Persian Empire of the Achaemenids

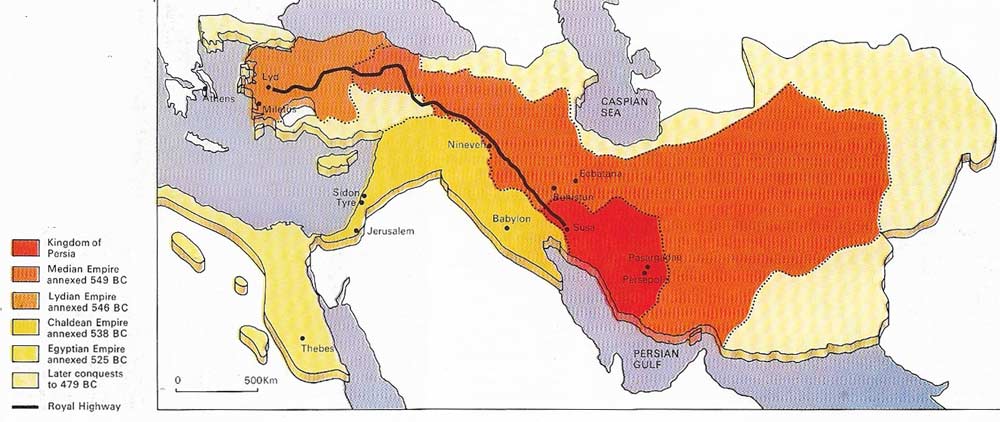

Fig 1. The Persian Empire in the Achaemenid period was administered through satrapies. To maintain contact with these provinces Darius created roads whose combined length was 2,700 km (1,680 miles). At 111 staging posts fresh horses awaited the king's envoys, who could thus traverse the whole system in a week; it took merchant caravans 90 days.

Fig 2. The crushed bowl of Hasanlu, exquisitely made in gold, shows a weather god in a chariot drawn by a bull, and a battle with a monster. It was found in 1958 during excavations of the citadel of Hasanlu at the northern end of the Solduz valley and was clutched in the hands of a man's skeleton. He was probably trying to escape from a palace that collapsed in flames when the citadel was attacked in 800 BC. The bowl is now in the Teheran Museum Treasure Room.

Fig 3. A coin of Xerxes I depicts him in an aggressive pose, but he is best known for leading the Persian forces to defeat at the hands of the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis. Xerxes inherited the empire from his father, Darius I, in 486 BC. In 484 he suppressed a usurper in Egypt in savage fashion and went on to quell a revolt in Babylonia with similar ruthlessness. After early successes in Greece he lost his fleet at Salamis; the Achaemenid decline dates from that period.

Fig 4. The Palace of Persepolis was begun in 518 BC by Darius and was built mainly under Xerxes I in 486–485 BC. It owes much to its situation with its back to the mountain from which the great terrace was partly carved. The magnificent staircases leading to the terrace were wide enough for eight horsemen to ride abreast up the shallow steps. A procession of Immortals carved in stone decorates the sides of the staircases, followed by lines of courtiers – Medes and Persians – and subject peoples bearing tribute. Iron clamps filled with molten lead lock together some of the blocks of stone of which the terrace is built.

Fig 5. The so-called Fire Temple at Naqsh-i-Rustam near Persepolis stands in front of a cliff in which the four tombs of Darius and his successors are carved. It is about 11 m (36 ft) high with blind windows (1) of black limestone and a door (3) leading to an empty room (2). Some authorities believe it to be a Zoroastrian temple for the sacred flame or for holding religious objects.

Fig 6. Persian warriors owed much of their success to their skill with bows. The arrows were carried in a quiver by the bowman (A) who wore leather shoes and cap and bore a short sword. A bodyguard of Darius the Great (B) wore long robes and carried a long spear with a cut-out shield. Such men, known as the Ten Thousand Immortals, were commanded by Darius during the campaign against Egypt and were the mainstay of his military achievements as emperor.

Fig 7. Artaxerxes I (reigned 465–425 BC), a king of the Achaemenid dynasty, is enthroned in the Hall of a Hundred Columns at Persepolis beneath the winged Ahura Mazda, supreme god in the religion of Zoroaster, who was believed to direct the actions of the king as his viceroy, protecting the earth and its ruler.

Fig 8. The tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae commemorates an outstanding leader who united the Medes and Persians to form an empire that played an important intermediary role between the civilizations of East and West. Few kings have left such a reputation for tolerance to subject peoples.

The Persian Empire, during the period of its height, between 550 BC and 480 BC, was the greatest in area and accomplishment the world had then known. Centered on an area comprising much of present-day Iran and Afghanistan it contained 40 million people and gave them common law, systems of coinage, postage and irrigation and a magnificent network of roads (Fig 1), as well as a liberal and unifying religion. Although the power of the Achaemenid dynasty was broken by Alexander the Great in 330 BC Persian influence revived under the Parthian and Sassanid empires and gave way to the Muslim Arab Empire only in the AD 600s.

