the Tudors and the new nation state

Figure 1. Henry VII and his queen with their children are depicted with St George and the dragon on this altarpiece, probably made for the royal palace at Sheen. The prominence given to the green in early Tudor art was new. This painting commemorated Henry’s patronage of the Order of the Garter, which honoured equally the old nobility and new soldiers of fortune. Henry did not intend to crush the nobility into submission but rather to forge a new alliance with them. But his unpopular taxation seemed to show that Henry had autocratic intentions. His ministers Richard Empson (d. 1510) And Edmund Dudley (1462-1510) were condemned for treason after the king’s death.

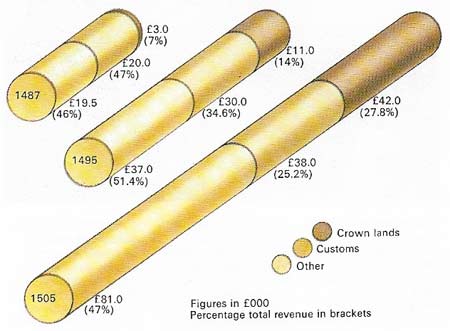

Figure 2. Henry VII's revenue grew dramatically in his reign, based on an extremely careful management of Crown estates. Henry aimed to "live of his own" and tried to make even war profitable, by keeping costs low and suing for peace, thus staying independent of both nobility and Parliament. In this way he hoped to establish a strong monarchy, which he regarded as a vital prerequisite of English political authority in Western Europe.

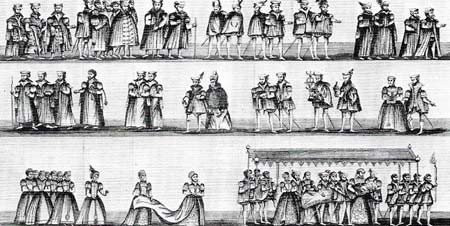

Figure 3. The baptism of Arthur (1486–1502) Henry's eldest son, was an occasion for a typical royal procession. The name Arthur's was chosen to echo that of the semi-mythical British hero whose cult was at its height in the 15th century and to stress the Welsh origins of the Tudors. Similar events were organized at the start of his reign for each main town, to affirm the glory of his rule. Henry also planned a major addition to Westminster Abby, begun in 1509.

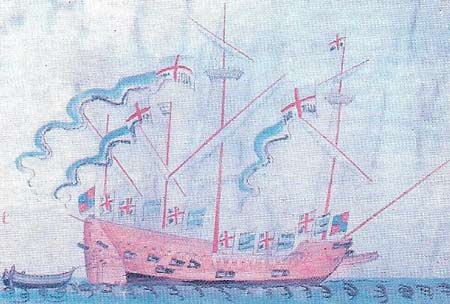

Figure 4. The Henry Grace a Dieu, a carrack of 1,000 ton was built in 1510–1514 and became Henry VIII's flagship. By 1510 Henry had won a strong position, holding the balance of powers between the Hapsburgs and Valois, but he was never able effectively to assert his authority in Europe although he defeated the French in 1513.

Figure 5. Thomas Wolsey, who had ambitions to become pope and to dominate European politics, was the chief architect of Henry VIII's foreign policy before 1529. As papal legate he had great power on the English Church, and seemed almost independent of the king's jurisdiction.

Figure 6. Thomas Cromwell was the architect of the English Reformation. His ruthless determination, born of soldiering on the Italian wars and in business experience in The Netherlands, served him in good stead in Wolsey's service and later in the king's. A genuine supporter of reform he believed that the king should be the head of the English Church. He excelled as parliamentary manager, marshalling the broad support that the Tudor monarchy enjoyed, to create a great series of Acts establishing the royal supremacy and suppressing the monasteries. His extraordinary executive ability helped him to enforce them through his system of informers and active control of the JPs. He made many enemies, particularly amongst the nobility, and in 1540 he was executed for treason.

Figure 7. Henry VIII was an imperious man whose will dominated the political history of his reign, his court was a focus for all kinds of artistic patronage and with John Skelton (1460–1529), the poet, as his tutor he was probably the first English king to know Italian and Spanish. He took advantage of the shrewd diplomacy of his father to make England a respected state, fighting many costly, although rarely glorious, wars. In this policy he claimed to embody the new assertiveness and aggression of Englishmen overseas that also found expression in the steady erosion of the Hanseatic League's monopoly of English trade. The culmination of this nationalism was the Church's break with Rome.

