Vikings

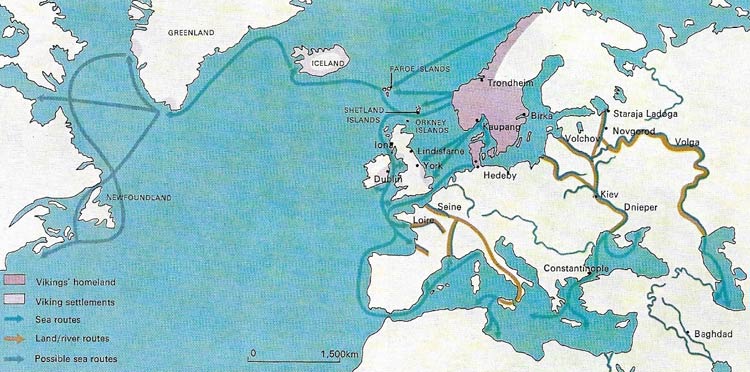

Fig 1. The Scandinavians of the Viking age used these main routes in their search for wealth and land to settle. In the east are the riverside towns they established as centers, such as Kiev and Novgorod. From these, along rivers, the Scandinavians reached the rich trade and wealth of the Orient and the Byzantine Empire. In the west the chief areas settlement were the northern and eastern islands of Britain, northern and eastern England, northern France, and the Irish ports (which they also founded). By the western sea routes they reached America, but failed to establish any settlements there.

Fig 2. This bronze figure of the Buddha was imported from Afghanistan or India to Sweden in the early Viking age, presumably as a souvenir. Other objects imported into Scandinavia and found during excavation include Arabic, Byzantine, English, French, and German coins, as well as silks and foreign animal skins, metalwork from Britain and pottery and glass from northern Germany.

Fig 3. This plan of a house excavated at L'Anse-aux-Meadows in Newfoundland can be dated to the 11th century. It has many of the structural features of houses built by the Vikings in their colonial settlements in Iceland and Greenland.

Fig 4. The hull of a small cargo vessel was raised from the bed of Roskilde fjord in Denmark and reconstructed. It is 13.5 m (44 ft) long. There is decking fore and aft with a hold in the center. The mast is seated on the keel and the one large sail is supported by a single transverse spar. When not in use the spar could be lowered and stowed away. The vessel could also be rowed by means of sweeps inserted through the square holes that are clearly seen in the gunwale plank. Steering was by means of a paddle attached aft on the starboard quarter (starboard being an old Norse word for "steering side").

Fig 5. The open fire in the center of this house, a reconstruction from the town of Hedeby in South Jutland, provided heat for the room and for cooking. The family would sit on the earth benches at the sides of the room and eat off low tables. The walls are of wattle and daub and may have been covered with hangings. There was a room at each end.

Fig 6. The craftsmanship of the Vikings is well demonstrated by this early 11th-century weather vane. Made of gilt bronze, it may originally have graced a Viking ship. The Scandinavians were fascinated by animal ornament. Throughout the Viking age, their craftsmen produced distinguished objects decorated with animal ornament largely free fro the influence of contemporary European art. Objects like this vane demonstrate the brilliance of the ornamentation.

Fig 7. This richly carved ship's prow is part of a complete Viking longship found in a woman's grave of the 9th century at Oseberg in Norway. The ship itself, built of oak, was 23 m (75 ft) long, and was basically a coastal sailing vessel which could also be propelled by oars. One of the larger examples of Viking longships, it was probably used for raiding and longer voyagers of discovery and colonization. Much smaller ships were used for coastal and river warfare and trading. The prow here is decorated with intertwining animals, and is shaped in the form of a serpent, a style that is characteristic of the final pre-Christian period of Viking art.

In the late eighth century the pagan Scandinavians, known as the Vikings, burst upon the rich kingdoms of Western Europe. Improvements in ship design, and overpopulation at home were two reasons behind Viking expansions at this time. They attacked rich and undefended monasteries, pillaging their treasures and killing and enslaving the priests. The attack in 793 on St Cuthbert's monastery at Lindisfarne in Northumberland was the most shocking of these occurrences because it was the first.

|

| These two views from a stone on Lindisfarne commemorate the Viking invasion. An inscription from it reads: "793. In this year dire portents appeared over Northumbria...the ravages of heathen men destroyed God's church on Lindisfarne". |

|

| Thor, the Scandinavian god of thunder agriculture, and war, is usually symbolized by a hammer. In this 6.7 cm (2.5 in) bronze, his beard develops into a hammer. The symbol was often used as an amulet to protect the wearer against evil. |

