Roman art: 117 to 550

Hadrian's villa (c. AD 130), the most extravagant of all Roman country palaces, represents the eclectic tastes and restless architectural experimentation of a Roman ruler with unlimited resources. No single building is on a grand scale but the whole – an immense variety of courtyards, fountains, statues, pillars, pools, mosaics and individual buildings – covers 18 square kilometers (7 square miles) of countryside on the edge of the Roman Campagna and is skillfully blended into the landscape.

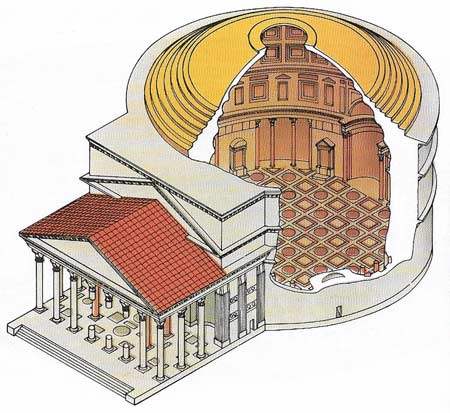

The Pantheon, Rome (c. AD 118–c. 125) is one of the most influential buildings in the history of architecture and has been described as the first major monument to be composed entirely as an interior. Rebuilt completely by Hadrian it remained the world's largest domed structure until modern times and is the oldest building with its original roof intact. The portico, supported by 16 granite columns, is grandiose but conventional. But the dome, a perfect hemisphere, is remarkable not only for its size – 43.2 meters (142 feet) in diameter – but for its apparent lightness, an illusion skillfully created by the use of coffering, once stuccoed and gilded, and a single central light source. The actual method of construction is still not fully understood but involved a highly sophisticated and deep grasp of concrete technology.

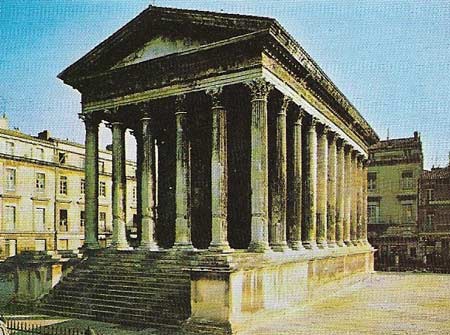

In the Corinthian-style Maison Carrée, Nîmes, Hellenistic architecture is modified to accommodate the special requirements of the Roman religion, which placed emphasis on the interior rather than the exterior of a temple. The top two of a flight of steps form a threshold below the cella (the enclosed portion), the width of which equals the length of the portico. The colonnade is continued round the outside of the cella but, unlike that on a Greek temple, is embedded in solid walls. Modelled on prototypes in Rome it is one of the best examples of Roman temple architecture of the Augustan age.

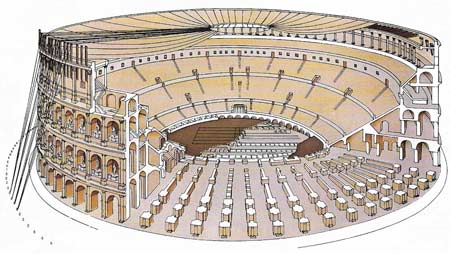

The Flavian amphitheater in Rome – the Colosseum – was conceived by the Emperor Vespasian and constructed between AD 72 and 81. It was one of the greatest Roman architectural achievements and served as a model for amphitheaters throughout the empire. Its outer framework and basic interior structure were composed of gigantic blocks of travertine (a kind of hear limestone), the remainder being built of softer stone and concrete, largely faced with marble. Rising 45.7 meters (150 feet) in four stories the arcaded facade included columns of all three orders – Doric, Ionic and Corinthian – with the upper part decorated with numerous statues. As many as 45,000 spectators, who gained admittance through 80 entrances, sat on tiers of marble seats arranged by class. They were protected from sun and rain by a movable awning.

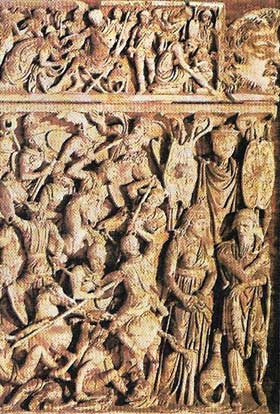

The Arch of Constantine is decorated with a rich variety of panel reliefs and statues, many of which were plundered from earlier public monuments. It thus summarizes the major artistic styles from Trajan to Constantine. It indicates a change towards painting and mosaics.

This great dish, part of the Roman silver hoard known as the Mildenhall Treasure (4th century AD), measures almost 60 cm (2 ft) across and weighs 8.3 kilogams (18.3 pounds). The outer frieze represents the triumph of Bacchus, god of wine, over Hercules. Other mythological figures, including Neptune, also appear.

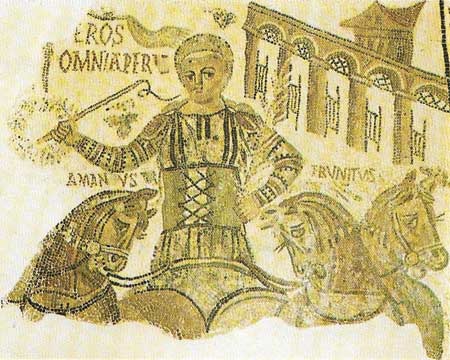

The technique of mosaic, invented by the Greeks, was readily adopted by the Romans who perfected it and applied it on a large scale. Many local styles emerged in Italy and such provinces as Britain and Tunisia. Among the subjects employed are stories from classical mythology, interpretations of classical Greek paintings, landscapes, portraits, elaborate decorative motifs and particularly scenes of vigorous action – chariot racing, hunting and gladiatorial spectacles. By the 3rd century mosaic work had, in many instances, superseded the three-dimensional representations of gods and cult figures, as in mosaic portraits.

