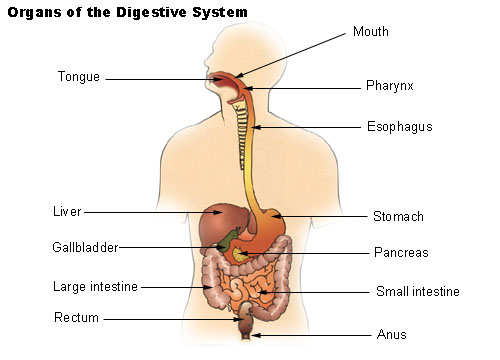

digestive system

Figure 1. Organs of the digestive system.

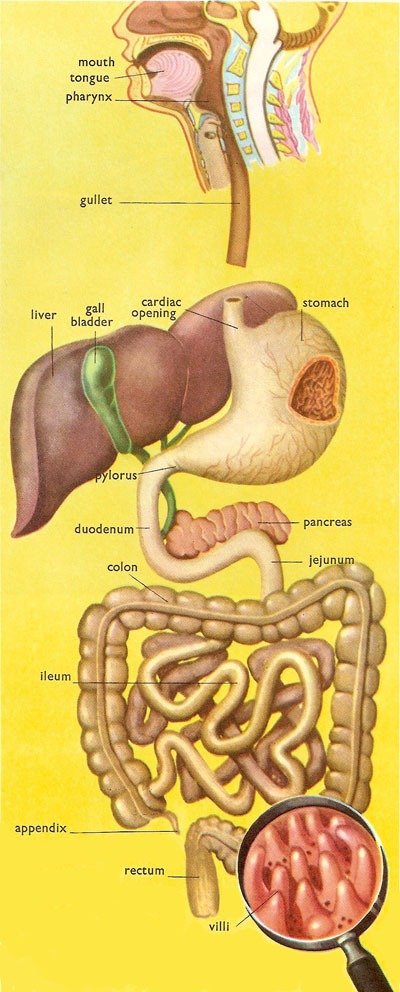

Figure 2. The digestive system: overall view

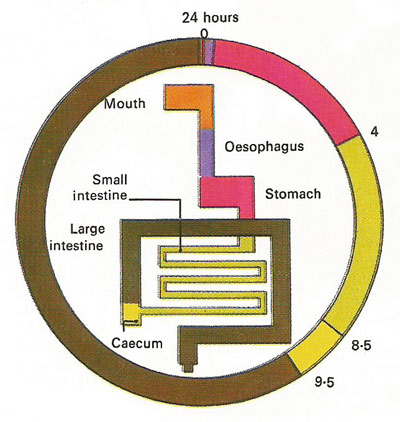

Figure 3. A typical time scale for the passage of food through the digestive tract relates each part of the system to the time on the clock. Correct timing is essential for two reasons: food must stay in the stomach and small intestine long enough to allow complete breakdown of protein, fat, and carbohydrate; and the residue must pass through the large intestine slowly enough to allow water to be reabsorbed into the body.

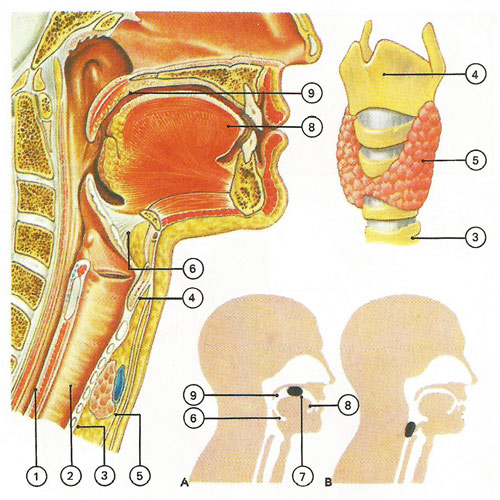

Figure 4. The mouth is a gateway not only to the digestive system but also to the respiratory system. The esophagus (1) lies behind the trachea (2) which is supported by cartilage rings (3). The larynx is at the top of the trachea and its front is formed by the thyroid cartilage (4), so called because of its proximity to the thyroid gland ((5). The flap-like epiglottis (6) is attached to this cartilage. Food, mixed with saliva, is formed into a bolus (7) and pushed by the tongue (8) into the pharynx. During swallowing (A, B) the soft palate (9) blocks entry to the nose and the epiglottis closes.

The digestive system is the organ system that includes the gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) and its accessory organs. The digestive system processes food into molecules that can be absorbed and utilized by the cells of the body. Food is broken down, bit by bit, until the molecules are small enough to be absorbed and the waste products are eliminated. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract, also called the digestive tract, alimentary canal, or gut, consists of a long continuous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. It includes the following regions:

The tongue and teeth are accessory structures located in the mouth. The salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are major accessory organs that have a role in digestion. These organs secrete fluids into the GI tract.

