Wales 1536 to 1914

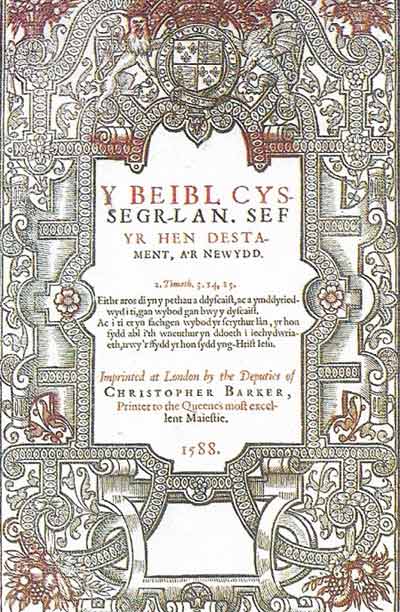

Figure 1. The first Welsh Bible (1588) resulted from a statute in 1563 which ordered that the translation of the Bible into Welsh should be undertaken forthwith. Te work was duly completed by an erudite Denbighshire vicar, William Morgan (c. 1545–1604). The translation provided a literary standard for future generations and ensured that Protestantism would be propagated in the Welsh language.

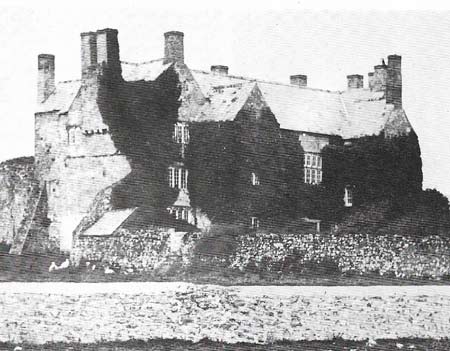

Figure 2. The Sker House, a large, bleak edifice close to the Kenfig Burrows in Glamorgan, is a good example of the many new or remodeled buildings which were constructed by the Welsh gentry in the 16th century. The house was built in a former monastic grange by the Tuberville family. The economic and political power of the gentry at that time was reflected in their imposing country homes.

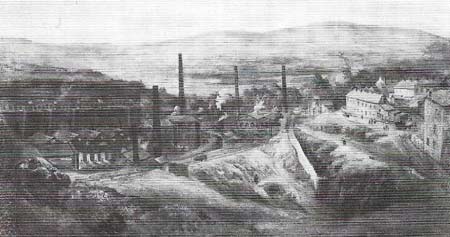

Figure 3. The massive Cyfarthfa ironworks, founded in the mid-18th century, became the focal point of the iron-smelting town of Merthyr. In keeping with much of the Industrial Revolution in Wales, the works were financed by English capital.

Figure 4. The Merthyr riot of 1831 developed from three main causes. First, discontent with the system of compelling workers to spend part of their wages in the expensive company-owned shops; secondly, unemployment and the harsh provisions of the Poor Law; and thirdly unrest at the delay in passing the 1832 Reform Bill.

Figure 5. The Rebecca riots in the early 1840s occurred in separate places across southwest Wales. Disguised as women, small farmers protested against abuses of the turnpike system. They attacked the hated toll gates, burnt haystacks, and threatened local magistrates. A government enquiry in 1844 resolved many of their grievances.

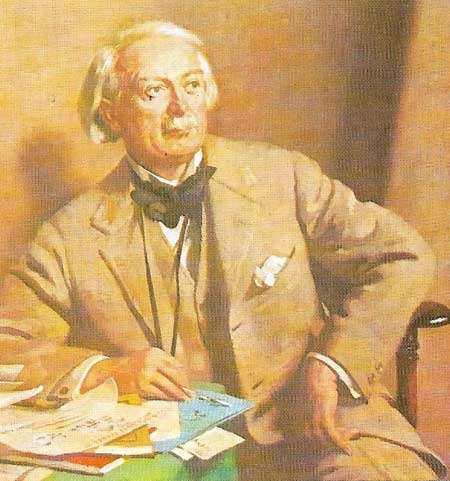

Figure 6. David Lloyd George, MP for Caernarvon boroughs from 1890, made his mark in politics as an enthusiastic champion of the rights of Welshmen, an enemy of privilege and as a "man of the people". As Chancellor of the Exchequer (1908–1915) he introduced crucial social reforms, and his 1909 budget provoked an important constitutional crisis with the Lords. In 1916, he became the first Welshman to be appointed prime minister, which he remained until 1922. He earned a reputation as a courageous and decisive war leader, and a constructive peacemaker after World War I. His fertile mind and oratorical genius aroused widespread devotion and, equally, widespread dislike.

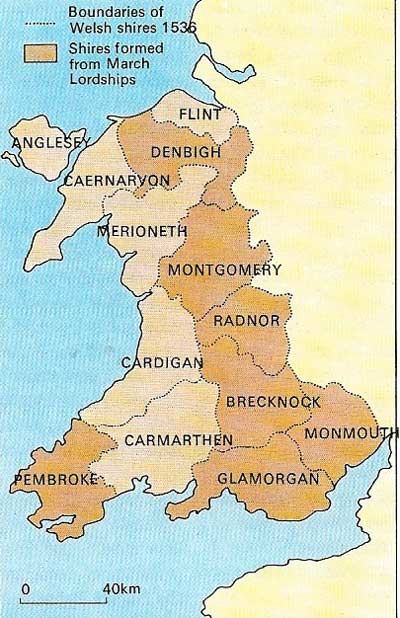

Figure 7. The Acts of Union incorporated Wales into England in order to achieve a more effective governance of Wales and the border area (Marches). Welshmen henceforth were to enjoy the rights and privileges of Englishmen; land was to be inherited according to the practice of primogeniture; and the whole of Wales was divided into shires – a framework that persisted until April 1974. English became the official language of law and government and English common law and methods of local administration were introduced. In return the new Welsh shires and boroughs could send 24 MPs to represent them in the English Parliament.