When Henry Tudor (1457–1509) (Fig 1) took the English Crown from the last Plantagenet king on 22 August 1485, he became master of a rich kingdom. Its fertility and its mineral wealth appeared to a Venetian observer of 1500 to be "greater than those of any other country of Europe"; its trade in the northern and western seas was increasing rapidly, and its population was slowly growing. Yet the monarchy itself had minimal prestige, ruined by the mental incapacity of Henry VI (reigned 1422–1461; 1470–1471) and the confusion of the Wars of the Roses.

|

| The striking of medals was a characteristic form of propaganda in the 15th and 16th centuries. Henry VII used them together with other projections of the royal image in pageantry and artifice to bolster his weak hereditary claims to the throne. His marriage with Elizabeth of York (1465–1503), shown here with Henry, was thought to give him a much better title to the throne than the right of conquest or the Act of Parliament upholding it, both of which could be reversed. His use of the "Tudor Rose", combining both the red and white roses, symbols of the two factions in the War of the Roses, exemplified his desire to appear as unifier of the nation. |

The establishment of the Tudor dynasty

In 1485 few estimated that Henry VII's new dynasty would last long; Henry had to earn respect. There were potentially dangerous challengers to his throne: Simnel Lambert (c. 1475–1525), who pretended to be the imprisoned Earl of Warwick (the last male Plantagenet) and who momentarily won over Ireland; and Perkin Warbeck (c. 1474–1499) whose claim to be Richard of York, the younger of the princes murdered in the Tower, was taken up by many European rulers. Henry survived partly because of his prudent statecraft, but primarily through the desire of all classes for firm leadership and an end to political uncertainty.

Henry is said to have introduced a "new monarchy", but actually it was no more than the new life breathed into traditional institutions by a strong personality. Although parsimonious, he understood the value of ceremony (Figure 1) and pageantry (Fig 3) and his court impressed foreigners. Behind this façade lay the increasingly solid support of most of his subjects. The old nobility, weakened but not extinguished by the civil wars, was happier with a subordinate role than before. Henry treated most of these families with respect: he passed the Statute of Livery and Maintenance in 1487 against keeping private armies, but it did not seriously affect their retinues or their local influence.

The king rested his power upon the traditional rulers of the counties, the gentry as justices of the peace; he gave them stronger authority than before and framed his policies with a careful eye on what they would accept. In particular, he emulated Edward IV (reigned 1641–1470; 1471–1483) in a policy of peace and therefore low expenditure: he avoided straining the loyalty of the gentry with extensive taxation (Fig 2). The main achievement of Henry VII was to nurse the monarchy back to its traditional role of leadership by avoiding serious confrontation with any group of subjects.

The court of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (reigned 1509–1547) (Figure 7) was the' first Prince of Wales to succeed peacefully since 1422. Far more obviously than his father, the second Tudor king was a typical Renaissance prince: well educated, polyglot, author of a sprightly theological work against Luther, accomplished on lute and harp, a jouster, and a bowman, combining magnificence with intellectual power and political will exactly as the age demanded of its rulers. His court was a centre for the new learning: his ministers Richard Fox (c. 1448–1528) and Thomas Wolsey (c. 1475–1530) (Figure 5) were great patrons, and his later chancellor, Thomas More (c. 1478–1535), embodied more than any contemporary Englishman the cultivated practical intellect of the Renaissance. Henry's cruelty in the interest of state, dramatically evidenced in the fate of four of his six wives (two of whom were executed and two divorced), only underlines the brilliant. thunderous atmosphere of his court.

Whether wittingly or not, Henry's use of the revived authority of the Crown had, in the form of the Reformation, revolutionary effects on England. He was initially content to work through powerful ministers, the first of whom, Thomas Wolsey, cut a figure as a cardinal hardly less magnificent than his master's. Wolsey established a position of unprecedented dominance in Church and State. Even before the Reformation he planned a wide-ranging reform of the Church, but it was unachieved at his fall from power in 1529, and his legacy was a hierarchy henceforth subservient to the king alone.

>

|

| Walmer Castle, Kent, was one of the fortresses built by Henry VIII in 1539 as part of a system of coastal defence during a brief alliance of his enemies the Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France. These castles used the most modern style of fortification. |

Cromwell and the bureaucracy

By 1534 Henry had found in Wolsey's former servant Thomas Cromwell (r. 1485–1540) (Figure 6) a minister to carry through all the implications if the break with Rome. and realize the new potential power of the monarchy. A hard, practical man, Cromwell used the growing authority of Parliament. In his popular reformation of the Church, he was supported by the gentry, whom he manipulated with his system of patronage and an unprecedented network of informers. Yet even Cromwell was only an instrument of government, dismissed and executed by the king in 1540 when his enemies won the ear of Henry.

>

|

| The Pilgrimage of Grace was a rebellion of the north in 1536 in opposition to the Oath of Supremacy demanded of all ecclesiastics in 1534. This picture of 1539 shows the judge leaving the execution of Thomas Marshall, abbot of Colchester, who verbally supported the rebellion, uttered treasonable ideas in private and who was determined to resist the suppression of his monastery. It was typical of Cromwell's rule that men could be executed for opinions expressed in private. |

Henry VIII was by then the master of a terrifying royal power, sustained by an efficient and much reformed bureaucratic machine, and able to impose his own middle way between the proponents of a radical reformation and the adherents of the old, Catholic ways. His achievement, a remarkable display of statecraft, was to have under-stood and given a lead to the strongest strands in public opinion, from which, as institutionalized in Parliament, he never moved very far. By the time of his death in 1547, the Tudor monarchs had become the natural expression of the growing national confidence of sixteenth-century England.