Colonization of Britain

Some of those who came from Scandinavia turned their attention to colonization. Graves in western Scotland, the Hebrides, Shetland, Orkney and Isle of Man, furnished after the pagan fashions of their Scandinavian homelands with weapons and household goods, tell of the gradual settlement of these areas (Fig 1). In England, raids gave way to settlement in the 860s and, after a series of campaigns against the English kingdoms, the Scandinavians – by treaty with Alfred the Great in 878 – settled as conquerors to the east and north of a line from the River Lea to the Dee. Here they established at least one kingdom (based on York) as well as other political groupings in East Anglia and the Midlands (where their power was based on the "Five Boroughs" – Leicester, Stamford, Lincoln, Derby and Nottingham). By the middle of the tenth century the English had reconquered these areas, although in the early eleventh century the whole of England was again conquered by the Scandinavians, and a Dane, Canute (994–1035), became king of England for a short period.

The Scandinavian settlements in Scotland and the Isle of Man continued until the thirteenth century (in Orkney and Shetland islands until the fifteenth century). The Scandinavians in Ireland did not attempt to conquer the whole country, but founded a series of towns (of which Dublin was the most important) through which they could influence the trade of the Western European seaboard. Goods from France and Spain were exchanged for slaves, furs, ivory and other products of the north.

|

| The annual ceremony at Tynwald on the Isle of Man comes from the assembly established there by the Scandinavians in the Viking age (the Norwegians finally surrendered Man in 1266). Such assemblies acted as a combination of town meeting, law court, and fair, and were held in various places throughout the Viking world. |

In other Western European countries the Scandinavians were less successful as colonists or conquerors. Only in Normandy did they succeed. There in 911 a Scandinavian, Rollo, was given the right to settle and govern much of that corner of France. The Scandinavians also moved into the North Atlantic looking for plunder and farmland. They settled the virtually unknown Faroe Islands and Iceland and reached Greenland, where they founded two major settlements. They also appear to have made landings on the coast of North America.

Eastern Europe

The Scandinavians were also influential in Eastern Europe. From the Roman period onward they traded spasmodically with the eastern Mediterranean, travelling by way of the Polish and Russian rivers. In the eighth century a larger and more organized commercial traffic developed. The Swedes founded trading stations and collected tribute from Finno-Ugric, Balt and Slav tribes in the east Baltic. In the ninth century the Scandinavians contributed to the growth of Russian trading towns at Staraja Ladoga, Novgorod and Kiev. The river route along the Volchov and the Dnieper (which led from Lake Ladoga to the Black Sea and Constantinople, now called Istanbul) was largely con-trolled by the. Scandinavians from the ninth to the eleventh centuries.

Trade and economic organization

The main exports of the Scandinavians were furs, honey and slaves; the main imports silver, spices and other luxury goods. The volume of this eastern trade is demonstrated by the fact that (at a conservative estimate) some 40,000 Arabic coins have been found in Viking age sites in Gotland and Sweden. These eastern adventures are also reflected in long inscriptions carved, in runic characters, on Swedish stones. Some refer to merchant expeditions and imply a fairly peaceful Scandinavian presence in Russia. However some tell of more warlike episodes – a military expedition to Arabia, for example, or of Scandinavian mercenaries in Russia or Byzantium: Greek literary sources attest to the presence of Scandinavians serving in the bodyguard of the emperor.

The raids, colonization, trade and other activities of the Vikings, which have so firmly established them in European history, were based on a settled domestic economy. This economy had its foundation in agriculture but was expanded in the Viking age by the development of marginal land in Scandinavia itself and by the foundation of towns which functioned as major trading stations – towns such as Birka in Sweden and Hedeby in South Jutland. The international contacts of the Scandinavians are clearly seen in these towns, both in excavated material and in the written descriptions of travellers. The Scandinavian of the Viking age was, how-ever, basically a farmer – even traders and pirates were apt to travel extensively abroad, mainly in summer.

The image of the Vikings as marauders and pirates is influenced by the chronicles of priests who identified them with pillaged monasteries. The fact that the Scandinavians were pagan compounded any offence. But in the tenth century the Scandinavians were gradually converted to Christianity and so their image improved.