rural life in medieval England

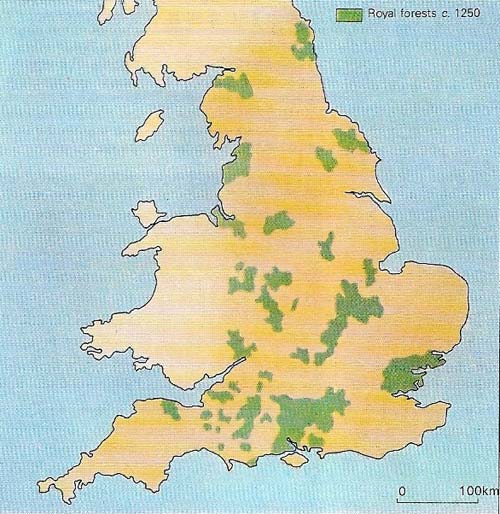

Figure 1. Royal forests took up a significant proportion of the land of England in the 13th century. Woodland was as important to the medieval economy as open country for it yielded not only timber and charcoal, but served as a reserve for game and provided pasturage for pigs. After the Norman Conquest the Crown began to assert its authority to gain control of the woodland, designating areas (and sometimes whole countries) as royal forests in which rights of hunting, farming and gathering were severely restricted. These controls were often resented by local inhabitants, and disputes over encroachments by farmers seeking to extend their estates were common throughout the Middle Ages.

Figure 2. The reeve was the local agent of the landowner, and he was often a native of the village in which he officiated. Despite this he was frequently depicted as a tyrant. Here a reeve is shown directing peasants as they reap on the lord's demesne.

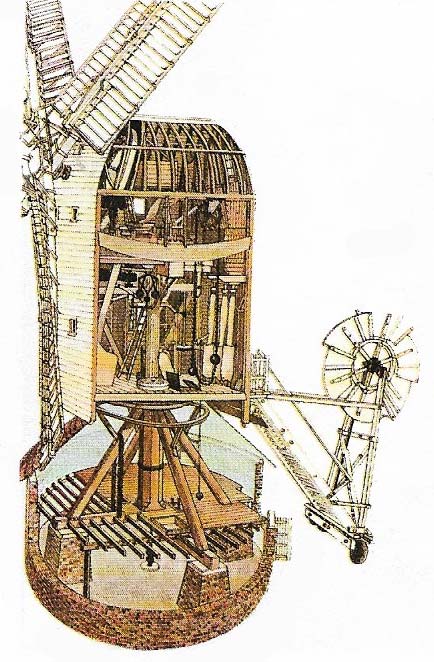

Figure 3. The postmill, an elaborate version of the windmill, was introduced into England in the 1180s and quickly became common. The whole mill turned to face the wind. A monopoly of milling was an important part of a feudal lord's authority in his manor.

Figure 4. The birth-rate in the 13th century was higher than today, but infant mortality varied between 15% and 20%. Once a man reached the age of 20, he might expect to live to 50. The Black Death, however, severely reduced life expectancy, even in the countryside.

Figure 5. Peasant farming generally took place in open fields. Signs of these fields can still be seen in some places, as here in Crimscote, Warwickshire, where the patterns of medieval furrows, undivided by hedges or fences, can be detected by aerial photography. Fields were divided into strips, which were measured by the amount that could be ploughed in a day. They were distributed by lot, annually at Michaelmas, so that a man's fields changed each year. A primitive system of crop rotation, with one field out of two or three laying fallow while wheat alternated with oats or barley, was usually operated; but without adequate manure, the yield was only half that of modern agriculture.

Figure 6. Stokesay Castle, Shropshire, was built between 1260 and 1300 and was a fortified Manor House in the characteristically expansive and lavish style of the age of "high farming" and booming agricultural rents. It's wide halls without aisles, and its tall traceries windows, seem to represent a new standard of comfort for the provincial landowner. The solar wing with small chambers indicates a growling inclination for privacy. But the polygonal tower and gatehouse serve as reminders that Stokesay was in the unruly Marches, or border areas with Wales; the whole enclosure could provide protection for the village from raiders.

Figure 7. The center of wealth in medieval England shifted dramatically after the mid-14th century from the champion, or open, country of the Midlands, that concentrated on crops, to the sheep-runs and cloth-production areas of southwestern and southeastern England with their flourishing entrepôts of Bristol and London. The map shows the percentage increase in wealth of each country over the period 1334–1515. Village cloth-making, which depended on the fulling-mill that needed clear, fast flowing streams, probably accounts for the growing prosperity of Somerset and the Cotswolds. The wealth of Kent and Essex was more broadly based, as the wealth of London reached the home countries. The north stayed relatively backward.

Figure 8. Lavenham, Suffolk, was one of a series of East Anglian towns that won great prosperity in the 15th century, arising from the production of wool and a certain amount of cloth. As well as boasting an extravagant "wool-church" financed by this industry, Lavenham's wealth was seen in the elaborate timber-framed houses, which have been preserved almost intact. In such houses the art of domestic living was perfected, unassailed by the pressures of town life that prevailed in more urbanised boroughs. The old central hall was divided into several units, including a solar or small hall, and probably a kitchen. The fireplace was an original part of such houses, and was situated on a wall instead of in the center of the hall. Glazed windows were another luxury.

