King John (1166–1216)

King John, sullen and resentful, attaches the Great Seal to Magna Carta.

King John, the third Plantagenet King.

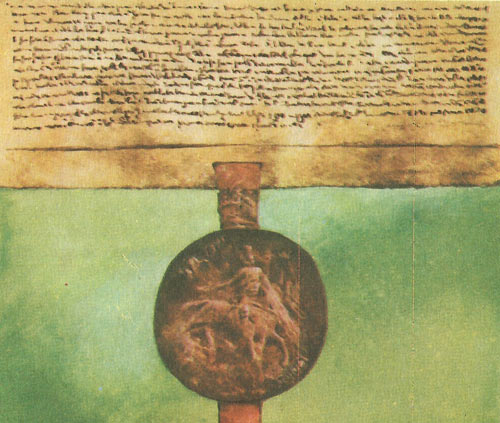

The last part of Magna Carta showing the imprint of the Seal on the wax.

Very few British kings have earned for themselves such an evil reputation as King John. His wickedness has been described in numerous history books, and it has been the custom to hold him up as an example of a really bad king. Recently, however, historians have been more kind to him and, while acknowledging his faults, have shown that there was also a better side to his character. Certainly his faults were very obvious. He had a violent temper and ferocious temper which was liable to blaze out at any moment. It was reported that sometimes 'his eyes darted fire and his countenance became livid'. Convulsed with rage he would roll on the floor, gnawing the rushes, which served in those days as a carpet.

It is also certain that he could be horrifyingly cruel. Not only did he cause many people, including his own nephew, to be put to death, but the execution was usually carried out in a particularly gruesome and revolting way. It is said that he took great pleasure in watching prisoners being tortured. Mercy was a thing he hardly ever showed: on one occasion he had no compunction in ordering the hanging of 28 boys whom he had taken as hostages.

In addition to being violent and cruel, John was also treacherous and deceitful. He rebelled against both his father, who was devoted to him, and his elder brother, who had treated him very generously. Moreover in Magna Carta he made certain solemn promises which he had no intention of keeping.

Today these are the things which shock one most about King John, but in his own time people were even more shocked by his irreligion and lack of piety. He robbed the Church of its property and openly mocked its rites and ceremonies; at the most sacred moment of the coronation service he cracked some coarse joke and roared with laughter.

These then are the sins that have given John his reputation. However, it must be said that he was no weakling. He had great courage. For 17 years, despite powerful opposition from the Pope, the King of France and his own barons, he held onto his throne with great tenacity.

Early life

John was the youngest son of Henry II. He had three elder brothers and at the time of his birth it seemed most unlikely that he would ever become king. In fact his father had already divided up his huge kingdom (which included a large part of France) among his elder sons, and John had been left out – hence his nickname of Lackland. However, in 1183 when John was fifteen his eldest brother Henry died, and three years later his brother Geoffrey was killed in a tournament. Now only his second brother Richard remained between him and the throne.

At an early age John was sent by his father to be governor of Ireland, but this was not a success. At one moment he would be bursting forth into a childish rage and at the next he would be roaring with laughter and making fun of the Irish chieftains – it was said that he even pulled at their beards.

In 1189 Henry II died: he was one of the ablest and most powerful of all English Kings, but his life ended in tragedy. His quarrel with Becket had brought disaster and he had been deserted by his family. John was his favourite son and when he too turned against him, it was said to have broken his heart. He was succeeded by his son Richard, who is often known as Coeur de Lion. His reign was destined to last ten years, but of that time he only spent a few months in England. The rest of the time was taken up with foreign wars and the Third Crusade.

John becomes king

In 1099 Richard was killed and John's way to the throne was almost clear – almost but not entirely. For his brother Geoffrey had left a son, Arthur, who was 16 years old, and who by right of birth should have become king. However, in those days this did not always apply, and in England John was generally accepted. In France, however, there was great support for Arthur and fighting broke out.

At first John had some success: Arthur was captured and ruthlessly put to death in sinister and mysterious circumstances. But the war still continued and by 1204 the French had succeeded in driving the English out of Normandy; this had been joined to England since the time of William the Conqueror some 150 years before. To John this was a bitter blow and he was determined that he would win Normandy back. But other troubles interposed.

Quarrel with the Pope

In the Middle Ages the most powerful institution in the country was the Church. Henry 11 had been the strongest king of his time, but when he had tried to interfere with the power of the Church, he had been thwarted and humiliated. In defiance of this warning John now became involved in a bitter struggle with the Church and Pope. The point at issue was the election of a new Archbishop of Canterbury. John wanted one man (John de Grey) and the Pop e wanted another (Stephen Langton). Pope Innocent III was a man of great determination and when Jon flatly refused to allow Langton into the country, he took the drastic step of placing England under an Interdict. This meant that all the churches had to close and no proper services could be held: the dead were buried in unconsecrated ground and marriages had to take place in the church porch.

The Pope thought that this terrible punishment would be enough to bring John to heel, but this was not the case. John was quite unrepentant and proceeded to confiscate a lot of Church property.

In the next year (1209) the Pope struck again: he declared John excommunicated, that is he expelled him from the Church. This meant that he was doomed to go to Hell; his subjects were freed from allegiance to him and anyone taking arms against him would be blessed as a Crusader. But still Jon refused to yield and this state of affairs lasted for five years.

In 1213 John suddenly decided to yield. His enemies had become too powerful: at home the barons were very discontented, and abroad his old enemy, the king of France, urged on by the Pope, was preparing an invasion of England. John saw that the only way to keep on his throne lay in complete surrender to the Pope. Accordingly John did homage to the Pope and surrendered to him his kingdom, which he received back as a vassal.

This action caused confusion among John's enemies. The French king was ordered by the Pope to withhold his invasion. All Englishmen, including Stephen Langton, were dismayed at the loss of their country's independence; moreover, they were exasperated by the injustices of John and the heavy taxation that he imposed.

Quarrel with the barons

In 1214, John made his long delayed attempt to recapture Normandy, but this ended in defeat and failure. This was clearly the moment for the barons to strike. Under the guidance of Stephen Langton they decided that they would not depose the king but would extract from him a number of promises. These were all contained in a charter which, because of its great length, came to be known as the Great Charter of Magna Carta.

On June 15th 1215, John met the barons at Runnymede. They presented him with their Charter, and John gave orders that the Great Seal of England be attached to it and that it should be issued in his name (it should be noted that he did not sign it). Immediately copies were sent out all over the country. Today in Lincoln and Salisbury cathedrals one can still see the copies that were sent there in 1215; and two other original copies can be seen in the British Museum.

Magna Carta

Magna Carta contains 61 clauses. Many of these are of little importance and deal with details of the feudal system. Others confirmed the freedom of the Church and the privileges of certain towns. The most important one said that no person should be imprisoned, deprived of his property or outlawed except by the law of the land.

Magna Carta has come to be regarded as one of the most important documents in English history. Many people look on it as the most important step in the long struggle of the English people for freedom. And yet it contains nothing revolutionary or even new; it was merely a statement of laws as they existed at that time. It gave no new rights to anyone and the promises it contained applied only to freemen (this meant the barons and a few others). The great mass of the people – villeins and serfs – were not affected by it at all.

Why then is it so important? The reason is that it was the first time that it was stated in writing that there were limitations on the king's powers and that he was bound to keep the law. It established that the subject had certain rights which the king must respect. In later ages when kings became tyrannical and tried to set aside the law, people would appeal to Magna Carta and assert their rights.