surgery through the ages

Figure 1. Galen.

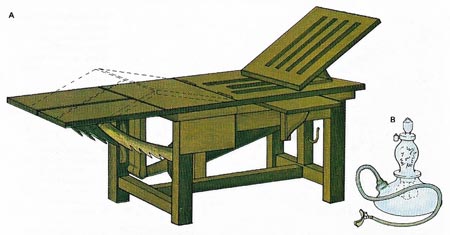

Figure 2. Roman surgical instruments.

Figure 3. The first purpose-built operating tables (A) appeared in the 19th century. They were cumbersome but basically the same as modern ones. The ether inhaler (B) replaced whisky or rum as a painkiller.

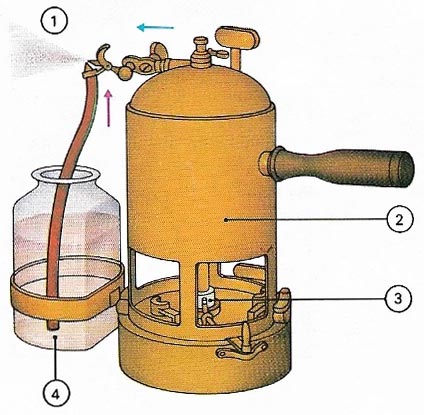

Figure 4. The discovery by Pasteur that germs cause infection led to Joseph Lister's introduction of antisepsis – the treatment of wounds with carbolic acid (phenol0. Lister first introduced a hand-operated spray, then a steam model. The steam (1) from the boiler (2) – heated by methylated spirit on a wick (3) – sucked carbolic acid vapor from a jar (4) thus filing the air with an antiseptic mist.

Surgery, which is the branch of medicine concerned with manual treatment of injuries and disorders, has been practiced for many centuries but only since the 19th century has it been regarded as anything more than an inferior branch of the medical profession. The "physicians" with their charms and potions were the important people of early medicine.

Surgery in ancient times

Excavations at the ancient city of Ur have yielded various bronze knives believed to have been surgical instruments. Archeologists have discovered several stone-age and bronze-age skulls with neat round holes in them. These holes were made while the patient was alive for there is evidence of healing.

The Greeks knew a great deal about surgery – the two most important figures being Aesculapius and Hippocrates. The Romans, too, had their surgeons – notably Galen (originally a Greek) (Figure 1). Much of their work was concerned with injuries received in the gladiators' arena. Galen distinguished between muscles, nerves, and tendons, and devised techniques for joining broken tendons. He even repaired injuries to the intestine and removed tonsils. Many supposed surgical instruments have been found in the ruins of Pompeii, most are of bronze but some are made of steel (Figure 2).

Surgery in the Middle Ages

Unfortunately, surgery did not progress any further for many centuries. There are records of various operations for the removal of growths and stones but little new knowledge was gained. One of the first illustrated works on surgery was produced by an Arab named Albucasis who lived from 936 to 1013 AD. It dealt with instruments, operations for the removal of stones (e.g., from the bladder) and with the treatment of fractures and dislocations. Throughout the Middle Ages surgeons had a great deal of experience of battle wounds and their treatment but no general advance could be made because it was illegal to dissect bodies. Surgeons could not therefore improve their knowledge to any great extent.

One of the great surgeons of this time was Guy de Chauliac (1300–1367), a Frenchman. His book called Chirurgia Magna became a standard work when it was eventually printed in 1478. He encouraged the use of trusses for the cure of hernia although he also developed an operating technique for this condition. Chauliac is believed to have been the first person to treat fractures with tension methods (i.e., using heavy weights attached to ropes to keep the limbs straight and stretched). He was also responsible for hanging a rope over his patients to enable them to move more easily. Chauliac stressed the importance of anatomical knowledge in surgery.

The invention of gunpowder brought about far more extensive and serious wounding and this had a profound influence on surgery. More and more became known about the body and how to treat various types of wound. The Renaissance in Europe led to a revival of the study of anatomy and, with it, the further growth of surgery. Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) was one of the great surgeons of this period. He was in the army and did a great deal of work on wounded men. He devised new ways of dressing wounds and also replaced cauterizing (i.e. burning) with ligaturing (tying) for stopping bleeding. He even devised artificial limbs.

