Trojan War

Figure 1. Panoramic view of the siege of Troy. On the left is the coast of the Aegean Sea, and the Greeks' ships and tents; on the right, the powerful walls of the besieged city, with sentries on guard; in the center, the Trojan plain where much of the fighting took place.

Figure 2. The Greek ships sail across the Aegean Sea to land the expedition on the coast of Asia Minor, before starting the siege of Troy.

Figure 3. Achilles, outside the walls of Troy, about to kill Hector with his spear.

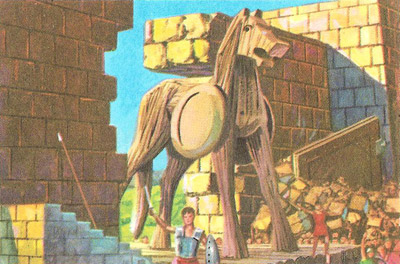

Figure 4. The Trojans bring the wooden horse inside the walls.

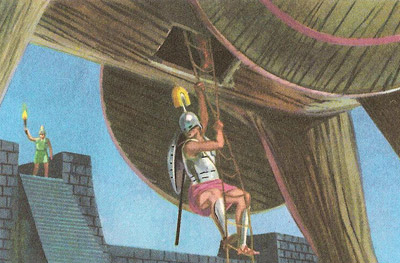

Figure 5. The Greek warriors climb down from the horse and open the city gates.

If you had asked a Greek of the time of Socrates: 'What are the greatest wars of history?' he would have certainly have mentioned the Trojan War.

Troy was a very strong city in the north-west corner of Asia Minor, not far from the Dardanelles. The great was between Greeks and Trojans towards the end of the Bronze Age caught the imagination of the Greeks, and many stories were told about it.

Homer

|

| Marble bust of Homer, the Greek epic poet. He was

said to have been blind, and to have told his stories in the accompaniment

of his lyre.

|

The greatest of these stories are wonderfully narrated in two long epic poems, the Iliad, which means 'poem about Ilium' (another name for Troy), and the Odyssey.

The Iliad does not tell the whole story of the siege and capture of Troy, but it describes a few important incidents during the siege. These include the quarrel between Agamemnon, the Greek leader, and Achilles, the greatest of the Greek warriors; and also the fight to the death between Achilles and the Trojan champion Hector. The Odyssey relates the adventures of Odysseus,another of the Greeks, on his voyage home to Ithaca when the Trojan War was over.

According to tradition, both the Iliad and the Odyssey (and some other epic poems about the Trojan War as well) were composed by Homer. But even the ancient Greeks themselves knew nothing at all for certain about Homer – who he was, and where or when he lived. Many legends (for instance, that he was blind) grew around him, and no fewer than seven different cities claimed the honor of being his birthplace. Many scholars today believe that both the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed orally (without the aid of writing), and that they were told and retold many times, constantly being improved and expanded, over a period of many generations. 'Homer' might well have been the greatest of a long line of epic poets. But whatever their views on the 'Homeric Question', all scholars agree that the Iliad and Odyssey are among the finest literature of all times.

The beginning of the war

Greek legends give the following account of how the War began.

Priam, the aged king of Troy, had a son called Paris. This young prince went to Sparta as a guest of Menelaus, king of that city. While there, he fell in love with Menelaus' beautiful wife Helen. Secretly, one day, he carried her off on his ship, and took her back with him to Troy.

Not surprisingly, Menelaus was very angry at this flagrant breach of hospitality; besides, he wanted his wife back. So he called the other Greek kings to his aid.

The Greek expedition

The kings and princes of Greece rushed to help Menelaus. Each brought with him a contingent of ships and soldiers; each was himself a mighty warrior. The most famous among them were 'swift-footed' Achilles; Agamemnon, 'king of men'; 'resourceful' Odysseus; Diomedes, 'good at the war-cry'; Aias (or Ajax); and Nestor, the king of the Pylos. Menelaus' brother, Agamemnon, commanded the expedition.

