urban consequences of industrialization

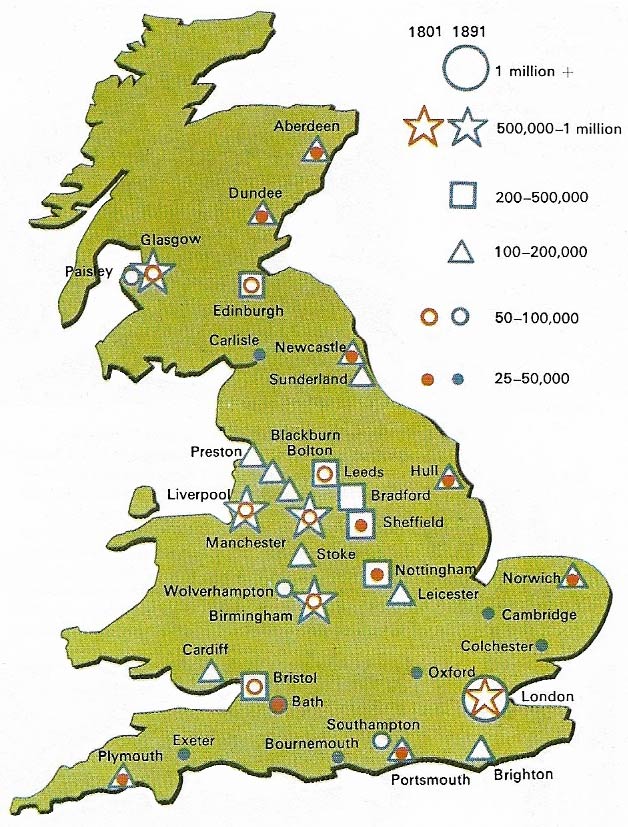

Figure 1. In 1700 only an estimated 16 percent of the population in Britain lived in towns of more than 5,000 people. The Industrial Revolution and its attendant dramatic population growth in the 18th century created a predominantly urban society by 1900, when 77 percent of the population lived in towns. This growth of the new towns and cities within 200 years bore little relation to the pattern of towns in pre-industrial Britain. Instead the expansion was almost entirely dictated by economic necessity. Some of the most spectacular growth took place in parts of the country that had been least densely populated in the pre-industrial era, such as Lancashire, Yorkshire, northeast England, South Wales and the Lowlands of Scotland. These industrial regions dominated the UK economy until the economic slump of the Depression in the 1920s and 1930s.

Figure 2. The human conditions behind the creation of the first industrial nation were tragic. The unprecedented changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution on Britain's demographic character brought an equally dramatic decline in the social conditions for the majority of the population. Glasgow, an expanding city of more than 100,000 people, had only 40 sewers in 1815. This horrific level of sanitation and hygiene caused an increase in the death rate, and the city's population level would actually have declined in the 1820s and 1830s had it not been supplemented by steady immigration.

Figure 3. Cramped back-to-back housing was constructed to accommodate the expanding populations of the early industrial towns. The growth of some old towns was actually restricted by local landowners who feared that their power would be undermined by the new industrial masses. This led to chronic over-crowding within the boundaries of the old towns. Only in the mid-19th century did the government begin to introduce legislation to clear and improve unsanitary areas.

Figure 4. Middlesbrough was literally a creation of the Industrial Revolution. In 1801 it was a tiny group of houses of only 25 inhabitants; but by 1901 the population was more than 90,000, with iron, and later steel, as the principal industry. Without the railways, in this case the Stockton and Darlington line, the town would probably never have existed. The carefully planned growth of the streets and houses, still evident today in this aerial view, was the product of its Quaker founders, who first recognized its great commercial potential at the terminus of the new railway line. In the space of 100 years, Middlesbrough had become one of the commercial prodigies of the 19th century.

Figure 5. Railways not only led to the spread of towns into the countryside, the creation of "suburbia", but they also resulted in the creation of holiday resorts for the industrial workforce. Blackpool and Scarborough are examples of seaside resorts that developed in the 19th century a short train ride away from industrial regions. Here holidaymakers are shown leaving London for Cornwall in August 1924.

Figure 6. London's Barbican housing project is a fine example of redevelopment that took place after the blitz destroyed large areas in many of Britain's cities. Historic features such as St Gile's Church were sensitively incorporated into the scheme; and pedestrians and traffic were separated. The complex includes shops, a theatre, restaurants, and a concert hall.

Pre-industrial Britain was a predominantly rural society in which there was only one large city, London, and a few other large towns. In 1700 London had a population of more than half a million, but only six towns had populations of more than 10,000. Many parts of the country supported only villages and small market towns with populations of fewer than 5,000. Population growth from the mid-eighteenth century combined with the expansion of industry transformed Britain into a predominantly urban nation.