Advances in anatomy and surgery

During the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, anatomical knowledge increased enormously. William Harvey demonstrated the function of the heart and the circulation of the blood and Marcello Malpighi showed how blood was conveyed from artery to vein by means of numerous tiny capillaries. Two important surgeons of the eighteenth century were William Cheselden and John Hunter. The former made his name with operations for the removal of stones in the bladder but was also a good general surgeon and teacher. John Hunter was an experimenter as well as a surgeon. As a result of an experiment on a deer he learned that if an artery is tied, smaller arteries may grow and take over the functions of the main one. His first human patient to undergo such an operation had a tumor in an artery of the knee – a condition that formerly required amputation. The result was a complete success.

In spite of all these advances in the study of anatomy and surgical technique, operations were limited by the agony and pain caused to the patient, for there were no anesthetics in those days. Surgeons were not judged by their skill but by their speed, and the best were able to amputate a leg in under a minute. In 1800 the Royal College of Surgeons was founded and surgery was lifted to a higher plane in the field of medicine. Large hospitals were already in existence and the teaching of anatomy was increasing.

The rise of anesthetics

In 1799 Humphrey Davy discovered that nitrous oxide (laughing gas) could alleviate pain and he suggested that it might be useful in dentistry. It was some years, however, before an American doctor named Wells used it for the first painless extraction (1844). Used alone, however, nitrous oxide is not suitable and other compounds were soon tried. Ether and chloroform were widely used.

The first operation under ether was performed in the United States in 1946, and in the same year Robert Liston carried out an amputation on a patient under ether in London. James Simpson, an Edinburgh surgeon and Professor of Midwifery decided that ether was unsuitable for midwifery and sought to find another substance. He found it in chloroform, which he began to use in the face of religious opposition. The opposition, however, ceased when he successfully treated Queen Victoria at the birth of Prince Leopold.

From these simple beginnings the study of anesthetics grew until at the present day there are a great many in use. The new compounds lack, in general, the unpleasant after-effects and are less dangerous. Many can be administered by a simple injection and they completely relax all muscles. This factor is very important as the "muscle twitches" of patients were very disturbing for the early surgeons.

The advent of anesthetics cleared the way for many more intricate operations needing longer times to perform. This was not the end of the surgeon's problems, however. About half of the operations ended fatally for the patients. To open the body cavity meant almost certain death. This was not due to bad surgery or nursing but to subsequent infection of the wound. Even such distinguished surgeons as Robert Liston and James Syme lost many of their patients in this way. Surgical wards stank of gangrene and decay, and pus was regarded as a necessary part of healing. Although even some Greek surgeons had advised washing the hands before dealing with patients, this aspect was overlooked and the doctors strode around in blood-stained coats. The bloodier the coat, the higher the reputation of the surgeon.

Antiseptic surgery

For ridding us of the scourge of sepsis (infection by germs), we have to thank Joseph Lister, a very careful and distinguished surgeon. He was appalled by the loss of life in surgical wards after even minor operations and set about finding the cause. Having been informed of Pasteur's work on fermentation, Lister deduced that wound infection and putrefaction was also due to airborne microbes. We now know of course that he was right. He sought something to destroy the germs and for a long while he used carbolic acid preparations (Figure 4). He treated the wound, the dressings and everything else with carbolic to kill the germs. This antiseptic system (against germs) is now replaced by the aseptic system (without germs) where everything used in the theater is sterile. It was Lister who must take the credit, however, for showing how sepsis could be avoided.

The stage was no set for further advances in the art of surgery and the scope of operations. Lister had demonstrated the success of his methods and conservative surgery (i.e. saving instead of amputating limbs) increased. The body cavity and internal organs, even the brain, were now open to surgery with little risk and new techniques and instruments continued to appear. Blood transfusion and the discovery of antibiotics have greatly aided the surgeon and very long operations are safely carried out every day. The second World War saw several spectacular advances in the treatment of wounds – notably with antibiotics and plastic surgery.