A ten-year siege

So the Greek fleet sailed across the Aegean, and landed on the coast opposite Troy (Figure 2). The siege of Troy began: few could have realized it would last so long (Figure 1). The city was surrounded by high walls which could not be taken by assault. Furthermore, the Trojans and their allies kept on making dangerous sorties. Most notable among the Trojan warriors were Priam's son, Hector, 'with the glittering helmet', Paris, Sarpedon, and Aeneas.

The battles continued in the plain between the city and the sea. According to the Iliad, the gods of Olympus followed the course of the war with great interest, and sometimes even went down on to the field of battle to help one side or the other. Hera (wife of Zeus), Athene, and Poseidon (god of the sea and of the earthquake) were on the Greek side; Ares (god of war), Aphrodites (goddess of love), and Apollo all helped the Trojans.

The wrath of Achilles and the death of Hector

In the tenth year of the war there was a severe quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon. As a result, Achilles and his men withdrew from the battle. In his absence the Trojans were able to force the Greeks right back to their camp and their ships, and even to set fire to one of them.

Achilles was persuaded to allow Patroclus, his closest friend, to go out and fight the Trojans wearing Achilles' armor. At first Patroclus was brilliantly successful; but eventually he was killed by Hector, aided by the god Apollo. After fierce fighting the Greeks managed to recover Patroclus' body but not before Hector had stripped it of Achilles' armor.

Roused by the death of his friend, Achilles at last ended his quarrel with Agamemnon and agreed to fight again. Hephaestus, god of the smithy, was persuaded to make him new weapons. With these he went to fight great Hector and avenge Patroclus.

Hector could not at first face Achilles, who chased him three times around the walls of Troy. Then Achilles threw his spear, but missed; Hector hit his enemy's shield with his own spear, but did not pierce it. Then he drew his sword; but Achilles struck him in the throat with the spear the goddess Athene had brought back to him (Fig 3).

Achilles then dragged Hector's dead body in the dust behind his chariot back to Greek camp. But next day the aged king Priam came there in person, and begged Achilles to give him back the body of his son. Achilles took pity on him and consented.

The death of Achilles, and the Trojan horse

Thus, in the tenth year of the war, Troy lost its bravest defender. But this didn't mean victory for the Greeks: a short time afterwards Paris killed Achilles with a poisoned arrow in his heel – the one vulnerable part of his body.

At last the 'resourceful' Odysseus thought of a way to end the war. The Greeks pretended to abandon the siege and sail away home. On the beach they left an enormous wooden horse – in which were hidden Odysseus and his companions. The Trojans were utterly deceived: they pulled the horse in triumph inside the city. But that night the horse opened; the Greeks inside opened the gates to their friends outside, and the city was taken (Figures 4 and 5).

A terrible massacre followed. Almost all the men were killed; the women were captured and carried off to Greece as slaves. The aged king Priam was also killed; Troy was burnt and utterly destroyed. The war was over, and Menelaus at last regained his wife.

Told in Greek literature

Not all the episodes related above are in the Iliad. Some are told in the Odyssey; some other works of Greek literature; and some in another epic poem (modeled on the Iliad and Odyssey) called the Aeneid, written by the Roman poet Virgil. Virgil tells how Aeneas escaped from the destruction of Troy, and how he eventually settled in Italy. He was the forefather of Romulus, legendary founder of Rome. All this is a wonderful story, but how far is it true?

There really was a city of Troy. It was discovered by the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. Of the nine successive Troys, Troy Vlla could withstand a long siege, but it was thoroughly and deliberately destroyed by enemy hands, and then systematically burnt. And the date? Somewhere around 1240 BC – the very time in which Greek tradition placed the Trojan War. Hittite inscriptions of the period make it very likely that Greeks and Trojans fought then (although perhaps not about Helen).

Excavations of the Bronze Age in Greece, and the decipherment of the Linear B tablets show that the political situation in Greece at that time is accurately described in the Iliad. Other studies of conventional epithets in the Iliad even make it seem likely that some of the names are historical, notably Agamemnon, Achilles, and Hector; but others, such as Aias, and perhaps Odysseus, probably belong to an earlier age.