In the time of Trajan there was a revival of interest in the art of earlier periods which reached its apogee under his successor Hadrian (AD 76–138). The unprecedented economic prosperity of the empire, coupled with the emperor's personal patronage, led to a veritable Hellenic renaissance that persisted through Hadrian's reign and beyond, determining to a large degree the character of Roman art in the 2nd century AD.

Hadrian's architectural revival

Hadrian's villa at Tivoli, described as "probably the most beautiful collection of ruins on Italian soil", was the most remarkable of all Roman architectural complexes. He made lavish use of multi-colored marble and of diverse ornamental architectural features including the curved architraves that were popular in the Eastern Empire.

These and the innumerable Greek and Greek-influenced masterpieces of sculpture wit which Hadrian surrounded himself introduced many new and important elements into the Roman artistic repertory. He created such emphatically Roman works as the Pantheon – the most important domed structure of the age. Under the Antonine emperors who succeeded Trajan, architecture was predominantly Greek in inspiration. Much use was made of the three orders and many massive works, such as large temple complexes, were built, especially in the Eastern Empire. A number of new architectural devices were employed, including ostentatious facades, exotically decorated (but detached and functionless) columns which visually fragmented interiors, niches in which works of sculpture were placed, and a profusion of surface decoration of all kinds.

During the rule of the Severan emperors in the third century, the rise of status and wealth of citizens in the Roman provinces in particular was asserted in a range of lavish architectural works. In an attempt to vie with the achievements of earlier emperors, such rulers as Caracalla (188–217) embarked on a number of grandiose building schemes that produced a wide range of structures. These were most notable for their impressive size and the pretentiousness of their decoration.

Among them one may include the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, the best preserved of all imperial baths. It accommodated 1,600 bathers and its central hall (tepidarium) was roofed by a vault soaring to a height of 54.8 meters (180 feet), decorated with colored marble and the most priceless statues. But in keeping with the Roman preference for interior rather than exterior elaborateness, it was largely undecorated on the outside.

The reigns of the later emperors of the third century and their preoccupation with the defence of the empire did not encourage major building programmes, other than those to do with military works. The fortified palace of Diocletian (245–313) at Spalato (Split) in Dalmatia (completed 305) stands out as the major military building of the late period and symbolizes the swing from decoration to pure functionalism.

Sculptures to the 3rd century AD

Through Hadrian's influence, the earnest majesty of the sculpture from Trajan's era was replaced by Greek works in which sensual beauty predominates. From c. AD 100, for reasons that are not fully understood, burial began to replace cremation as the customary method of disposing of the dead throughout the Roman Empire. From this time tombs became more elaborate and the art of making decorated sarcophagi – such as the Portonaccio Sarcophagus – of military leaders.

|

| The Portonaccio Battle Sarcophagus depicts Romans on a frantic struggle with barbarians and captures the moment when victory is unquestionably the Roman commander's. The Emperor Hostilian (d. 251), detached from the mass of bodies, completely dominates the scene. The craftsmanship represents a theatrical example of mid-3rd century art.

|

In the Antonine period statues became more massive and elaborate. The use of chisels for carving stone was steadily superseded by the skilful use of the drill which enabled the production of more decorative effects in drapery and hair. Fine bronzes, such as the powerful equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius (121–80), were produced but few have survived.

|

| This bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome dates from the Antonine period when idealized figures began to displace the realism found under Trajan. Once gilded and with a figure of a barbarian under the horse's raised hoof, it was preserved while other Roman bronzes perished in the mistaken belief that it depicted the Christian Emperor, Constantine. The statue influenced the work of such renaissance masters as Donatello (c. 1386–1466).

|

Two particular types of relief coexisted from this period – a primitive, almost folk-art style, as shown on the column of Marcus Aurelius and the persistence of Greek classical elements – two streams of artistic endeavour that came together in the Arch of Constantine.

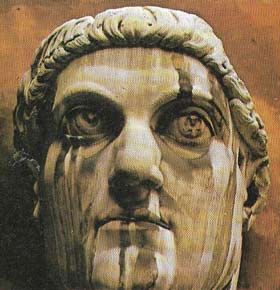

Under the Severan emperors massive statues and reliefs were often so elaborate that they virtually obscured entire architectural surfaces. Sculpture of the turbulent third century was of variable quality – reliefs became cruder and there was a trend toward mannerism and abstract symmetry, which involved reintroduction of the chisel in place of the drill. This resulted in the angularity found in such stark and impressive works as the colossal head of Constantine.

|

| This head from the colossal statue of the Emperor Constantine in Rome is the largest statue of the age – ten times life size. It was sculpted in c. AD 313 and was the peak of imperial art.

|

Painting and crafts

Painting did not apparently develop beyond the so-called Fourth Style identified at Pompeii. Mosaic, originally a flooring technique, developed rapidly in the second and third centuries and virtually replaced painting as a method of decorating walls.

Despite several imperial decrees against personal extravagance, fine jewelry, splendid ivory-inlaid furniture and a wide range of metalwork, such as the silverware found at Mildenhall, England, were popular throughout the empire.

|

| In this gold medallion minted at Thessalonica, the Emperor Constantine appears in a portrait that echoes those of Augustus. The restoration of order to the Roman Empire under Diocletian and Constantine prompted the standardization of Roman coinage. While achieving a high degree of craftsmanship, representations of rulers became stylized with religious overtones – a typical aspect of late Roman art, foreshadowing that of Byzantium.

|