Marcus Aurelius to Constantine

The new method of choosing an emperor. The old emperor has died, and the legionaries in a frontier camp acclaim their own general.

Part of the great wall which Aurelian built around Rome.

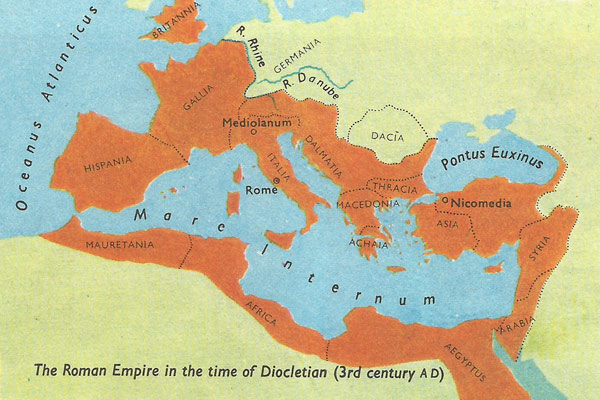

Roman Empire under Diocletian.

Marcus Aurelius, Emperor of Rome between AD 161 and 180, succeeded to an Empire that had enjoyed almost a century of good government and prosperity. But during his reign frontier wars threatened the Empire, and it was ravaged by a great plague. His son, Commodus, who succeeded him, proved another Nero. He was corrupted by power and evil advisers, and became increasingly mad; in 192 he was murdered.

From that year on, the power of the Roman Empire was openly in the hands of the soldiers. Commodus's successor, Pertinax, who tried to restore the authority of the senate and the discipline of the troops, was soon murdered by the Praetorian Guard. The Guard then put the title of emperor up for auction, and sold it to the highest bidder – Didius Julianus, a senator whose only qualification for ruling was his money. Meanwhile on the frontiers the Roman legions acclaimed three other emperors; and out of the struggle which followed, Septimius Severus (193–211) emerged as emperor. But the armies now knew that they could act as kingmakers, and successive emperors were forced to curry favour with them.

Severus's son and successor, Caracalla, was overthrown in 217, and there followed 12 emperors over the next 36 years, not one of whom died a natural death. And in the anarchy of the mid-3rd century it is almost impossible to keep track of the emperors, so many were acclaimed locally in the frontier provinces. With the accession of Claudius Gothicus in 268 some stability returned, but it was not until the drastic reforms of Diocletian that the Empire recovered from the damage of the third century.

Barbarian invasions; financial difficulties

The damage to the Empire was done from outside and from within. Externally, the Empire was troubled more and more by barbarian invasions, which were the major cause of its eventual fall. The Goths invaded the Balkan peninsula and Asia Minor from their base on the lower Danube, and the Franks, Alemanni, and other Germanic tribes, pushed out of their lands in Northern Europe by other migrating tribes, moved southwards in search of new homes. Plundering and burning, they swept through the frontier provinces. Meanwhile, the Empire was under attack in the east from the Persians. The Roman Empire was also being undermined from within by the creeping disease of 'inflation', and the 3rd century was a time of economic chaos. There were many reasons why it was difficult for emperors to raise enough money. The wars against the invading tribes were expensive, and the army had to be enlarged to meet its increasing commitments. Septimius Severus, realising how important the army was - not only because it protected the frontiers but because it could create a new emperor if dissatisfied – increased the soldiers' pay, and Caracalla did the same. All this strained the Empire's resources. Yet there was only one big increase in taxation in all this time, and the complicated and wasteful methods of assessing taxes were not altered until Diocletian's reign.

Instead of reforming the tax system and raising new taxes, the emperors simply devalued the currency, by making more money. Septimius Severus, for instance, reduced the amount of silver in the denarius (the standard silver coin) to 60 per cent, and the emperors followed suit. In about 200 the denarius was almost pure silver; by 300 it was made of bronze with just a thin silver plating. But the emperors could not create more goods for the money to buy. The result of this was that prices rose and the same amount of money bought less and less. The soldiers were encouraged to supplement their pay by looting, and the civil servants by accepting bribes. So chaotic were the Empire's finances that soldiers and civil servants later began to be paid in kind, with wages of corn instead of money. Again, it was left to Diocletian to straighten out the economic muddle.

The one big increase in tax came when Caracalla granted the coveted Roman citizenship to all free men in the Empire in 212. This sounds like an enlightened measure, spreading the privileges of citizenship to loyal subjects, and making Rome 'the common fatherland'. But in fact, by now, many of the privileges of citizenship had disappeared; and since all citizens were liable to tax, it was a convenient way to raise money. In place of the old distinction between citizens and non-citizens there arose a new distinction: the honestiores (nobles) and the humiliores (lower class).

Third century emperors

Septimius Severus was the first emperor to realise how the Empire had changed, and to cater for these changes. He had no time for the senate, which former emperors had at least pretended was the 'partner' of the imperial power. Instead, Septimius appointed soldiers to many of the most important jobs in the Empire. He was the soldiers' emperor; he created new legions, as well as increasing the army's pay and privileges. Septimius died at York after 3 years' campaigning in England and Scotland. With his last breath, it is said, he advised his sons to co-operate with each other and to pay the army well.

Caracalla, the elder son, followed the second piece of advice, but not the first; he soon murdered his brother Geta and became sole emperor. But his reign lasted only six years and was followed by a period of confusion.

A strong emperor was found again in 268 – Claudius, called 'Gothicus' because of his great victories over the Goths, who were plundering the Balkans. Claudius, however, soon died. His successor, Aurelian, continued with the conquest of the invading tribes, and crushed the rebel kingdom of Palmyra in the east, where a woman, Zenobia, held Egypt and Asia Minor in defiance of Rome. Aurelian even tried economic reforms. But the fact that he had to build a wall round the city of Rome is a sad comment on the strength of the Empire in this century of barbarian invasions. After Aurelian's assassination in 275 the pressure of these tribes did not slacken; Probus campaigned against them on the northern frontiers.

Two years after the army killed Probus, Diocletian became emperor. He was the son of a freedman who had risen through the ranks of the army until he became commander of the bodyguard of the Emperor Numerian. When, on the 17 September 284, Numerian was found dead in mysterious circumstances, the young Diocletian was acclaimed in his place. Many emperors had started the same way and had not lasted long. Diocletian was different. He reigned for 20 years, and at the end of that time he laid down the imperial power of his own free will. As a planner and reconstructor he was second only to Augustus, and his reforms shaped the character of the Empire for the next 300 years. Diocletian paved the way for his great successor, the Emporer Constantine who founded Constantinople and established Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire.

The most important third-century emperors

Septimius Severus 193–211

Caracalla 211–217

Claudius Gothicus 268–270

Aurelian 270–275

Probus 275–282

Diocletian 284–305