Persia's early history

Persia is the natural bridge between Europe and Asia. Its history dates back to 6000 BC and the country contains some 250,000 archeological sites (Fig 2), a thousand in the plain before Persepolis (Fig 4) alone. In about 1500 BC nomadic Aryans from the north arrived, giving the country the name Iran or "Land of the Aryans". In 549 BC their descendants, the Medes, were united with the Persians in the south by Cyrus the Great who thus founded the Persian Empire, calling it the Achaemenid Empire after an ancestor.

Cyrus (Fig 8) based his empire not merely on territorial conquest but also on international tolerance and understanding. The rights and religions of all the subject states were upheld and their laws and customs respected. After his victory in Babylon in 539 BC, which ended the Jewish captivity, he ordered the temple in Jerusalem to be rebuilt and more than 40,000 Jews left Babylonia and returned to Palestine. His army added the former realms of Assyria, Lydia and Asia Minor to the Persian Empire, making it the largest political organization of pre-Roman antiquity. The conquests of Cyrus had been carried as far as the Mediterranean in the west and the Hindu Kush in the east when he was slain in battle in 529 BC.

Cyrus was followed by his son Cambyses II (ruled 529–522 BC), who had none of his father's virtues but inherited his occasional vice of cruelty. Cambyses II began his reign by putting to death his brother Smerdis and then, lured by the wealth of Egypt, set out to capture that country. Some 50,000 of his soldiers perished in the campaign and Cambyses unsuccessfully tried to put down the Egyptian religion. In a final outburst he killed his sister and wife Roxana, slew his son Prexaspes and buried 12 of his nobles alive. He died during his return journey to Persia.

The reign of Darius

Darius the Great (548–486 BC), who won a battle for the succession, had been the commander of the Ten Thousand Immortals, the elite of the Persian forces (Fig 6). His succession was marked by revolts among the conquered states, which he rapidly quelled. In Babylon 3,000 leading citizens were crucified. Realizing how vulnerable the vast empire was to any crisis he reduced military control in favor of wise administration and reestablished his realms in a way that became a model of imperial organization. The result was a generation of order and prosperity. Having gained peace and stability at home Darius led his armies first across the Bosporus and the Danube to the Volga, then into the valley of the Indus. The Persian Empire had by that time achieved its greatest extent and influence.

|

| Depicted in color on enameled brickwork from the palace of Susa, one of the two capitals of the empire of Darius, is a soldier of the Ten Thousand Immortals holding a spear and carrying his bow and quiver. Darius rewarded his loyal bodyguard by having them portrayed on the walls of each palace he built. |

Agriculture based on both grain and livestock was the mainstay of the country. Artificial irrigation was introduced by means of tunnels many miles long.

The original religion of the country had been the worship of Mithras, identified with the sun, and of Anahita, goddess of water and fertility. This religion was later combined with the worship of a supreme being, Ahura Mazda (Fig 7), "the Wise Lord" of the sixth-century prophet Zoroaster, or Zarathustra. As creator and ruler of the world Ahura Mazda clothed himself with the firmament, the sun and moon were his eyes and all forms of nature were his: earth, fire (Fig 5), wind and water. To avoid polluting these natural elements Parsees (who still follow Zoroastrian beliefs in India) expose their dead on "towers of silence" to be devoured by vultures.

|

| Underground water tunnels, called ghanats, first introduced to Persia in Achaemenid times, carry mountain water across relies of desert safe from evaporation that would deplete surface canals. A one-man windlass is used to reach the tunnels through shafts sunk at intervals of some 10 m (30 ft). A digger must work alone in a tunnel only 40 by 60 cm (2 by 3 ft) in height and width, keeping the channel straight and accurately gauging the amount of fall needed to enable the water to flow steadily to its point of use. These unique water systems contributed as much to the progress of the Persian Empire as the wisdom of its rulers. |

The invasion of Greece

Persia's monarchical form of government was supported by her people who believed that the sovereignty of individuals was best maintained by an individual sovereign, the "King of Kings". On the other hand the city-state of Athens propounded the idea of democracy, except for slaves and non-citizens. Darius considered the Greek city-states and their colonies a danger, and when Ionia revolted and received aid from Sparta and Athens, he crossed the Aegean but was defeated by an Athenian force at Marathon. In the midst of preparations for another attack upon Greece he died in 486 BC.

Xerxes (c. 519–465 BC), son of Darius, crossed the Hellespont with a vast army and defeated the Spartans at Thermopylae. But he was driven out of Europe in 479 BC after incurring the lasting hatred of the Greeks by burning the Acropolis at Athens. The Achaemenid Empire then declined until Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) from Macedon defeated the last of the dynasty, Darius III, at the Battle of Arbela (also called the Battle of Gaugamela) in 331 BC. He routed a huge Persian army and burnt Persepolis, possibly to avenge the destruction of the Acropolis. Thereafter, Persia formed part of the empire of Alexander.