Food undergoes three types of processes in the body:

Digestion and absorption occur in the GI tract. After the nutrients are absorbed, they are available to all cells in the body and are utilized by the body cells in metabolism.

Anatomy

The mouth contains the tongue which is covered with tiny projecting papillae through which are conveyed sensations of taste and touch; the teeth, 32 in number of which 8 are called incisors, 4 canines, 8 premolars, and 12 molars; and the salivary glands, which secrete saliva.

The process of digestion starts in the mouth. Food is masticated (chewed) by the teeth, moistened by the saliva, which contains important chemical substances for changing it, and rolled by the tongue. It is then pushed backward by the tongue into

The pharynx, a funnel-shaped opening which is the continuation of the mouth. The food then passes down

The esophagus, or gullet. This is a very elastic, muscular tube about eight to ten inches (18 to 25 centimeters) long. The food is forced onward by the involuntary contractions of the muscles in the esophagus. It passes from the esophagus into the stomach.

The cardiac opening or orifice relaxes to allow the food to pass through, and then closes again.

The stomach can hold about a liter. It is made up of layers of muscular fibers which contract and churn the food, breaking it up still further. The inner layer of the stomach contains numerous glands. These secrete gastric juice, which carries on the process of digestion begun in the mouth by the saliva. About half-an-hour after food has been eaten, the stomach begins to discharge its contents, now reduced to a thin, gruel-like liquid (chyme) through

The pylorus, the exit of the stomach, consisting of a band of muscular fibers which relaxes from time to time to allow food to pass into the

The small intestine, the first part of the intestinal tube through which food passes on leaving the stomach. It is about 20 to 22 feet (6.1 to 6.7 meters) long and about 1½ to 2 inches (3.8 to 5.1 centimeters) in diameter at first, narrowing slightly toward its lower end. It is made up of three parts: the upper part, known as the duodenum, is about 11 inches (28 centimeters) long, and receives the juices of the two most important glands of the digestive system, the liver and the pancreas. These convert the food still further so that it is in a state in which it can be absorbed by the body. The middle part of the small intestine is known as the jejunum (for the Latin for "empty" because food is seldom found in it after death). It is about 8 to 9 feet (2.4 to 2.7 meters) long. After passing through this the food goes on to the longest and most coiled or twisted part of the intestine, known as the ileum, about 12 feet (3.7 meters) long. Its wall is covered by about 5 million tiny projections resembling hairs called villi. These absorb the nourishment from the food.

The liver is the largest gland of the human body, with a weight of about 3 to 3½ pounds (1.4 to 1.6 kilograms). It secretes bile, a greenish, bitter juice which breaks up the fatty part of the food into tiny drops. Bile from the liver is collected in the gall-bladder from which it flows into the intestine.

The pancreas is a small gland which secretes pancreatic juice. This plays an important part in the chemical change of food. The food then passes to

The large intestine which is about 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 meters) long, and which consists of the cecum, the colon, and the rectum. In the colon most of the water is absorbed from the food residues. The semisolid feces which remain pass through the rectum and out of the body.

Functions

The digestive system prepares nutrients for utilization by body cells through six activities, or functions.

Ingestion

The first activity of the digestive system is to take in food through the mouth. This process, called ingestion, has to take place before anything else can happen.

Mechanical digestion

The large pieces of food that are ingested have to be broken into smaller particles that can be acted upon by various enzymes. This is mechanical digestion, which begins in the mouth with chewing or mastication and continues with churning and mixing actions in the stomach.

Chemical digestion

The complex molecules of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are transformed by chemical digestion into smaller molecules that can be absorbed and utilized by the cells. Chemical digestion, through a process called hydrolysis, uses water and digestive enzymes to break down the complex molecules. Digestive enzymes speed up the hydrolysis process, which is otherwise very slow.

Movements

After ingestion and mastication, the food particles move from the mouth into the pharynx, then into the esophagus. This movement is deglutition, or swallowing. Mixing movements occur in the stomach as a result of smooth muscle contraction. These repetitive contractions usually occur in small segments of the GI tract and mix the food particles with enzymes and other fluids. The movements that propel the food particles through the GI tract are called peristalsis. These are rhythmic waves of contractions that move the food particles through the various regions in which mechanical and chemical digestion takes place.

Absorption

The simple molecules that result from chemical digestion pass through cell membranes of the lining in the small intestine into the blood or lymph capillaries. This process is called absorption.

Elimination

The food molecules that cannot be digested or absorbed need to be eliminated from the body. The removal of indigestible wastes through the anus, in the form of feces, is defecation or elimination.