Figure 9. Wool provided one of the most important sources of English wealth in the Middle Ages. The Flemish and, later, the English cloth industries were almost insatiable, and after the 12th century when the numbers of sheep overtook pigs. Sheep farming brought great profits to many areas. In the late Middle Ages, peasant-owned flocks became as important as those belonging to the lords, as peasants' estates grew in size.

The structure of the English village originated in a deliberately chosen pattern of settlement. Brought to England probably by the Anglo-Saxons, it was characteristic of the open landscape of northern Europe. Except in the west and north, where Anglo-Saxon settlement was less complete, it generally replaced the isolated farmsteads of the Celts, and was well suited to the cultivation of the open or "champion" country of the Midlands and southern England.

The medieval English village

In the 11th century villages acquired the characteristic shape and size that survives today, clustered around a church and often a green. Little essential has changed since Domesday Book (1086), in which were recorded almost all the settlements and village structures that now exist: the large village greens typical of north Yorkshire and many other areas, the straggling villages of much of East Anglia, the hamlets of Dorset. By 1100 the idea of several families living in close proximity and cooperating in the agricultural tasks had wholly taken root.

The peasant's house usually stood in its own vegetable plot. Many peasants also owned a pig or a few fowls. The whole family took part in the struggle for survival: the women looked after the garden and made the normal leather clothes (and, after 1350, the woollen clothes that slowly replaced them) while the men worked in the fields. The primitive implements included the ox-drawn plow, but backbreaking work from sunrise to sunset was still necessary both in the peasants' own fields and in those of the lord to whom they owed labor services. A monotonous diet of bread and ale (not yet flavoured with hops) was only partly mitigated by vegetables and fruit, although the plentiful livestock of most parts of England made meat-eating reasonably frequent for all classes.

|

| Most of the tasks of the agricultural year were done by hand. The agricultural writer, Walter of Henley (fl. 1260) advised that seed should always be brought from other manors at Michaelmas, because it grew better than the home-produced product; and similar lore surrounded other jobs. Agricultural output was at its medieval peak in the 13th century when many improvements to estates were introduced and virgin land was cultivated. |

The social system of the village

In any village there were men of many different social degrees. In the eleventh century there were geneats (a lord's free retainers and messengers), cottars (who in theory owned five acres but owed labor services to the lord), and geburs (who had more onerous services than cottars); landless laborers and slaves also existed in some areas. By 1200 these various distinctions had been simplified into freemen, who could sell their land and leave the village, and villeins (bond-men), who were hereditarily tied to their lord. These classes, however, were not exclusive or separate. The extensive records of Ely show that free peasants, villeins, and laborers intermarried, and by the early 14th century some villeins could buy and sell property without hindrance and amass considerable personal wealth. Whatever the importance to landowners of the legal status of peasantry, it was certainly less central to peasant society itself than the ties of kinship and membership of the village community.

The village community demanded organization, and most villages of the thirteenth century were "manors", or estates owned by a lord (whether resident or not) and composed partly of demesne (fields directly cultivated for him) and partly of fields held by peasants in return for rent or week-work (Figure 5). Labor services varied widely, but they generally included up to six days' plowing or reaping (Figure 2) for a few weeks of every year (perhaps two days at other times) and additional "boon-work" at harvest time, as well as carting, tending the lord's garden, and marling (fertilizing).

|

| Hunting was an overriding passion for King John (r. 1199–1216), as well as many other kings. William II (r. 1087–1100) died in a hunting accident and the itineraries of many rulers' journeys through the realm were tours of their hunting lodges, some of which, such as Woodstock in Oxfordshire, developed into sizeable towns. Forests were richly stocked with bear, wolves, boar, and all kinds of deer. Falconry was also practiced. |

Declining feudal obligations

These obligations were often taken lightly; in theory milling at the manorial mill (Figure 3) or baking in the manorial oven, for a small payment, were heavy duties upon unfree peasants, but in practice the absence of many landlords could render them obsolete. In some instances, as at Wigston Magna, Leicester, the village was divided between two manors, and the peasants plowed together the common fields of both manors; feudal obligations there can have amounted to little more than a few customary dues. From the twelfth century, labor services were increasingly commuted to money rents. The manorial lord controlled justice amongst his villeins, but villagers could apply to hundred or shire courts, in which they might hope for a greater degree of impartiality in cases involving their lords.

By the fourteenth century the life of the peasant was changing rapidly. The pressure of population before 1300 (Fig 4) led to great distress, exacerbated by the great famine of 1315–1317; but the Black Death of 1348–1350 and its recurrences in the next half-century dramatically reduced the number of mouths to feed. It brought about a shortage of labor and so forced up wages, despite attempts to hold them down. While prices remained stable, the wage for a farm laborer doubled between 1350 and 1415. At the same time the great estates were less often directly farmed, and instead the demesne was rented out. Thus the distinction between free and unfree came to be irrelevant in practice, and the yeoman farmer, with consolidated fields and wage-earning farm laborers, began to dominate the rural scene. Numerous solid and prosperous 15th-century yeoman farmhouses, separate from the village, are a feature of much of the English countryside, a symbol of the decline of the manorial system.