of them were Erech, Lagash, Isin, Larsa, and Ur in Sumeria; and Kish and Agade in Akkad. While these cities were having their moments of glory, another tribe came in from the desert and settled. They were the Amorites, a branch of the Semites, and they were the ancestors of one of the most illustrious kings of antiquity, King Hammurabi.

It was probably about 2220 BC that Hammurabi's ancestors established themselves in the insignificant village of Babylon, on the river Euphrates. Gradually Babylon grew in size and importance until it was the greatest city in the northern part of the plain. It was Hammurabi who made it the capital of both Sumer and Akkad, and so brought the great Babylonian empire, and the word 'Babylonia', into history.

Hammurabi, the sixth king of his dynasty, came to the throne probably in 2067 BC. He inherited a war with the powerful King of Larsa. Rim-Sin, and it was not until the thirtieth year of his reign that he defeated Larsa and captured Rim-Sin. From then on he was acknowledged as King of Babylonia. Hammurabi was a great warrior. He controlled the fierce Elamites and confined them to their mountains in the east, and also raided the Assyrian country in the north of Mesopotamia. But his name rests more on his achievements as a man of peace than as a man of war.

Hammurabi was a deeply religious man and built many gorgeous temples. He gained the support of the priests and gave money for religious purposes to Kish, Larsa, Lagash, Ur, Erech, and in the far north, Nineveh, as well as to Babylon. In addition, he raised Babylon's local god, Murduk, to the most honoured place among the empire's gods, and so safeguarded Babylon's primary position in ancient Mesopotamia.

Hammurabi also kept a close watch on the royal finances, food supplies to Babylon from the provinces, clothing for slaves, shipping, and the general welfare of the workers.

But it is for none of these things that Hammurabi's name is mainly remembered today. Instead, it is for something which was found during momentous excavations at Susa in 1901 and 1902. This was his code of laws, found written on an upright slab (or stele) made.of black basalt, measuring 7 feet 4 inches high by 2 feet in diameter. It was found in three pieces which were fitted together, and it is today in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

It is said that this stele was set up by Hammurabi at Murduk's temple in Babylon so that all might consult it. There it remained for at least a thousand years until it was removed by the King of Elam. Then it must have become buried during some siege or conquest, until French archaeologists rediscovered it at the beginning of this century.

On the front of the stele is a picture of Hammurabi receiving the laws from Shamash, god of justice in heaven and earth. Below this are 16 columns or writing - five less than there were originally. These were probably scraped off by the King of Elam where he intended to inscribe his own laws. On the back of the stele are a further 28 columns of writing. The laws are not given in any sort of order and were codified rather than invented by Hammurabi. There are no fewer than 282 of them. The first concerns a man who has 'laid a curse' upon another. The last decrees that if a slave says to his master, 'I am not your slave', he shall have his ear cut off. In between are laws dealing with divorce, trade, medical practices, and violence. For example: 'If a man has knocked out the teeth of a man of equal rank, his own teeth shall be knocked out.' Miscellaneous laws include: 'If a mad bull meet a man in the highway and gore him, that case has no remedy.'

Hammurabi died after a reign of 43 years. He united Babylonia and extended his rule into the central provinces of the Tigris and Euphrates. His achievements made Babylon the center of political and intellectual thought in western Asia, right down until the Christian era.

Hammurabi was interested in every facet of Babylonian life. By wonderful chance, many of his letters (written on small tablets of baked clay) have been discovered intact during recent excavations and are now in the major museums of Europe. Several of these deal with canals – for exapmple: 'Unto Sin-Idinnam (possibly the governor of Larsa) say: "Thus saith Hammurabi: thou shalt call out the men who hold land along the banks of the Damanum Canal that they may clear it out. Within the present month shall they complete the work of clearing out the Damanum Canal."' Hammurabi dug the enormous canal called 'Hammurabi, the abundance of the people', boasting: 'I dug a canal which bringeth copious water to the lands of Sumer and Akkad. Its banks on both sides I turned into meadow, I heaped up piles of grain, I provided unfailing water for the lands of Sumer and Akkad. I gathered the scattered people of Sumer and Akkad; with pasturage and watering I provided them. I pastured them with plenty and abundance and settled them in peaceful dwellings.'