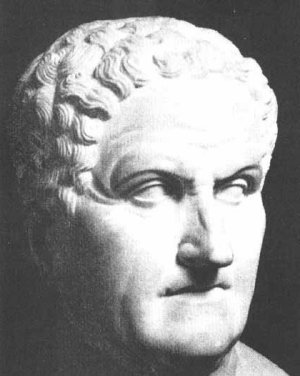

Galen (c. AD 129–c. 216)

Roman surgical instruments.

Galen.

Galen was both an anatomist and a physiologist. He proposed the theory that temperament was controlled by the balance of the four humours in the body (blood, phlegm, and yellow and black bile).

Galen was a Greek physician, born at Pergamus, in Mysia (on the Mediterranean coast of what is now Turkey), who became the most celebrated doctor in the Roman empire. His teachings powerfully influenced the practice of medicine in Europe and the near east for many centuries.

Galen, or Claudius Galenus, began his study of medicine at the age of 19 in Pergamus, before moving on to Smyrna, Corinth, and Alexandria (where there was a famous school of anatomy and surgery). On his return to his native city in AD 158 he was already a celebrated physician and his services were much in demand; he was appointed physician to the school of gladiators which gave him plenty of experience of trauma medicine. But six years later he went to Rome, where he stayed for about four years, and gained such a reputation that he was offered, though he declined, the post of physician to the emperor. Scarcely had he returned to Pergamus, however, when he received a summons from the emperors Marcus Aurelius and L. Verus to attend them in the Venetian territory, and shortly afterwards he followed them to Rome (170). There he remained several years, attending M. Aurelius and his two sons, Commodus and Sextus, and about the end of the 2nd century he was employed by the emperor Severus.

Galen wrote a great deal not only on medical, but also on philosophical subjects, such as logic, ethics, and grammar. His most important anatomical and physiological works are De anatomicis administrationibus, and De usu partium corporis humani. As an anatomist, he combined with patient skill and close observation as practical dissector – not of the human body, but of other animals – accuracy of description and clarity of writing. He gathered up all the medical knowledge of his time and presented it so convincingly that it continued to be, as he left it, the authoritative account of the science for centuries. His ideas about physiology were dominated by theoretical notions that seem strange to us today, notably those of the four Hippocratic elements (hot, cold, wet, and dry) and the Hippocratic humors. His therapeutics were also influenced by the same notions, drugs having the same four elemental qualities as the human body; and he was a believer in the principle of curing diseases traceable, according to him, to the maladmixture of the elements, by the use of drugs having the opposite elementary qualities. In his diagnosis and prognosis he laid great stress on the pulse, on which subject he was perhaps the first and greatest authority, for all subsequent writers adopted his system without alteration. Also he emphasized the doctrine of critical days, which he believed to be influenced by the Moon.

Subsequent Greek and Roman medical writers were mere compilers from his writings; and as soon as his works were translated (in the 9th century) into Arabic they were at once adopted throughout the East to the exclusion of others.

The terms galenical and galenist refer to the controversies of the period when the authority of Galen was strongly asserted against all innovations, and particularly against the introduction of chemical, or rather alchemical, ideas and methods into medicine.

Vitalism

Galen was a proponent of vitalism – a broadly metaphysical doctrine that conceives of a living being as being distinguished from nonliving beings by virtue of some essence that is particular to life and which exists above and beyond the sum of that living being's incarnate parts. Galen held that spirit (pneuma) was the essential principle of life and took three forms – animal spirit (Pneuma physicon), which occurred in the brain; vital spirit (pneuma zoticon), which occurred in the heart; and natural spirit (pneuma physicon), which resided in the liver. Galen's ideas on this remained influential for as long as 1,400 years after his death.

An earlier form of vitalism had been proposed by Aristotle and his works On the Soul and On the Generation of Animals (both c. 350 BC) became canonical vitalist treatises. Aristotle held that the soul (the psyche) is what attributes organizational unity and purposeful activity to a living entity. Later thinkers to offer a more advanced version of the theory included the philosopher and biologist Hans Driesch (1867–1941). Driesch also articulated a philosophy highlighting what he took to be an essential, autonomous, and nonspatial psychoid or mindlike essence behind living things, referring to his experiments with sea urchin embryos, in which separated cells developed into whole organisms.

Galen was responsible for particular conceptual errors that persisted long after him, and vitalism as a theory of life is no longer a part of contemporary biology. Nevertheless, there is no question that both had enormous influence on Western thinking.

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is the practice in medicine of withdrawing blood from patients to prevent or cure illness or disease. While the ancient Egyptians and Greeks were among the first to practice medical bloodletting, it was Galen who produced a systematic bloodletting treatment – a development that would result in much loss of life over the following centuries.

As mentioned above, in accordance with the Hippocratic school of medicine, Galen regarded health as a matter of balancing the four humors – blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Of these, he was particularly interested in blood, which he demonstrated to flow through the arteries of living animals. He believed that illness was often due to a superabundance of blood and therefore recommended bloodletting by venesection (opening a vein by incision or puncture) to remedy it, in part because venesection is a controllable procedure. He offered guidelines about when, where, and how to bleed, depending on the patient's condition and the disease's course. Later methods of bloodletting included blood cupping (cutting the skin and then using heated cups to withdraw the blood by means of suction as they cool) and the use of leeches (especially the species Hirudo medicinalis), for which sucking blood from host mammals is a natural behavior.

Convinced of his findings, Galen eventually completed three books expounding his views on bloodletting. Although Renaissance scholars challenged Galen's authority in many areas, the practice of bloodletting continued, amid increasing controversy, until the end of the 19th century.