General structure

The long continuous tube that is the GI tract is about 9 m in length. It opens to the outside at both ends, through the mouth at one end and through the anus at the other. Although there are variations in each region, the basic structure of the wall is the same throughout the entire length of the tube.

The wall of the GI tract has four layers or tunics:

The mucosa, or mucous membrane layer, is the innermost tunic of the wall. It lines the lumen of the GI tract. The mucosa consists of epithelium, an underlying loose connective tissue layer called lamina propria, and a thin layer of smooth muscle called the muscularis mucosa. In certain regions, the mucosa develops folds that increase the surface area. Certain cells in the mucosa secrete mucus, digestive enzymes, and hormones. Ducts from other glands pass through the mucosa to the lumen. In the mouth and anus, where thickness for protection against abrasion is needed, the epithelium is stratified squamous tissue. The stomach and intestines have a thin simple columnar epithelial layer for secretion and absorption.

The submucosa is a thick layer of loose connective tissue that surrounds the mucosa. This layer also contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves. Glands may be embedded in this layer.

The smooth muscle responsible for movements of the GI tract is arranged in two layers, an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. The myenteric plexus is between the two muscle layers.

Above the diaphragm, the outermost layer of the GI tract is a connective tissue called adventitia. Below the diaphragm, it is called serosa.

Movement of food through the system

The large, hollow organs of the digestive tract contain a layer of muscle that enables their walls to move. The movement of organ walls can propel food and liquid through the system and also can mix the contents within each organ. Food moves from one organ to the next through muscle action called peristalsis. Peristalsis looks like an ocean wave traveling through the muscle. The muscle of the organ contracts to create a narrowing and then propels the narrowed portion slowly down the length of the organ. These waves of narrowing push the food and fluid in front of them through each hollow organ.

The first major muscle movement occurs when food or liquid is swallowed. Although you are able to start swallowing by choice, once the swallow begins, it becomes involuntary and proceeds under the control of the nerves.

Swallowed food is pushed into the esophagus, which connects the throat above with the stomach below. At the junction of the esophagus and stomach, there is a ringlike muscle, called the lower esophageal sphincter, closing the passage between the two organs. As food approaches the closed sphincter, the sphincter relaxes and allows the food to pass through to the stomach.

The stomach has three mechanical tasks. First, it stores the swallowed food and liquid. To do this, the muscle of the upper part of the stomach relaxes to accept large volumes of swallowed material. The second job is to mix up the food, liquid, and digestive juice produced by the stomach. The lower part of the stomach mixes these materials by its muscle action. The third task of the stomach is to empty its contents slowly into the small intestine.

Several factors affect emptying of the stomach, including the kind of food and the degree of muscle action of the emptying stomach and the small intestine. Carbohydrates, for example, spend the least amount of time in the stomach, while protein stays in the stomach longer, and fats the longest. As the food dissolves into the juices from the pancreas, liver, and intestine, the contents of the intestine are mixed and pushed forward to allow further digestion.

Finally, the digested nutrients are absorbed through the intestinal walls and transported throughout the body. The waste products of this process include undigested parts of the food, known as fiber, and older cells that have been shed from the mucosa. These materials are pushed into the colon, where they remain until the feces are expelled by a bowel movement.

Production of digestive juices

The digestive glands that act first are in the mouth – the salivary glands. Saliva produced by these glands contains an enzyme that begins to digest the starch from food into smaller molecules. An enzyme is a substance that speeds up chemical reactions in the body.

The next set of digestive glands is in the stomach lining. They produce stomach acid and an enzyme that digests protein. A thick mucus layer coats the mucosa and helps keep the acidic digestive juice from dissolving the tissue of the stomach itself. In most people, the stomach mucosa is able to resist the juice, although food and other tissues of the body cannot.

After the stomach empties the food and juice mixture into the small intestine, the juices of two other digestive organs mix with the food. One of these organs, the pancreas, produces a juice that contains a wide array of enzymes to break down the carbohydrate, fat, and protein in food. Other enzymes that are active in the process come from glands in the wall of the intestine.

The second organ, the liver, produces yet another digestive juice – bile. Bile is stored between meals in the gallbladder. At mealtime, it is squeezed out of the gallbladder, through the bile ducts, and into the intestine to mix with the fat in food. The bile acids dissolve fat into the watery contents of the intestine, much like detergents that dissolve grease from a frying pan. After fat is dissolved, it is digested by enzymes from the pancreas and the lining of the intestine.

Absorption and transport of nutrients

Most digested molecules of food, as well as water and minerals, are absorbed through the small intestine. The mucosa of the small intestine contains many folds that are covered with tiny fingerlike projections called villi. In turn, the villi are covered with microscopic projections called microvilli. These structures create a vast surface area through which nutrients can be absorbed. Specialized cells allow absorbed materials to cross the mucosa into the blood, where they are carried off in the bloodstream to other parts of the body for storage or further chemical change. This part of the process varies with different types of nutrients.