The growth of towns

By the middle of the 19th century, there were more than 70 towns in Britain with populations of more than 10,000, eight with more than 100,000 and Glasgow, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool had more than 250,000 inhabitants. By 1851 more than half the population lived in urban areas, compared with about a sixth in 1700 (Figure 1). This growth continued until the eve of World War II, when more than four-fifths of the total population of Britain lived in urban areas. Only in the mid-twentieth century has the spread of urbanization in Britain been reversed. Continued suburban development and the growth of car ownership have permitted more people to live outside urban areas in the years since 1945 (Figure 5).

|

| Industrialization has created a more affluent society. Previously the predominantly agricultural population had been almost entirely dependent upon fluctuations in harvest levels. Until 1850 it is true to say that the overall standard of living did not decline, although it was subject to severe fluctuations and regional discrepancies. After that time, the standard of living of the population rose, with higher real wages, and kept to a more consistent level. This is shown in the provision of public amenities such as schools, roads and hospitals as well as in the level of personal consumption. |

One major impact of population growth and industrialization was rapid urbanization. Population in Britain rose three-fold between the middle of the eighteenth century and the middle of the 19th, from more than 7.5 million to more than 21 million. Although population growth occurred in the countryside as well as in the towns, urban centres expanded both from internal increase and migration from rural areas. London received between eight and twelve thousand immigrants a year by the end of the eighteenth century. In addition, the redistribution of population was changed – new industrial regions such as Clydeside and Lancashire became principal centres of growth.

New industries often recruited substantial portions of their labour force from the surrounding countryside. Short-distance migration, of not much more than 30 or 40 kilometers (20 or 30 miles) in most cases, was the general rule within Britain. Some immigrants, however did come from further afield – from Scotland, Ireland, and rural Wales.

Local government created

The rapidity of growth is well illustrated by Manchester. A population of 75,000 in 1801 had grown to nearly 750,000 inhabitants by the eve of World War I. These tremendous increases in urban population almost completely swamped the provision of social amenities and local government. Until 1835, Manchester was still governed as though it Were a rural parish, although it had 250,000 inhabitants. Slowly, the structure of local government was created to deal with these problems. The 1835 Municipal Corporations Act provided a basic framework for local government, and during the century most towns were given elected councils and the apparatus of local government.

|

| Manchester Town Hall, designed by Alfred Waterhouse (1830–1905), symbolizes the civic pride of the urban civilization created by the Industrial Revolution. The nineteenth century saw the creation of local authorities to deal with the intense problems caused by uncontrolled growth. |

Conditions in the early industrial towns were often cramped, unhealthy, and unsanitary (Figure 3). Rapid expansion meant that families were crowded into cheap lodgings, cellars, and small courts. Piped water supplies and sanitary services were often totally inadequate or non-existent, and resulted in disease and high mortality rates, especially among young children. In 1842, the average life expectancy for children of laboring families in Manchester was 17 years, compared with 38 in rural Rutland. Cholera epidemics in 1831–1883, 1847–1848, and 1865–1866 helped to focus attention upon the need for improvement in sanitary conditions. The first Public Health Act was passed in 1848 and a Board of Health was set up to deal with some of the problems of the industrial towns. But industrialization was not responsible for all the squalor and overcrowding to be found in the towns. Pre-industrial London, for example, had had its unsavory stretches.

Even when new housing was constructed it was often built cheaply by factory owners or speculative builders. Small, terraced houses, often without adequate light or ventilation, with poor foundations and of flimsy construction, soon infested by damp and vermin, created a legacy of slum housing that survived well into the twentieth century in many industrial towns. Indeed it was only after the destruction brought about by the blitz in World War II that extensive rebuilding of nineteenth-century slums in Britain's cities was carried out.

Social concern and planning

Towards the end of the 19th century philanthropists and social reformers, conscious of the destructive physical and social effects of industrialization put forward ideas for limited, planned towns and cities. Robert Owen (1771–1858) had attempted to create a "model" community at New Lanark and the first proper "garden cities" at Letchworth (1903) and Welwyn (1920) show a similar concern for careful regulation of the growth and structure of towns and cities. In 1895–1896 the first industrial estate, at Trafford Park in Manchester, was built; railways, canals and other transport now enabled a separation to be made between work and home, and encouraged a concentration of industry that was socially and economically attractive. On a smaller scale, the houses built by knitting-machine pioneer Jedediah Strutt (1726–1797) can be seen to this day.