The Acts of Union (1536–1543) decreed that Wales henceforth was to be governed "in like form" to England. Wales was given a definite administrative boundary and was also unified politically within itself (Figure 7). The most progressive of the Welsh gentry were happy to be subsumed in a common British citizenship and voiced their gratitude to the Tudors for bringing order, stability and prosperity to Wales.

The power of the gentry

The gentry were the most powerful element within society and the task of administering local government remained in their hands for some 350 years. Traditionally conservative, they supported the Crown through every event. During the English Civil Wars (1642–1646, 1648) they fought for the king in order to protect their prosperity and security and, after the Restoration in 1660, they reestablished a monopoly of influence on the society, economy and politics of Wales. Until the mid-19nth century political power lay in the hands of a narrow circle of landowning families, and the mass of society remained deferential to their will. Three developments – the growth of Nonconformism, the Industrial Revolution, and the spread of political radicalism – undermined the foundation of this society.

From the 16th century onwards successive waves of Protestantism lapped over Wales. Much was achieved: Welsh became the language of religion, and the translation of the scriptures into the vernacular (Figure 1) fostered the growth of a Bible-reading public. With the coming of Methodism in the 1730s, Reformation ideas were propagated far more intensively. In 1811, the Methodist movement was forced to sever its connection with the Anglican Church and, in the company of fellow Dissenters, spread widely into rural and industrial areas. Noncomformity became a popular movement so that by 1851 about 80 percent of practicing Christians in Wales were Nonconformists.

|

| Howel Harris (1714-1773) was the moving spirit behind the growth of Welsh Methodism. A fiery evangelist, Harris provided the movement with inspired leadership and an efficient organization. |

The Industrial Revolution in Wales

The second major factor that created modern Wales was the Industrial Revolution. Until the end of the 18th century Wales displayed the main features of a pastoral, preindustrial economy: a primitive technology, a slow rate of technical development and a lack of capital. But the arrival of the Industrial Revolution after 1760 transformed the social and economic life of Wales. Financed largely by English entrepreneurs, industrial development focused on the chain of ironworks on the periphery of the South Wales coalfields and in northeast Wales, on the copper mines of Anglesey and the slate quarries of Caernarvonshire. The spread of canals and railways improved communications and hastened large-scale industrial expansion.

At the same time, population growth began to accelerate dramatically. It rose from 370,000 in 1670 to 586,000 in 1801. Small villages grew into booming towns: in 1801, Merthyr Tydfil, with a population of 7,705, was the largest town in Wales (Figure 3). By 1861, 60 percent of the Welsh people lived in industrial areas. The decline of the iron industry after 1850 was followed by the growth of new steelmaking processes and the massive expansion of the coal industry. As the unparalleled resources of the Rhondda valleys were plundered, coal came to dominate the Welsh economy. By 1912, coal output in the mining valleys of South Wales was more than 50 million tons.

Nationalism and political radicalism

The third factor was the growth of political radicalism, inspired by the revolutionary ideals formulated in France. Many processes hastened these ambitions: the Welsh press created an articulate and informed body of public opinion; acute economic distress in rural and industrial communities encouraged class awareness and a growing interest in political reform; and a slanderous government report – The Treason of the Blue Books in 1847 – injected new life into radicalism and awakened a sense of nationhood. The extension of the franchise in the nineteenth century gave radical Nonconformists the opportunity to undermine the landowning monopoly, to remove religious disabilities, and to create cultural and educational institutions attuned to Welsh circumstances and aspirations. Between 1868 and 1918 Welsh Liberals voiced the ambitions of a new Nonconformist middle and working class, and the response which they evoked from the electorate enabled them to erode the power of the old Anglican squirearchy and to capture the overwhelming majority of parliamentary seats in Wales.

As political nationalism spread in from Europe and Ireland, a new effort was made to emphasize the distinctiveness of Wales and to press for national equality and justice. In Parliament, a ginger-group of young Liberals, led by Thomas Ellis (1859–1889) and David Lloyd George (1863–1945) (Figure 6), called for religious equality, educational opportunity and land reform. Eventually, many gains were achieved: the Church in Wales was disestablished in 1920; Welsh universities, a National Library at Aberystwyth and a National Museum at Cardiff were established; a Welsh department was created within the Board of Education; and the concept of Wales was firmly established. By 1914 it was no longer considered to be a mere geographical term with neither institutions nor pride in its own nationhood.

|

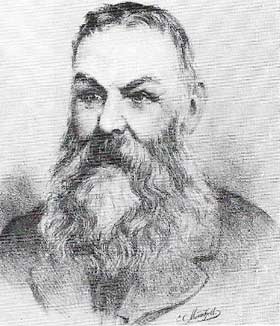

| Michael D. Jones (1822–1898) was one of the principal Welsh nationalists of the 19th century. He strove valiantly to persuade Welshmen to embrace a new, radical philosophy, to agitate for their political rights and to recover their self-respect and confidence. His determination to preserve national identity prompted him to establish a Welsh colony in Patagonia, South America, in 1865; this colony still exists as an isolated Welsh-speaking outpost today. |