Carbohydrates

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 recommend that 45 to 65 percent of total daily calories be from carbohydrates. Foods rich in carbohydrates include bread, potatoes, dried peas and beans, rice, pasta, fruits, and vegetables. Many of these foods contain both starch and fiber.

The digestible carbohydrates – starch and sugar – are broken into simpler molecules by enzymes in the saliva, in juice produced by the pancreas, and in the lining of the small intestine. Starch is digested in two steps. First, an enzyme in the saliva and pancreatic juice breaks the starch into molecules called maltose. Then an enzyme in the lining of the small intestine splits the maltose into glucose molecules that can be absorbed into the blood. Glucose is carried through the bloodstream to the liver, where it is stored or used to provide energy for the work of the body.

Sugars

Sugars are digested in one step. An enzyme in the lining of the small intestine digests sucrose, also known as table sugar, into glucose and fructose, which are absorbed through the intestine into the blood. Milk contains another type of sugar, lactose, which is changed into absorbable molecules by another enzyme in the intestinal lining.

Fiber

Fiber is indigestible and moves through the digestive tract without being broken down by enzymes. Many foods contain both soluble and insoluble fiber. Soluble fiber dissolves easily in water and takes on a soft, gel-like texture in the intestines. Insoluble fiber, on the other hand, passes essentially unchanged through the intestines.

Protein

Foods such as meat, eggs, and beans consist of giant molecules of protein that must be digested by enzymes before they can be used to build and repair body tissues. An enzyme in the juice of the stomach starts the digestion of swallowed protein. Then in the small intestine, several enzymes from the pancreatic juice and the lining of the intestine complete the breakdown of huge protein molecules into small molecules called amino acids. These small molecules can be absorbed through the small intestine into the blood and then be carried to all parts of the body to build the walls and other parts of cells.

Fats

Fat molecules are a rich source of energy for the body. The first step in digestion of a fat such as butter is to dissolve it into the watery content of the intestine. The bile acids produced by the liver dissolve fat into tiny droplets and allow pancreatic and intestinal enzymes to break the large fat molecules into smaller ones. Some of these small molecules are fatty acids and cholesterol. The bile acids combine with the fatty acids and cholesterol and help these molecules move into the cells of the mucosa. In these cells the small molecules are formed back into large ones, most of which pass into vessels called lymphatics near the intestine. These small vessels carry the reformed fat to the veins of the chest, and the blood carries the fat to storage deposits in different parts of the body.

Vitamins

Another vital part of food that is absorbed through the small intestine are vitamins. The two types of vitamins are classified by the fluid in which they can be dissolved: water-soluble vitamins (all the B vitamins and vitamin C) and fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E, and K). Fat-soluble vitamins are stored in the liver and fatty tissue of the body, whereas water-soluble vitamins are not easily stored and excess amounts are flushed out in the urine.

Water and salt

Most of the material absorbed through the small intestine is water in which salt is dissolved. The salt and water come from the food and liquid you swallow and the juices secreted by the many digestive glands.

Control of the digestive process

Hormone regulators

The major hormones that control the functions of the digestive system are produced and released by cells in the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine. These hormones are released into the blood of the digestive tract, travel back to the heart and through the arteries, and return to the digestive system where they stimulate digestive juices and cause organ movement.

The main hormones that control digestion are gastrin, secretin, and cholecystokinin (CCK):

Additional hormones in the digestive system regulate appetite:

Both of these hormones work on the brain to help regulate the intake of food for energy. Researchers are studying other hormones that may play a part in inhibiting appetite, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GPL-1), oxyntomodulin, and pancreatic polypeptide.

Nerve regulators

Two types of nerves help control the action of the digestive system.

Extrinsic, or outside, nerves come to the digestive organs from the brain or the spinal cord. They release two chemicals, acetylcholine and adrenaline. Acetylcholine causes the muscle layer of the digestive organs to squeeze with more force and increase the "push" of food and juice through the digestive tract. It also causes the stomach and pancreas to produce more digestive juice. Adrenaline has the opposite effect. It relaxes the muscle of the stomach and intestine and decreases the flow of blood to these organs, slowing or stopping digestion.

The intrinsic, or inside, nerves make up a very dense network embedded in the walls of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon. The intrinsic nerves are triggered to act when the walls of the hollow organs are stretched by food. They release many different substances that speed up or delay the movement of food and the production of juices by the digestive organs.

Together, nerves, hormones, the blood, and the organs of the digestive system conduct the complex tasks of digesting and absorbing nutrients from the foods and liquids you consume each day.